- Civil Rights

State-Based Civil Rights Enforcement to Fill the Federal Vacuum

By Catherine E. Lhamon, Executive Director of the Edley Center on Law & Democracy, UC Berkeley

Katy Joseph, Senior Fellow at the Edley Center on Law & Democracy, UC Berkeley

The idea

At a crucible moment in American history, after the nation witnessed firehoses wielded against children seeking justice, a governor blocking a schoolhouse door, and brutal beatings of Black Americans asking to be treated with dignity, this nation came together to agree on a federal backstop against identity-based discrimination against individuals. Civil rights leaders pleaded with the federal government to stop abuses at the state level of Black people simply because they were Black. And President Kennedy recognized that this country had no systematic way for a president to ensure a minimum threshold for the treatment of our nation’s people. In 1964, a bipartisan Congress enacted the 1964 Civil Rights Act with specific requirements for when and how the federal government might address discrimination. Crucially, the new law imposed the simple requirement that no federal funds could be spent to discriminate on the basis of race, color, or national origin.1 Since then, bipartisan coalitions in Congress have added further civil rights protections, signed into law by presidents of both parties. And as beautiful as these guarantees are, their signal defect has been precisely what led to their creation: they are federal. Only.

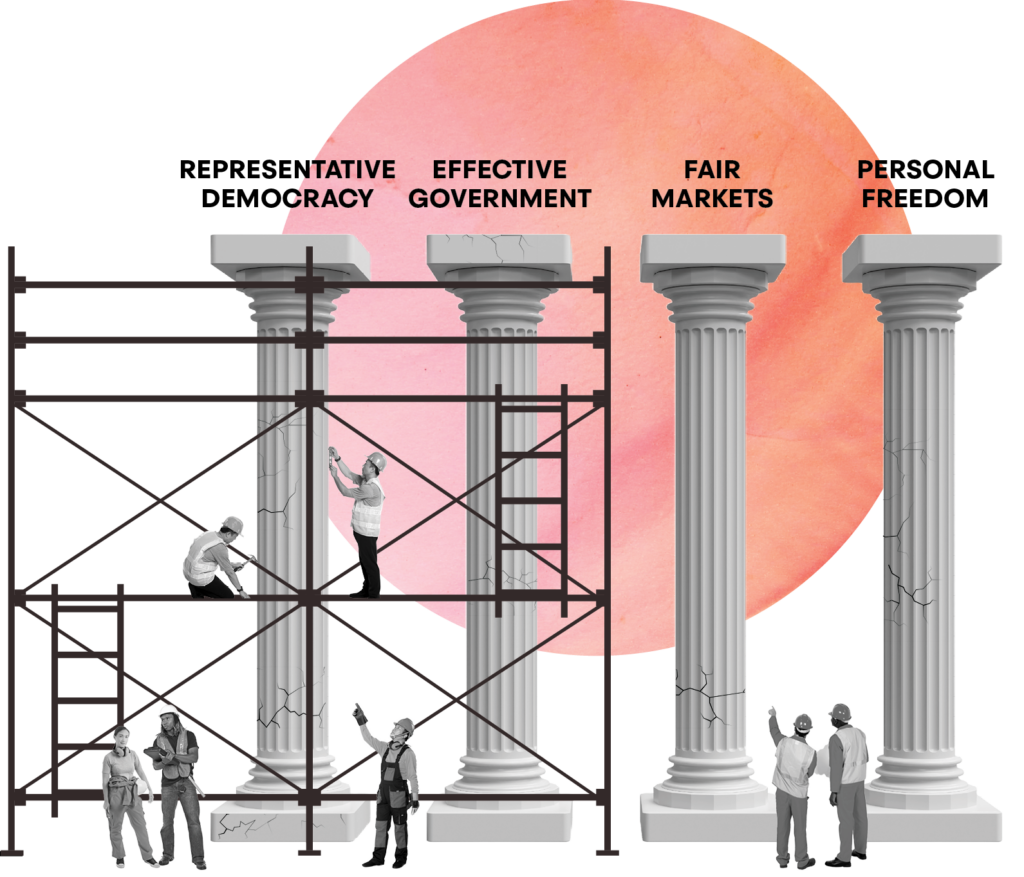

The truths shared in our founding documents may be self-evident but they are not self-executing. In fact, some of the most important tools to achieve them were added to the Constitution only after the Civil War—and more than a half century after it ended. As monumental as the passage of federal civil rights laws were in that evolution, an overreliance on the federal government has led many states to neglect the need for a robust rights safety net that supplements, supports, and updates these federal protections. The resulting gap means that state lawmakers now have a timely opportunity to build a civil rights infrastructure that is resilient and worthy of the democracy we strive to be.

