Preventing Authoritarianism

A conversation with Susan Rice

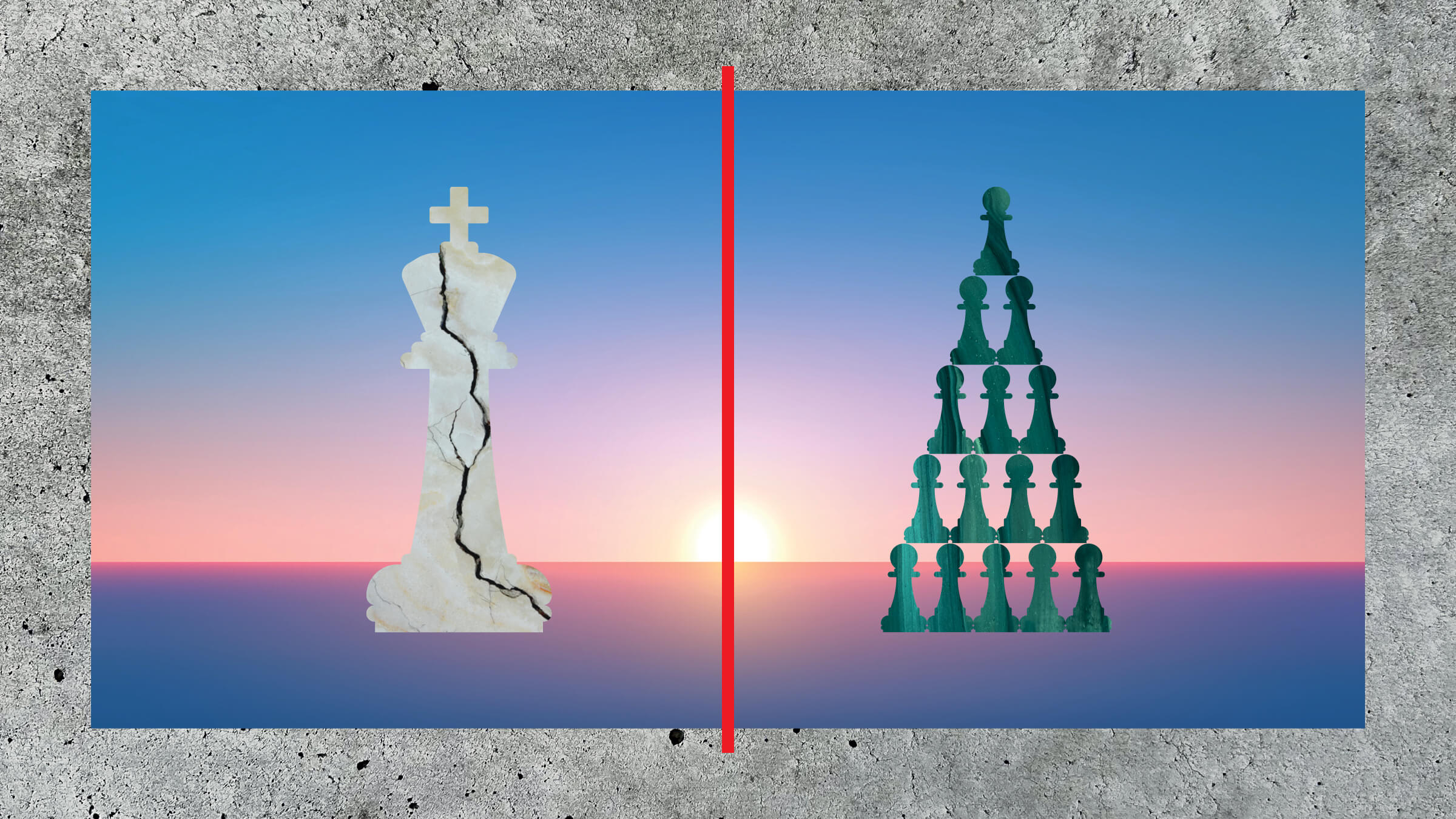

The United States constitutional order is in a fragile state—but it’s not too late to save our democracy.

