Renewal to the Core

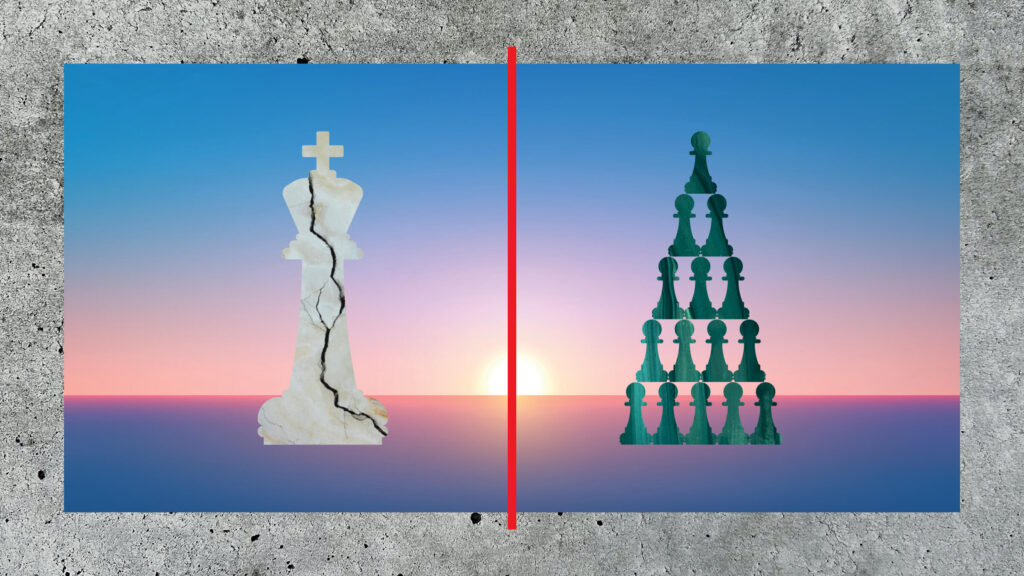

Renewal won’t come from entrenched elites. It will come from the outside in. And states are the best place to start.

- By Adam Pritzker & Daniel Squadron

For years, poor and middle-class Americans lived by the aphorism that they saw themselves as not rich—yet. They believed in their own shot at upward mobility. That optimism was a sign of belief in the system, which translates to support for those who would strengthen it, rather than replace it with chaos.

But over the past 20 years, defending the status quo has increasingly become a failing political strategy. The country’s mood has pickled from change we can believe in to burn the whole thing down. This is why a dangerous thread of authoritarianism has gained such purchase in political dialogue. It’s true from far-left to far-right. In fact, the greatest growth in skepticism about democracy cuts across ideology and geography—it’s concentrated among young people.

Recent national surveys find that while most young Americans still support democracy in principle, nearly one-third of those aged 18–29 are disengaged from democratic participation and more open to authoritarian alternatives, a level of skepticism far higher than among older generations.

This seems a completely unsurprising outgrowth of another often noted feature of contemporary American institutions. Across universities, law firms, and the government, institutions today increasingly function as “gerontocracies” where a narrow cohort of elite boomers and older Gen X monopolize decision making despite millennials and Gen Z possessing deeper fluency and more influence with the cultural codes and technologies reshaping society.

The resulting concentration and corruption of power creates structural misgovernance of the future that fuels hopelessness and cynicism, and, at its worst, opens the door to authoritarianism.

This gerontocracy fuels a schism in American culture, civic life and, downstream of them, politics. While its source is generational, its impact is not limited to certain age groups. The cultural impact influences older members of society too, the majority of whom didn’t make it to the elite sphere of influence and now also feel locked out of influence and power.

In Congress, the median age now exceeds 58 in the House and 64 in the Senate, near historic highs; the average American college president is almost a full decade older than 40 years ago; and the average Fortune 500 CEO is nearly 58, with many remaining in office well into their 70s and 80s.

While the ever-longer periods that ever-older leaders cling to power is the sharpest definition of the gerontocracy, we believe that the concept is closely related to a general ethos among elites across age groups akin to high priests in times of yore—a cohort whose own sense of their extraordinary accomplishments, great insights, and deep understanding of the world has earned prerogatives that justify their control over “mere” citizens.