The urgency of this moment is plain. Today’s federal government expresses disdain for the principle that all people deserve equal treatment under the law.2

Los Angeles, CA, 2025. (Photo by SAHAB ZARIBAF/Middle East Images/AFP via Getty Images)

In the current climate, some states are acting in the wrong direction, taking steps to roll back protections that once provided a safety net. Iowa recently enacted the first state law ever to remove an existing basis for protection, rescinding civil rights safeguards based on gender identity.3 And Tennessee moved to transfer civil rights enforcement from its independent human rights commission to its attorney general’s office, making enforcement entirely political and subject to influence by elected officials.4 These developments, combined with the absence of even a veneer of a federal backstop against discrimination, reveal the fragility of protections that the federal structure gave us the luxury to take for granted.

But states can create new possibilities. Meaningful civil rights infrastructure at the state level includes comprehensive nondiscrimination protections, enshrined into law, as well as a functioning and transparent enforcement apparatus in each state. Today, states vary in both the legal protections they promise as well as in the enforcement structures they have in place. What is true across all states is that none have been built in the context of complete federal withdrawal from the business of protecting individuals. States effectively ceded their responsibility to the federal government, undermining their own capacity to fulfill a vision that states should supplement the minimal threshold that the federal government is now not even trying to provide. Ceding that protective responsibility was never good for people or for government; now is the time to correct prior missteps to build a meaningful state and local civil rights infrastructure that works.

The work ahead is substantial, but so is what hangs in the balance: the promise of a government that responds to all its people, translating rights on paper into justice in practice. Whatever a state’s starting point, there are clear actions to be taken to protect and advance our nation’s longstanding aspiration of equality under the law for all.