- By Susan Rice & Lise Clavel

From her tenure as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations to her service as White House national security advisor and domestic policy advisor in the Obama and Biden administrations, Susan Rice has been a firsthand witness to the fragile nature of stable governance in countries grappling with the erosion of constitutional order. Over a 30-plus-year career in foreign and domestic policy that has spanned three presidential administrations, she has developed a rare perspective into the mechanics of power and the patterns of its abuse. Having navigated the complexities of international regimes across the spectrum of democracy and authoritarianism, Ambassador Rice understands that American democracy is not a passive inheritance but an active pursuit that calls upon every state and local leader and citizen to engage in the fight to preserve our republic.

Critically, at every turn she makes clear that we have not descended into authoritarianism with no turning back—yet. Rather we are in a critical moment that will determine the path of our country: whether the American Promise—representative democracy, personal freedom, fair markets, and effective government—will persist or these founding principles of our country will be abandoned. States, with their independent powers in our federal system, can and must be at the center of the effort to uphold that promise. Throughout the rest of the journal, readers will find a host of provocative ideas for how states can respond to the moment Ambassador Rice describes.

In a series of conversations in December and January with The States Forum Executive Director Lise Clavel, Ambassador Rice spoke about the embattled state of American democracy and how to safeguard its future.

Lise Clavel: You know what authoritarianism looks like in other parts of the world. Do you believe we are in an authoritarian moment in the United States? And what kinds of comparisons can you make to what you’ve seen in other countries in the past decade or more?

Susan Rice: Yes, I think we are well on the path to authoritarianism. A good way of thinking about it is the way that Steven Levitsky, Lucan Way and Daniel Ziblatt, two of whom are the authors of How Democracies Die, wrote about it recently in Foreign Affairs. They talk about how we have already descended into what they call “competitive authoritarianism,” where an elected government slides into authoritarian actions and tendencies but there’s still some space for political competition, even if the playing field may not be level, and still some opportunity through action and organization to slow or arrest that slide and eventually reverse it. I think their assessment is absolutely correct. We’re in a bad place and it’s getting worse, but it’s not yet irretrievable.

Where else have we seen situations like this? We’ve seen it in India under Indira Gandhi. We’ve seen it in Poland. We’ve seen it, obviously, in Hungary, in Turkey, and to greater or lesser extents in a number of other places—Malaysia, Serbia, even Ukraine. In many of those instances, even long-lasting slides into authoritarianism have been reversed. In some of them it hasn’t.

LC: In your assessment, is there a red line that if we cross it, we’re out of competitive authoritarianism? When are we just there?

SR: I don’t know that there’s a single red line, but I will point to indicators that for me are tipping points. Turning the American military against civilians. Trump threatened to do that during his campaign and as president. He’s talked about using the military against the so-called enemy within. Going from invoking the Insurrection Act to invoking martial law and suspending habeas corpus, all things that Stephen Miller has threatened to do. If we get to the suspension of habeas corpus, we are no longer living in a democracy. And martial law or a state of emergency used to justify suspending elections or any other excuse to not have an electoral process on a level playing field. The playing field is already not level, but you can go from a not-level playing field to no playing field at all. That would be another shining red line.

LC: Does DHS’s killing of two U.S. citizens, Renee Good and Alex Pretti, in Minneapolis cross the line?

SR: I don’t think there’s a single red line. We’re definitely on a very frightening path to authoritarianism. But whether we’re at the 30-mile marker or the 50-mile marker or the 100-mile marker is debatable, and not that relevant.

Here’s what’s relevant: The rule of law has been abrogated, consistently; that only happens in the context of authoritarianism.

We see it … with American citizens having their windshields smashed in and being dragged out of their cars and slammed to the streets and beaten and disappeared into detention without access to lawyers and families. We see the homes of American citizens being raided by masked men from Chicago to Oklahoma City to Minneapolis.

We see it most of all in the brazen, wholly unjustified, unnecessary killings, indeed executions, of unarmed American citizens Renee Good and Alex Pretti by federal law enforcement. Then Trump and his minions tell the public bald-faced lies about what happened and smear the victims, both law abiding and upstanding U.S. citizens, as “domestic terrorists.” Moreover, Trump’s DHS and DOJ block any independent investigation of the shooters and instead demonize their surviving loved ones. It’s Orwellian and despotic. But the majority of Americans see through their lies, still believe in the inviolability of the Constitution, and are outraged. So, that’s where we are.

