The Missing Liberal Story

A void has opened in American political consciousness. It’s time to abandon cautious messaging and develop an authentic narrative that voters can believe in.

- By Marshall Kosloff

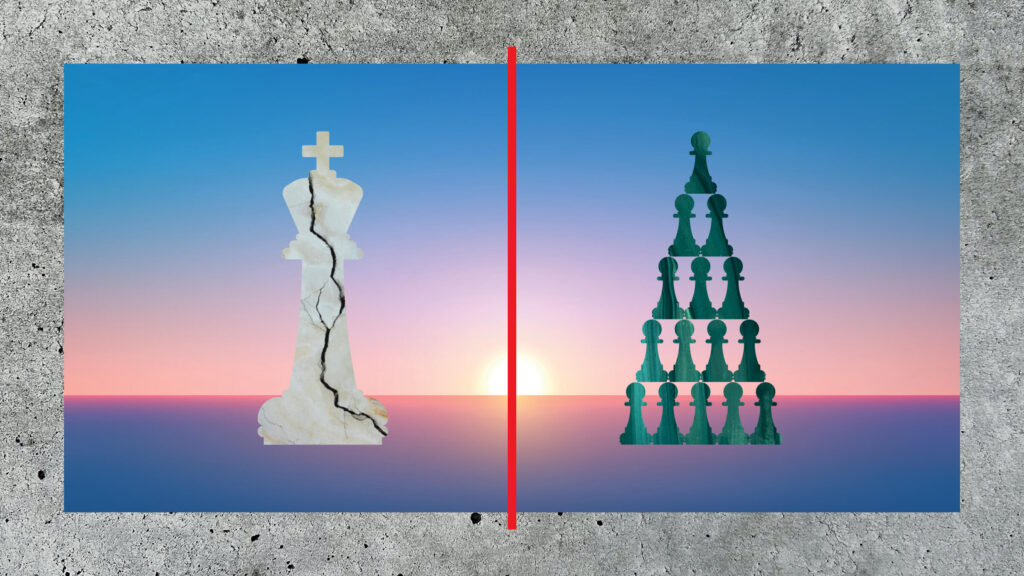

Presidential elections offer the winner a chance to implement a new vision and set the country on a different course. With Donald Trump’s victory in 2016, the MAGA movement created a more participatory ecosystem and a politics that leveraged influencers and alternative media to give voters a new way of making sense of their world. At the same time, the more technocratic center-left struggled to tell a cohesive story about liberalism, one grounded in common sense and a shared understanding of the country.

Both parties are shaping their respective narratives within a new political reality: a void that grew out of the mismatch between what people have been told they should believe about our institutions and governance and their actual lived experiences.

The key to successful post-2016 politics is an ability to tell an authentic, compelling story about America. Facing an anti–status quo electorate, winning candidates and movements are in a position to articulate what’s gone wrong, where we’ve been, and where we’re going. These stories can feature a wide cast of characters, broadly resonant themes, and clearly identifiable heroes and villains. And, like interactive theater, they welcome audience participation.

But until a candidate, movement, or party can tell that story in a way that not only wins backlash elections but successfully governs to the point of reelection and consensus, the political void that defines the second quarter of the 21st century will remain open. The opportunity to fill it (or prevent your opponent from doing so) is at the root of the exhausting political reality we now find ourselves in.

Nowhere in this essay will a reader find an exact articulation of what the liberal story should be. That is very much by design. As the host of The Realignment podcast, I have spent the past 10 years embedded in left and right populist spaces. Especially in the post-2016 early days, populists were less concerned with any one person’s specific answer and more interested in attracting participants to their project and asking the right questions. Over the years, unifying stories, ideas, and election outcomes built upon themselves to the point that something comprehensive was on offer in the 2020s.

My main argument is that interested parties should recognize that “story” is an underemphasized aspect of liberal politics, and shift attention and resources away from purely tactical topics and questions, which received outsized attention in 2025.

Now is the time for the left to gather narrative strands into a cohesive plan of action.

The narrativization of politics

Stories are at the root of the worldviews, ideologies, policies, and popular and memetic slogans that are the key drivers of politics today.