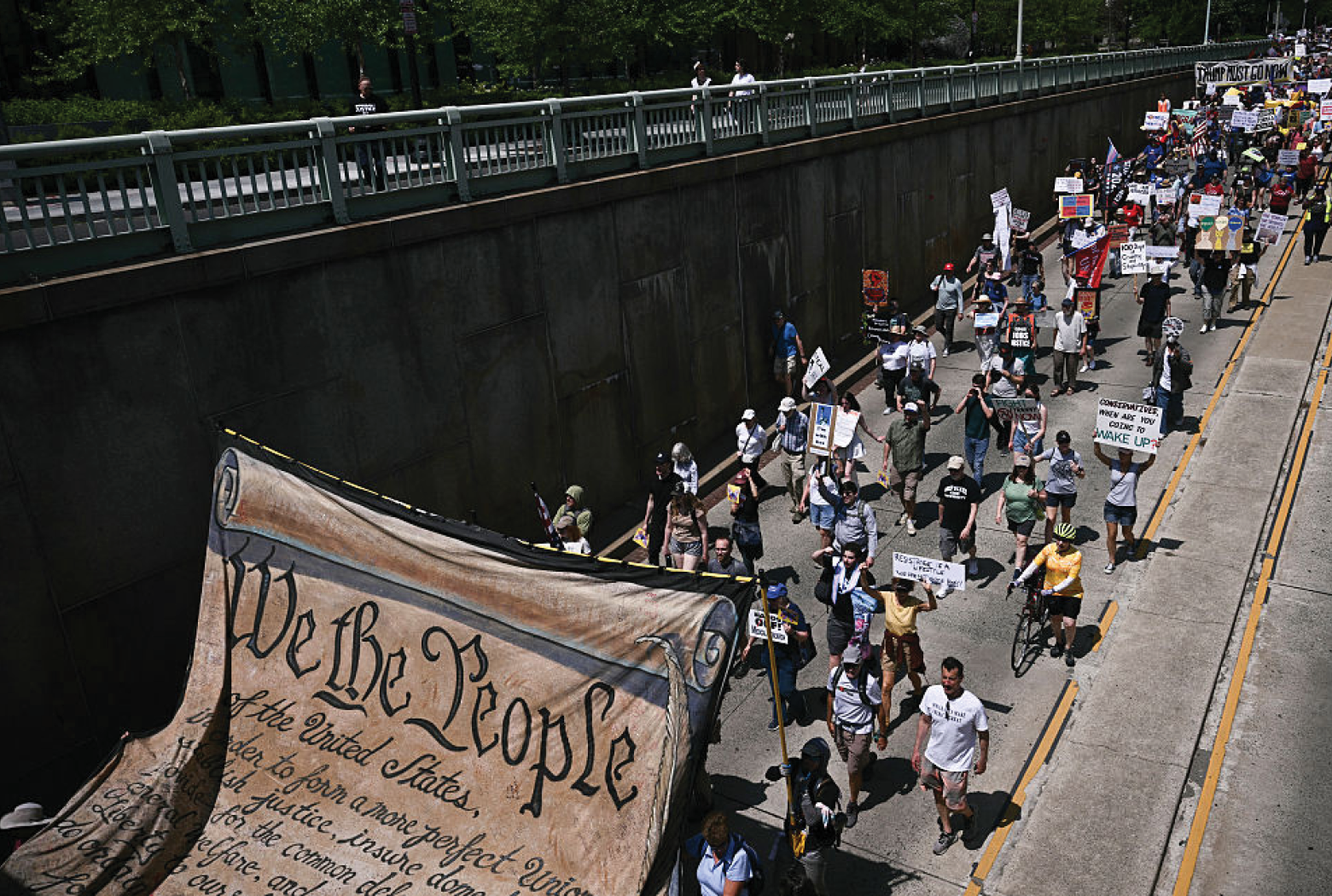

Washington, DC, 2025. (Photo by BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

A few exemplar states have taken some, though not enough, action, reproducing the very patchwork of protections that federal lawmakers sought to remedy over the past 60 years. But these state actions to date offer some models for what should, and could, be done now.

Case studies

Maryland

Maryland stands as a recent and powerful example of advancement of state civil rights protection capacity, representing both an example of a state stepping into the gap left by the federal government, as well as a new framework for how to enforce protections. Senate Bill 540, signed into law in 2023 by Maryland Governor Wes Moore, dramatically expanded the state’s enforcement capacity by:

- Granting the state’s Attorney General (AG) authority to investigate, prosecute, and remediate civil rights violations for the first time in state history, enabling pattern-or-practice lawsuits and class actions,

- Creating a Civil Rights Enforcement Fund from penalties and settlements to provide sustainable funding for enforcement activities,

- Authorizing the Attorney General to establish a Civil Rights Division and create the Office of Equity, Policy, and Engagement to proactively confront systemic inequality, and more.

Additionally, the legislation explicitly directed the state AG’s office to work with the existing Maryland Commission on Civil Rights, with the AG handling systemic cases while the Commission continues to review individual complaints.5 Maryland’s framework builds on existing state agencies rather than replacing them, incorporates a sustainable funding mechanism for enforcement, and provides both reactive and proactive enforcement tools to meet the state’s evolving challenges. Next steps for the state may include facilitating effective communication across the various agencies (while preserving the Commission’s independence), increasing mechanisms for collecting and analyzing relevant data, and expanding the office’s capacity to reflect the volume of effort necessary to enforce the rights of all residents.

Georgia

Georgia, governed by a Republican trifecta, is taking substantive steps to map the current landscape and develop recommendations to deliver on the promise of equal protection in the state constitution. In March 2025, the Republican-led state legislature established the bipartisan Senate Civil Rights Protections Study Committee,6 7 tasked with conducting a comprehensive review of the state’s existing nondiscrimination laws; identifying any gaps in protections; analyzing data and research on discrimination in employment, housing, public accommodations, and public services; and more. The State Senate directed the Committee to issue a resulting report examining other states’ civil rights laws as well as federal protections to identify best practices and outline potential legislation to address weaknesses in Georgia’s current infrastructure. The creation of this bipartisan committee reflects an important first step to strengthen Georgia’s civil rights protections, which are narrower than other states’.

Iterations of the idea

As the examples above illustrate, states have pursued different configurations for their civil rights infrastructures and are subject to their unique political and cultural dynamics. There is a path forward for every state, no matter their starting point, to build systems that work now and for the future. A fully realized state civil rights infrastructure would include the following elements:

- Comprehensive legal protections against discrimination.

- The appropriate state agency shall provide regular guidance and technical assistance to ensure that communities know their rights and to assist entities in complying with these protections through new and emerging challenges.