And if it can happen to an American citizen, regardless of their background, country of origin, natural born, however many generations their family’s been here, whatever their race, religion, you name it, it can happen to anybody. And that’s what we are starting to see. We are seeing kids, veterans, police officers, people of all regular walks of life, all of whom are American citizens, being confronted, detained, and sometimes secreted away and denied access to counsel and family.

Those are Gestapo-like tactics. I don’t know what else to call it. And that, to me, is indicative of lawlessness. Moreover, when an ICE officer shoots an unarmed civilian in her car who had just dropped her kid off at school, when clearly, at least according to the video, she did not pose a direct threat, the agent goes out of his way to shoot her in the car rather than tell her to pull over or disable her tires, and the response of the authorities is, “She got what she deserved because she was disrespectful.”

When you get Trump and Vance lying and justifying the murder [of Renee Good], and then declaring that not only the officer involved but all ICE officers have “complete immunity”—which is a legal fiction—and that literally means complete impunity, because according to the president, they can do whatever the hell they want. That is crossing the Rubicon into a completely different space. An unambiguously authoritarian space. And it means that none of us have our basic civil liberties, or none of us can count on our basic civil liberties being protected.

LC: Do you think state and local prosecutors should charge federal agents, as some Minnesotans are demanding should happen with the agents who shot Good and Pretti?

SR: I’m not a lawyer, but they ought to have the ability and the right to investigate; those committing potential crimes are definitely worthy of investigation and potentially worthy of prosecution. They need to understand that if they’re not going to face federal charges, they may face state or local charges. I’m not the expert on where the jurisdictions lie, but we can’t be in a situation where so-called complete immunity literally means that federal officers can do anything, anywhere. If they attempt to implement that, I certainly think state attorneys general need to challenge that—rapidly and in unison. It’s a crazy concept.

LC: Just this week [January 26], lawmakers have raised concerns about funding for DHS, ICE, and Border Patrol. The Senate is set to vote on the upcoming appropriations bill, with many in Congress, including Senator Schumer, insisting they will not vote for the current bill without major reforms. What’s your view about what Congress should do?

SR: I think it’s absolutely essential that Democrats insist on getting ICE and CBP out of Minnesota and on serious reforms to the way ICE and CBP and other DHS entities are conducting operations in American communities more broadly. It would be malpractice for them not to use the current fiscal year appropriations bill as a vehicle to try to effect those changes. The Republicans will be to blame for a wider shutdown if they don’t go along with separating out the Homeland Security appropriation from the other funding bills, which the Democrats have no objection to, and Republicans would be remiss not to negotiate with Democrats to put serious constraints on how DHS is operating: It’s hugely unpopular with the American people, it’s lawless, it’s unconstitutional. If Republicans want to put themselves on the side of being against the Constitution, Democrats should fight them every step of the way.

LC: There have been reports of ICE using digital surveillance to track not only immigrants, but U.S. citizens who lawfully observe or protest ICE actions. Tom Homan recently said that DHS would build a database of people who are interfering and “make them famous,” essentially threatening to dox them. How do you compare such threats to what authoritarian regimes like China have done?

SR: Surveilling American citizens who’ve not committed any crimes without a warrant is illegal, and to the extent that may be beginning to happen—I’m not going to say we’re comparable to China, but we have a right to privacy, we have protections of our property and our person that are constitutionally guaranteed. If those protections are denied or abridged, that’s a very serious thing. It’s illegal, and it needs to be treated as such. We can’t normalize a surveillance state for whatever purpose. The whole notion that anybody who dissents or objects is a terrorist is another brick in the wall of lawlessness and authoritarianism.

LC: Do you think the administration’s recent actions in Venezuela and the current threats to Greenland and Europe fit into the broader slide to authoritarianism we’re discussing?