For example, when Wall Street speculation leads to a devastating financial crisis, as in 1929 or 2008, the belief that the government has a responsibility to intervene and regulate markets is a worldview. Policies are the implementation of that worldview (in this case, the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau or legislation regulating speculation).

The tools that politicians have traditionally wielded to reach the electorate—messaging based on polls and focus groups, and around individual candidates—still matter, but such data-centric, tactical approaches often miss the forest for the trees. Critically, they tend to underemphasize the visceral human factors that drive narratives and instead encourage a sterile, cautious politics that voters perceive as inauthentic and status-quo coded.

In this formulation, slogans matter, but it is difficult to inorganically create one with real narrative and memetic power. Donald Trump did not hire a consulting firm or panel of experts to come up with “Build the wall.” He arrived at it during the course of leading rallies bemoaning America’s immigration policy.

In First Principles for the 11th Hour, Adam Pritzker and Daniel Squadron negatively contrast a Washington-ruling conservative movement with a left-liberal project unable to “offer a compelling alternative.” This failure isn’t due to a lack of effort or opportunity. The past year saw countless autopsies, books, content creators, organizations, and polling try to fill the gap. Beyond the post-2024 reckoning, the past decade featured numerous attempts to explicitly counter the politics of MAGA.

For all of that effort, no slogan with the potency of MAGA has emerged. No single policy approaches the U.S.-Mexico border wall’s ability to galvanize a rally or go viral on social media. Ask the average voter to quickly identify and sum up any of the grab bag of policies proposed during the Biden administration, and many will likely come up empty.

These failures are rooted in a misunderstanding of what MAGA (and populism) is: a story-driven narrative that places a voter’s reality at its center. MAGA has a worldview, policies, slogans, and plenty of data-driven architecture. At its core, though, MAGA is a story about the past, present, and future of American politics. Any successful liberal alternative must begin by telling its own story.

Populist storytelling

During the past decade of political realignment, the populist right and left have been the best storytellers.

The MAGA populist story goes something like this: “Since the 1990s, bipartisan elites have driven the country into a ditch. They shipped jobs overseas, let in hordes of illegal immigrants who lowered wages and weakened our culture, let hundreds of thousands of Americans die opioid-fueled deaths of despair, and presided over disasters like the Iraq War. If you elect Donald Trump, he will overturn these elites and make America great again.”

The MAGA story is broad and flexible enough that new issues can be incorporated within it on the fly. At various points, the COVID-19 pandemic, “wokeness,” attacks on LGBTQ Americans, and fear of censorship were added to the narrative.

Meanwhile, left populists like Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Elizabeth Warren, and Zohran Mamdani are telling a story that goes like this: “Since the 1990s, the worship of neoliberal markets and the oligarchy that resulted have eviscerated the 99%. Supreme Court decisions like Citizens United enabled billionaires and special interests to buy even more power and influence over our democracy. Centrist Democrats like the Clintons and Obama made a devil’s bargain for power in alignment with these forces. Elect a Democratic Socialist and you’ll escape economic precarity.”

In our current media ecosystem, both the right and left version of the populist story can be articulated in a way that reaches a news-averse, apolitical swing voter. One can easily imagine discussing both with Joe Rogan.

Once the message is delivered, tangible policy proposals can emerge from both storylines: The right proposes to “build the wall,” reduce all forms of immigration, and defund higher education; the left pursues “Medicare-for-all” and vigorous antitrust enforcement.

Audience participation is likewise available to both sides—ranging from Trump’s rallies and boat parades to the Mamdani campaign’s scavenger hunt—with each side featuring a new and exciting cast of characters. No one had heard of JD Vance, Stephen Miller, Steve Bannon, AOC, Zohran Mamdani, or Lina Khan before 2016. And, as in a good play, even known quantities can make a surprise appearance—like RFK, Jr. and Tulsi Gabbard joining Trump’s cabinet, despite having run for the presidency as Democrats.

A key factor is that all the characters see themselves as participating in the same story, that everyone is reading from the same script. This is largely true on the right, but an open secret in Democratic circles is that many ambitious center-left to centrist politicians conceive of themselves as islands unto themselves, focused on individual races and brand building.

Post-2024, liberals and their institutions are lacking a cohesive story or a shared set of policies or a central cast of characters. There is no structural or ideological reason that liberalism fell so far behind. The problem is that liberals still own two of the main stories invalidated by the 2024 election and haven’t moved past them.