- State agency enforcement offices with:

- The authority to conduct robust investigations of private and state actors and secure compliance with applicable nondiscrimination laws,

- The authority to undertake both individual and systemic investigations based on complaints, data, and other relevant sources of information,

- The independence to conduct their work on a neutral basis without political direction, and,

- Sufficient staffing, informed by the population size of the state.

- Clear mechanisms to regularly collect and analyze relevant data to better understand and inform civil rights compliance.

- Resilient funding mechanisms that do not rely on federal sources,8 including potential alternative streams (see Maryland example, above).

Each component of this framework is an important element of a state’s broader infrastructure, but each can be pursued separately by policymakers aiming to shore up protections where they can. Some states may seek to expand protected bases under law or to improve enforcement.

Additions or clarifications of state nondiscrimination protections will require legislative action, whereas depending on the state, the governor and local entities may have authority to establish new and expanded enforcement mechanisms without new legislative approval. Once granted sufficient autonomy, designated agencies can implement enforcement efforts, guidance, technical assistance, data collection and analysis, and other activities.

Why act?

- We never should have counted so much on the federal government—to the exclusion of the states—to serve as a backstop for civil rights protection. Every level of government has an important role to play, responsive to the needs of our people.

- States have the power to fill this gap and protect their residents, but only if they build the infrastructure to do so. Every state already has civil rights laws on the books, but states generally lack the enforcement capacity, independence, and resources to make those protections meaningful. Without action, we risk returning to the patchwork of unequal protections that federal law was designed to remedy six decades ago.

- Building state civil rights infrastructure isn’t starting from scratch; it’s about strengthening what already exists. States can expand protected categories under law, establish independent enforcement offices with investigative authority, implement data collection to identify patterns of discrimination, and create resilient funding that doesn’t depend on an unreliable federal government.

- A viable starting point for a state is to conduct a thorough examination of its current civil rights protections to assess where there are gaps in the system, as Georgia is doing. It can then take steps to fill those gaps, including some of the actions laid out above.

- Strong state civil rights systems protect everyone. When students with disabilities receive the educational support they’re entitled to, when workers can report harassment without fear of retaliation, when families can access housing regardless of who they are, all of us have a greater opportunity to succeed.

- Whatever your state’s starting point, there are concrete steps leaders can take right now to deliver on our founding principles. Together we are equal to building the resilient, responsive systems our democracy demands.

End Notes

- Lhamon, Catherine E., and Seth M. Galanter. Commander-in-Thief: President Trump’s Withholding of Federal Funds from Universities Based on Alleged Discrimination Unlawfully Disregards the Procedures and Limits Adopted by Congress in the Civil Rights Statutes. Edley Center on Law & Democracy, Aug. 2025. University of California, Berkeley School of Law, https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Commander-in-Thief_Catherine-E-Lhamon.pdf

- Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Harmeet Dhillon described her objective as “turning the train around and driving in the opposite direction.” Monyak, Suzanne. “DOJ Leader Calls for Civil Rights ‘Paradigm Shift’ After Exodus.” Bloomberg Law, 5 May 2025, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/doj-leader-calls-for-civil-rights-paradigm-shift-after-exodus

- Mack, Andrea et al. “Iowa Governor Bill Removes Gender Identity from Civil Rights Protections.” NBC News, 28 Feb. 2025, https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-politics-and-policy/iowa-governor-bill-removes-gender-identity-civil-rights-kim-reynolds-rcna194301

- McCall, J. Holly. “Tennessee House Passes Measure to Dissolve State Human Rights Commission.” Tennessee Lookout, 17 Apr. 2025, https://tennesseelookout.com/2025/04/17/tennessee-house-passes-measure-to-dissolve-state-human-rights-commission/

- Maryland Senate Bill 540: Common Ownership Communities – Recreational Common Areas – Sensitive Information as Condition for Access. LegiScan, 2025 Regular Session, https://legiscan.com/MD/text/SB540/id/2815672

- Senate Resolution 444: Senate Civil Rights Protections Study Committee; create. Georgia General Assembly, 2025-2026 Regular Session, Georgia Senate, https://www.legis.ga.gov/api/legislation/document/20252026/236883

- Georgia’s state legislature periodically forms bipartisan committees to explore proposals of interest to the legislature.

- For instance, many states rely on the EEOC and HUD for a sizable share of their civil rights enforcement budget. These and other federal grants are an increasingly unreliable source of funding under the Trump Administration.