SR: Regardless of how criminal, evil, dangerous Maduro was, there is no question that the brilliantly executed military operation to snatch him and bring him back to the United States violated international law. I don’t know a single expert on national security or international law who would disagree with that. Now, this administration has said very plainly, they don’t give a flying you-know-what about international law. And they also are increasingly demonstrating they don’t give a flying blank about domestic law either. These are two sides of the same coin. You can disparage international law, but by ratifying treaties that bind us—to the UN Charter, or to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, or whatever—we have incorporated that international law into domestic law. And when we dismiss it when it’s inconvenient for our purposes, we become lawless. We’re more than imperialists; we’re rogue actors, just like Russia. And the threats to Greenland are to me in a category all by themselves. Any military action, any extreme coercion that would result in, effectively, an effort to take over Greenland, would be the death knell of NATO, which has been our most important alliance, our superpower special sauce when it comes to competing against adversaries like Russia and China. They envy our alliance system in the Atlantic and in Asia. And that’s why the best gift we could possibly give to Vladimir Putin—and by extension to Xi Jinping, but especially to Vladimir Putin—would be to rupture NATO. That’s the course Trump seems to have been on. Maybe he’s pulling back. Maybe he’ll change course again. You never know what side of the bed he’s going to wake up on. But he has obliterated trust. Even if he refrains from trying to take Greenland by force, the fact that he would repeatedly threaten that, and then repeatedly threaten our NATO allies with tariffs for standing up in support of their Article 5 obligations, which we should be supporting, to defend a NATO partner against attack, it just shows that he’s governing by whim and that they cannot trust the United States of America under Donald Trump. That’s incredibly detrimental to our national security.

LC: Can our relationship with Europe really be undone as fast as it looks like it could be undone?

SR: We’re watching it happen, perhaps in fits and starts, but the greatest recent example is what Canada’s been doing. Canada has been screwed by the United States economically. Canada has been threatened to be annexed by this president. They’ve recognized that they can’t continue to put all of their economic and security eggs in the American basket. It’s too damn risky. So they’re diversifying their economic and security relationships. A lot of Americans have their knickers in a knot about Mark Carney going to China and declaring a new strategic relationship. Nobody would like to see that, in an ideal world. But from the Canadian point of view, at least China’s not threatening to invade and turn them into a province. We’re putting our friends in an impossible situation, where they either have to become completely subservient to us or they have to make choices and diversify their economic and security relationships in ways we don’t want to see them do. That’s the folly of Trump’s approach. Carney gave a speech at Davos in which he laid out the path that middle powers who don’t want to be subjugated ought to pursue. It’s pretty much a sayonara to the United States. It’s “We can’t count on you. We can’t count on the rules-based international order. You’re a rogue state and you’re on our border.” That’s a hell of a message, but it’s reality. And it’s a reality that Donald Trump has created in 12 months. It is really extraordinary.

LC: The realignment of security interests makes you wonder whether other states may try to capitalize on Trump’s approach. Relatedly, I want to ask you about Viktor Orban. You were U.S. ambassador to the UN when he returned to power in 2010, and national security advisor when he began to take Hungary toward authoritarianism. What are the strategies he used that were most effective in undermining democracy?

SR: I’m not an expert on Hungary. But what Orban did was to co-opt the media, undermine universities, and go after civil society dissenters and individuals that could resist his authoritarian takeover. Trump is following his playbook to a T. It’s the classic playbook of an orchestrated repression of opposition.

LC: As of months or certainly a year ago, many people would have said this is something that can’t happen here, in the U.S. Do you have a theory about how we landed in this moment, in which norms and institutional safeguards are not working?

SR: Trump represents a degree of lawlessness and power and aggrandizement that exceeds anything we’ve seen in my lifetime. It far exceeds Nixon. And he signaled his comfort with pursuing lawlessness before he ran for office the first time. When you try to discredit the sitting president of the United States [Obama] with a bald-faced lie about birtherism, when you make that the launching point for your campaign, when you openly brag that you could walk down Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and get away with it: That kind of mentality is now what we’re seeing operationalized as policy by the president. And so I date the slide at least as far back as 2015.

But we have to understand that what Trump is doing is uniquely Trump. And what it has exposed is that our system of guardrails and laws and checks and balances is very fragile. We learned in Trump’s first term how much of what we expect to be normal is based on norms rather than laws. For example, the idea that, post-Watergate, the White House doesn’t get involved in directing the Department of Justice in how to pursue prosecutions. That’s totally fallen by the wayside, and we have a completely hijacked and politicized Justice Department with the president publicly instructing them to prosecute his perceived enemies. There’s no law against that; it was just a norm and a custom.

We have a system that depends on a separation of powers. But if Congress and the judiciary abdicate their roles, as Congress completely has, there’s no check, and the president can usurp fundamental powers like the power of the purse. When you have a court system that, at least at the senior levels, like the Supreme Court, seems to be unwilling to check most presidential assertions of power, granting the president of the United States almost complete immunity for anything he does while in office, that’s a recipe for lawlessness.