The first story was the bipartisan optimism of the post–Cold War 1990s. The worry that American workers might be left behind by globalization, as the country transitioned from an industrial to a digital economy, was largely dismissed. Instead, the left was promised Trade Adjustment Assistance to help send as many people to college as possible—comparable to how they had made high school education the norm in the 20th century. The prevailing belief was that America was on a path toward a diverse and progressive 2050, powered by the new economy and globalization.

The second story treated the populist revolts of 2016 as aberrations. The country was ultimately on the right path after the 2012 election, temporarily interrupted by Russian interference and a mismanaged Clinton campaign. We just had to get back on track with a return to normalcy and a Biden presidency that could “build back better.”

Any politicians still wielding either of these narratives will find themselves lost in 2026 and beyond.

Launching a liberal storytelling project

As noted above, there is no single correct answer to what the liberal story should look like. My aim is to encourage liberal proponents, organizations, and thinkers to orient themselves around building that story as a central aim. Anyone interested in pursuing the ideological project should follow these recommendations:

1. Fill the story-centric programming gap

Last year, I interviewed Representative Jake Auchincloss and Abundance co-author Derek Thompson at WelcomeFest 2025, an annual gathering of centrist Democrats. As I prepared for the interview, I was taken aback by the lack of a defined and unifying story across the remarks, panels, and interviews.

Alongside surveys of research-based autopsies of the 2024 election, there was plenty of focus on the tactical benefits of moderation and centrism, including the need to win swing-district elections. What remained unclear was what exactly these speakers and attendees believed (separate from poll results) about the country. This is in stark contrast to discussions in populist spaces, which engage in a very different ratio of storytelling to tactical analysis.

After chewing over the Abundance Agenda, I asked Auchincloss and Thompson about the lack of a story, specifically contrasting it with the populist approach. Auchincloss responded: “Let me start by saying I don’t know the answer to that question, and that’s okay.” Thompson provocatively argued: “ What I would say in response to that is, yeah, stories are for children. Americans need a plan. Americans need solutions.”

The extended version of their remarks offered more context, with Auchincloss emphasizing that a competitive and open 2028 primary would surface new ideas and Thompson arguing that many stories told by populists are “bullshit” and won’t actually address serious problems facing Americans. As a hypothetical candidate, Thompson would emphasize that his job wasn’t to be a “storyteller” but to actually deliver.

In my entire career as a podcaster, I have never received as much feedback on a single episode, with audience members agreeing and disagreeing strongly with both responses. An entire conference, journal issue, and podcast series could be organized around the challenge of storytelling, with serious arguments on both sides.

2. Acknowledge the authenticity gap

Danielle Lee Tomson, an academic and author of the forthcoming Under the Influence: What’s Real When America Feels Fake, defines the authenticity gap as “When our expectations of reality—shaped by the stories we collectively tell ourselves about how the world works—no longer align with our lived experiences.”

The stories of the populist right and left are premised on the existence of an authenticity gap. Imagine a 30-something millennial who went to college, worked hard, played by the rules, but still isn’t able to afford a house. This person will experience an authenticity gap between their understanding of the path to the American Dream and their lived reality. The same is true of a Gen Z recent grad who took the 2010s call to pursue STEM education and “learn to code” seriously, but who is struggling to find an entry-level job in the tech industry.

The populist right and left have clear stories that explicitly acknowledge these authenticity gaps, name villains, and propose solutions. Note that YIMBY policies and the Abundance Agenda are offered as a potential solution, but as polling demonstrates, zoning and other bottleneck-centered reforms, while correct on the policy merits, lack the narrative power of the populist alternatives.

3. Fill the liberal void

In a recent appearance on the columnist Ross Douthat’s Interesting Times podcast, Abundance co-author Ezra Klein said: “The loss of 2024 shattered the Democratic Party’s confidence in its own politics. I just don’t think that the new leadership, the new ideas, have yet emerged. One reason I think Abundance did as well as it did as a book and created so much energy—which was more than I thought it was going to create—is because it dropped into a void.”

Abundance and the organizations, conferences, thinkers, and leaders it inspired are a good start. Klein and Thompson seek to answer why post-1960s liberalism failed to build, and their attempt is crucial. Even if one disagrees with their conclusions.