A gerontocracy is not just defined by who sits in the top positions of elite institutions. Younger generations are excluded from power, but also from economic success. The average age of a first-time homebuyer has climbed to 40, and nearly 70% of millennials report that they cannot buy a home or retire, reflecting rising housing costs, stagnant wages, and diminished access to traditional wealth-building pathways. And they exist in an information ecosystem that amplifies takes (half-baked or not) that are designed to stoke that anxiety. Young people not believing they’re able to achieve even their parents’ standard of living is another version of gerontocracy, one that causes a loss of faith in the American Promise.

There’s no great insight in pointing out that corrupt, concentrated power undermines both the practice of and belief in democracy. Large cross-national studies consistently find that high concentrations of economic and political power correlate strongly with democratic backsliding, declining institutional trust, and reduced public confidence in representative government.

Political professionals often forget that for people’s lived experience—driven by bills and culture, relationships, and jobs—concentrated power isn’t coded politically. But the outcomes for politics (and therefore people’s lived experience) are profound. Systems with a small entrenched elite or unaddressed social fissures can appear stable while actually being fragile, leading to cascading failures that happen slowly, then all at once. Everyone inside the Soviet Union knew the system was failing, but the social and political costs of saying so kept people silent—until suddenly they didn’t.

As the contributors to this edition of The States Forum Journal describe from multiple perspectives, any sense of stability in this moment is illusory.

We’ve struggled with this as well. Like many others, we’ve benefitted from the wisdom and generosity of older mentors. Similarly, we know that numerous insiders are brilliant and effective. But the point is not about any individual—and the stakes are too high to tread carefully for fear of being misunderstood.

Inertia might feel like safety, but given the state of American politics and our economy, it is the most perilous possible choice. The problem is not that people no longer trust the integrity of institutional power structures and the people who lead them; the problem is that these structures have failed to maintain people’s trust. That is partially a judgment about those in charge and, just as much, a judgment about the possibility of participating in and benefitting from those structures for everyone else.

The fact that so many Americans, especially young adults, are skeptical of democracy, dread the future, and feel locked out of power is not a marginal concern that requires institutions and leaders to smooth the edges. It is a crisis emanating from the core of power and from the assumptions of people within it.

Although we are in a perilous moment, we feel genuine hope. At The States Forum, we believe that the journey we’ve been on together to build and wield the power to achieve the American Promise in states has brought us to the best possible place for this moment. In an ossified system collapsing from within, states are a soft spot closer to the edge—a constitutional cure to reinvigorate a failing body politic.

In states, there are lower barriers to entry for new leaders. Younger, less-wealthy candidates can run and win. You don’t need 30 years of institutional credentialing to represent 50,000 people.

And states are where meaningful progress can be made to strengthen the pillars of our country to which we’ve committed ourselves—representative democracy, personal freedom, fair markets, and effective government.

The risk created by the lack of faith in institutions and their leaders has another dimension, as risk always does: opportunity. For 250 years, our system has proven extraordinarily adaptable, reinvigorating itself at times of greatest stress. In each period, it has pushed our country ever closer to our founding declaration. The Civil War ended slavery and gave us a stronger constitution. So did the Progressive Era, the New Deal, and the Civil Rights Movement. None sprouted from periods of stability and faith in the leaders of the old guard.

They were hard-fought and necessary victories that came from both turmoil and stagnation, and a crisis of faith in the American Promise itself. We are living in such a period again.

But we do not despair. The task is clear: Win against the forces of authoritarianism and then, every bit as important, make the American Promise real in people’s lives.

About The Author

Adam Pritzker is an investor and entrepreneur interested in business, civics, and politics who co-founded General Assembly, Khaite, The States Project, and The States Forum. He serves on the board of directors for the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) and as lead director at Artium AI. Adam is a trustee of Columbia University and a board member of the Columbia University Investment Management Company.

Daniel Squadron was elected the youngest member of the New York State Senate in 2008, where he served for nearly a decade. He co-founded The States Project and The States Forum, initiatives of Future Now, where he is president. A graduate of Yale College, Daniel co-wrote Chuck Schumer’s book Positively American. His book, The Fourth Branch: How State Government Can Save Our Union, is being released in June.