The guardrails were weak in the first instance, or normative rather than legal in many instances, and have failed substantially because of an unwillingness of institutions to play their constitutional role. And other power centers—whether private-sector leaders, corporations, law firms, or universities: Too many have cowered in fear and capitulated. Unlike in the first term, they have rolled over and played dead rather than stand up for their independence. So we’re seeing those kinds of checks eroding. And when you have an administration that is happy to label as a “domestic terrorist” anybody who disagrees with them, with this crazy-ass executive order against antifa, it’s very hard to see where the limits are.

LC: We’ve seen other countries descend toward authoritarianism and come back from it. Can you speak to how they’ve done that? What are the unique elements of American institutions that should make us optimistic?

SR: This is an interesting place to direct people back to that article in Foreign Affairs, “The Price of American Authoritarianism,” by Levitsky et al. They do a good job of chronicling places where setbacks have been reversed. India after Indira Gandhi. Malaysia after many years of authoritarian rule, where opposition forces managed to win an election in 2018. Poland, more recently, Serbia, and elsewhere. It’s often through electoral success that authoritarian regimes are thrown out, even when the playing field is grossly unlevel, because popular opposition is so great, with alliances forged across traditional political lines. There’s a coming together of forces that, for various reasons, find the authoritarian slide to be antithetical to their interests or values. What succeeds is a combination of contesting aggressively and in a unified way at the ballot box, fighting in the courts, and utilizing the street. Peaceful, sustained, nonviolent protest on a mass scale with a high degree of frequency and regularity.

What they conclude, which I think is right, is that at the moment the United States is well ahead of many other places in terms of our capacity to resist and halt or reverse an authoritarian slide. Obviously, the midterms are very important for that. But the advantage we have over other instances of much weaker democracies is, first of all, we have a unified opposition in the form of the Democratic Party. At the state level, through federalism, you know, in our governors and mayors, we have a significant capacity to put forth alternatives and to push back. As frustrating as the capitulation of many in the private sector and civil society has been, we still have a robust private sector. We still have a robust civil society. We still have robust philanthropy, which is why they’re trying to target civil society through this antifa executive order. The reality is, if people understand both the urgency and the severity of the challenge we face and recognize that we’re not defeated, all is not lost. We can’t give up. We have to organize and push back peacefully. And we have to do it quickly. The longer this goes on, the harder it is to arrest the slide to authoritarianism.

LC: We’re already seeing the Trump administration make these venal redistricting plays. What keeps you up at night about the midterms?

SR: The midterms are crucial. We’ve got to organize, we’ve got to vote, we’ve got to put up good candidates—we’ve got to do all the things that win elections. We also have to recognize that they’re already working hard to make this as unlevel a playing field as possible. Redistricting is the most obvious example. But they’re also suing states to get detailed information on voter rolls. Why? They are dismantling within the Department of Homeland Security the infrastructure that protects election integrity. And they put a crazy loyalist, an election denier, in charge of it. They’re also praying to God that the Supreme Court in the voting rights case makes it very easy for Southern states to kill minority-majority districts. So it’s already not going to be a level playing field. It doesn’t mean we can’t win, but it does mean that we’re going to have to work a lot harder. We’re going to have to have good candidates, and we’re going to have to recognize that they’re trying to stack the deck against us.

What worries me more, though, is if they become desperate, if they become convinced that despite all of that manipulation they still can’t win, that they will resort to more extreme measures. I’ve described the measures that I worry about, from using the military to intimidate people on the streets, at polls, to something even more serious, which is turning the military against the civilian population or invoking emergency authorities to postpone or suspend elections. I don’t necessarily believe that’s likely, but I think it’s very possible and we can’t rule it out. So we have to be vigilant as we prepare for elections the normal way, and think about what kinds of extreme measures they might conceivably take that they themselves have put on the table

LC: Another unprecedented approach of the Trump administration has been their deployment of federal power for explicitly partisan political ends. That includes using federal authority as a means to attack states and cities whose leadership it doesn’t like. Can you talk about how the federal government usually approaches its relationship with states, whether the leadership is from the same or the opposing party? And how, in your role as domestic policy advisor, you thought about domestic policy and the role of state leadership, even when there were underlying political disagreements?