However, filling the void requires answering other, often more profound, questions. What does it mean to be an American after the breakdown of our post-1965 consensus about immigration? What is the purpose of higher education in an era of artificial intelligence, the diploma divide, and a declining belief in college itself? How should America reorient its economy to compete with an increasingly innovative China? And, most crucially, how can Americans reclaim the idea that we live together in a shared culture, even as institutions and norms are breaking down and algorithms push us toward social atomization?

The post-2024 moment and our unfinished realignment leave us with too many questions for a single essay to contain. But it’s important to note that, even post-Trump, the MAGA conservatism that remains will provide a comprehensive worldview for answering them. The lack of a 2025 alternative from liberals or the Democratic Party is the void Klein refers to. There are no shortcuts. Focus groups, polls, and the usual, party-first suspects from Washington will not get the job done.

3. The future is fusion, not factionalism

While this essay contrasts the populist right and left’s effective storytelling with center-left liberalism, it’s a mistake to assume that a liberal story is fundamentally at odds with either populism or the center-left. Ultimately, the center-left and the left are in an ideological coalition predetermined by the structure of America’s electoral system. No single faction has a majority of the party, and none can seriously contest every political environment (centrists are weak in cities; socialists cannot win swing districts). They will then have to work together to govern nationally.

One of the biggest mistakes of the past year was the descent into factional infighting within the left-liberal coalition despite its shared opposition to MAGA populism. To pursue their ideological ends and govern, both the center-left and left can and must learn from one another.

Danielle Lee Tomson defines fusionism as “ideological factions that are clear about what they want to see in the world, with enough overlap and a common enemy.”

If one assembled every faction of the left-liberal spectrum in a room, they would agree on three things: the belief that government is a force for good; recognition of a broken status quo; and opposition to any MAGA successor to Trump. Agreement on the culture wars, antitrust policy, foreign affairs, climate change, taxation, and healthcare does not naturally follow from the initial consensus. An effective liberal story must be able to include a diverse set of ideological actors who may disagree on serious questions and even seriously dislike one another.

One of the biggest achievements of the 20th century conservative movement was its ability to unite a fractious set of actors, from Cold War hawks and anti–New Dealers to social conservatives and John Birchers. Conservative fusionism developed an overarching story and identified common enemies (New Deal liberalism and the Soviet Union) and selected leaders capable of navigating between the various factions. The left-liberal coalition should follow this model.

5. From story to an alternative politics

As emerged in my conversation with Derek Thompson, a story-first approach to post-2024 politics is certain to make many liberals uncomfortable. Stories feel unserious, especially in contrast to the technocratic, wonky, data-focused approaches in vogue in liberal spaces over the past decade.

Ironically, given Thompson’s dismissal of “stories,” his Ezra Klein co-authored, bestseller Abundance is a worthy first attempt. At its core, Abundance argues that the New Deal liberalism that built the postwar middle class ran out of steam in the 1970s. During that decade of post-Vietnam/Watergate malaise, liberals turned their attention to managing the costs of growth, especially as relates to the environment. Today’s liberal failures: the gap in housing construction between red and blue states, the inability to complete the California high-speed rail project, and the permitting and other construction obstacles faced by the Biden administration are rooted in a failure to embrace a “liberalism that builds,” as Klein calls it.

While this story is compelling on its own terms, it represents a necessary inward-facing critique of blue-state governance, not a model or vision for the country as a whole. Few if any voters outside California or Washington think tanks lose sleep over high-speed rail. Liberals should understand the conversation around Abundance as a key chapter of the post-2024 liberal story, but not the central narrative.

If our goal is building an alternative politics, one should consider a compelling story as merely the first step, not as a be-all and end-all. A story leads to conclusions. Conclusions lead to an ideology and a worldview. From there come specific policies, which can be turned into compelling slogans and attract a new cast of characters.

About The Author

Marshall Kosloff is the Niskanen Center’s director of special projects. He hosts The Realignment, a podcast covering post-2016 America. He executive-produces Endless Frontiers and Abundance conferences. Based in Austin, he is a senior fellow at the UT Austin Strauss Center and sits on the Recoding America Fund’s advisory council.