SR: Our constitution has created a federal structure where there are clear rights and obligations that are reserved for the states and clear authorities that are federal. It’s pretty stark in how it’s laid out. Most administrations that I’m aware of—and certainly the ones I’ve participated in, the Biden, Obama, and Clinton administrations—respected the role of states, we tried to work collaboratively with states and treated their people as our constituents, whether they were red states or blue states, whether they voted for us or not. The most obvious contrast with Trump is with natural disasters. When people were suffering, we didn’t punish them because they lived in a red state. We granted swift emergency declarations and gave them the full federal support they needed—even [governor of Texas] Greg Abbott when he was doing anything he possibly could to screw the [Biden] administration. Meanwhile, Trump doesn’t want to give a dime to Maryland or New York or other blue states. To break it down even further, the part of Maryland that needed the most emergency support [after catastrophic flooding in May 2025] was Western Maryland, the Frederick area, out on the panhandle. That is Trump territory. He doesn’t care.

Every prior Republican and every Democratic administration has treated the states with respect, treated governors with respect, consulted them, collaborated with them, and tried to find common ground. If you look at how [the Biden administration], for example, crafted the Inflation Reduction Act, we went out of our way to try to ensure that the benefits were felt and received, arguably disproportionately, in red states, perhaps partly out of the hope that it would insulate the IRA from the kind of political backlash that Trump has orchestrated. But we didn’t treat states differently or unfairly because they may have had a Republican governor or tended to vote more Republican than Democratic. We respected the federal structure and responsibilities that were arrogated to the states versus those that are clearly federal—I’m not trying to say perfectly in every instance, but generally, that was the intent and the effect.

LC: The Trump administration has also endeavored to use federal power to pit states against one another, the most notable example being deploying the National Guard from one state to another over the objections of the receiving state’s leadership.This seems both dangerous and a real fundamental breakdown in our traditional understanding of federalism. What worries you most about such a move?

SR: The first thing I’d say is, it’s dangerous because what goes around comes around. A Republican governor [of Oklahoma, Kevin Stitt] basically said that if Joe Biden had sent troops from another state into mine, we would have gone batshit crazy. You are setting a precedent that can be used against you. Second, any student of history understands that we have a very bad track record in this country when states are pitted against each other. We had the deadliest war in our existence over this with the Civil War. It’s not something we should be playing with, particularly in this political environment. I would also argue that, however polarized and partisan we are, the president of the United States, until Trump, has viewed it as his job to serve all of the people in the country, not just the people who voted for him. Trump has changed that, to the great detriment of, not just of half the country, but of the country itself. That’s going to be a hard bell to unring. I think it’s playing with fire.

LC: What are the most important things people should be doing right now?

SR: Recognize the gravity of the situation. Go to school about what has happened and succeeded in other countries and in our own. Our own Civil Rights Movement is an important chapter of history that we need to understand and implement lessons from. One lesson is that a critical element is sustained, mass, peaceful, nonviolent protest. Not once every three months, like No Kings. I’m not criticizing No Kings, it’s great. It’s just not sufficient and not frequent enough, not sustained enough, and not yet at a scale that’s necessary. People have to recognize that no leader is going to descend from heaven to save us. We’ve got to save ourselves. And we can, but we’ve got to be brave. Boycotting entities and organizations and companies that have capitulated and bent the knee, or implemented policies that are antithetical to a democratic, inclusive society is another thing. And, obviously, vote and organize to make this midterm election as sweeping a victory as possible. Those who are contesting authoritarian overreach in court deserve our support and encouragement. But it’s elections, it’s the courts, it’s the street—peaceful, nonviolent protest, citizen action, including things like boycotting.

LC: Many of us who know you well believe you are a leader who could be part of getting us out of this.

SR: Well, thank you; I’m committed to doing all I can.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Editor’s Note: Lise Clavel worked under Ambassador Rice when Rice served as President Biden’s domestic policy advisor.

About The Authors

Ambassador Susan Rice is the only person ever to have served in the White House as both U.S. national security advisor and U.S. domestic policy advisor. She served as President Biden’s domestic policy advisor from 2021–2023, as President Obama’s national security advisor from 2013–2017, as the U.S. permanent representative to the United Nations and a member of President Obama’s cabinet from 2009–2013, and as assistant secretary of state for African affairs under President Clinton from 1997–2001.

Lise Clavel is the executive director of The States Forum. She previously served in the Biden and Obama administrations and held positions as a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and as a fellow at the Karsh Institute of Democracy at the University of Virginia.