How State Legislators Can Rebuild Trust in American Democracy

- By Alexander Hertel-Fernandez

Across the globe, citizens of many countries are expressing dissatisfaction with their governments. Since the 1960s, Americans’ trust in government has been in decline; as of 2024, a fraction of Americans say they trust Washington to do what is right, whether that’s “just about always” (2%) or “most of the time” (21%). For political leaders and politicians who seek to use government to address social and economic problems and build a multiracial, egalitarian democracy, this decline in trust poses a serious problem. Not only does it help fuel right-wing populist backlash to democracy, it also makes it harder to affirmatively use government to create new policies and programs to address social and economic ills.

The task of governing at this moment thus requires lawmakers and government officials to design policies that foster greater faith and confidence in government and democracy. One important way for policymakers to achieve this is by engaging members of the public in the design and implementation of public programs, especially in ways that build on trusted intermediaries—such as unions, faith groups, and other community-based organizations. Indeed, studying the experiences of dozens of rich democracies, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has recommended that countries pursue such engagement as part of a comprehensive strategy to rebuild trust in government. In the United States, state legislators have an important opportunity to design and launch public-engagement initiatives that draw in civic organizations with the programs their states already implement. In doing so, states can utilize policy as a means to reshape and reinvigorate our political culture while simultaneously reconnecting government to the citizenry.

For example, the most important safety net programs in the United States are operated as partnerships between the federal government and the states, with state governments holding a significant role in designing how those programs operate—including programs providing health insurance, housing support, food assistance, and cash welfare. To date, however, rarely have these programs meaningfully incorporated the perspectives of the people they serve on an ongoing basis. But promising evidence suggests that when policymakers do build in opportunities to engage Americans in meaningful ways, especially when building on civic institutions and associations they trust, it can redound to the benefit of both program implementation and the participants themselves. In addition, as my research has shown, building civic organizations into the implementation of public policies makes it more likely that beneficiaries will recognize the positive role of government in their lives and credit the politicians responsible for policy enactments in ways that simply receiving government support does not.

Take one example that I have studied closely: The unemployment insurance (UI) system offers a critical lifeline to unemployed workers and their families, as well as economic stimulus during recessions. At the same time, many eligible workers struggle to access benefits to which they are entitled, confronting dense forms and letters, hard-to-navigate and clunky websites, and confusing eligibility requirements.

The result is that in recent years, leading into the COVID-19 pandemic, only around 20% of eligible unemployed workers reported actually receiving benefits. Many workers fail to apply at all. Of those who applied for benefits, many report a high level of stress with the process. In a recent survey of UI applicants between 2019 and 2024, I found that nearly 70% either strongly agreed or somewhat agreed that the experience was stressful. More concerning, only half of respondents agreed that they had been treated with respect, a feeling that furthers the disconnect between government and the people it seeks to serve.

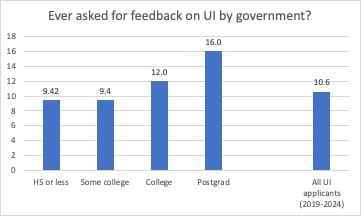

Part of the problem is that UI systems have not created meaningful mechanisms for workers to share their experiences with government staff, or for staff to respond to their concerns. In the same survey, just 11% of UI applicants reported that they had ever been asked about their feedback on the UI system from government staff—and these tended to be disproportionately workers with higher levels of formal education who were more likely to be consulted.

This skewed engagement matters, because unemployed workers with less formal education face some of the steepest barriers to accessing UI benefits and are least likely to apply for them as a result.

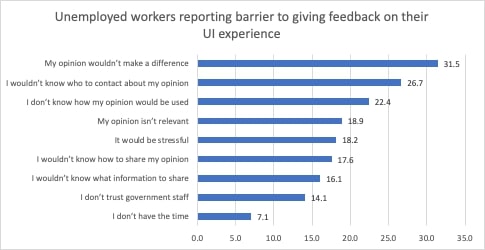

Even if agencies were to provide more opportunities for feedback, however, a significant obstacle is a lack of trust and sense of efficacy around engagement with government. When I asked UI applicants about sharing their feedback about their UI experience with the government, the most common barrier respondents cited was that their opinion wouldn’t make a difference—nearly a third of UI applicants said that this would make them unlikely to respond. A large proportion of UI applicants also felt their opinions weren’t relevant and didn’t know how their feedback would be used. The issue is not just building structures for more engagement—it is about overcoming the lack of trust many communities feel in government and showing clearly to them how their responses will be used.

As an alternative, imagine if state UI agencies regularly engaged groups of unemployed workers to better understand the barriers they were facing to accessing benefits, and then rapidly pressure-tested solutions to overcome those barriers. Such engagement could serve a dual purpose. It would provide an early-warning system for issues that might be lurking on the horizon with a state UI system—such as a broken website or a growing population of unemployed workers who face specific language barriers. And, as workers raised issues to government agencies and those agencies visibly addressed them in short order, the initiatives could help rebuild trust among workers by proving that government has the capacity to both listen to their concerns and, based on what it has heard, address the problems in their lives.

Although no states have a permanent program like this at scale, several have experimented with promising pilots in recent years. While serving in the Biden-Harris U.S. Department of Labor, I was excited to support a small group of states in implementing UI outreach programs that partner with community-based organizations, such as unions, legal-aid clinics, and other civic groups serving low-income and immigrant communities, to help connect workers with UI benefits and related job training and search services. Importantly, the program asked states to prioritize building partnerships with community groups that had a genuine base of members in the communities they sought to serve. These groups then served as navigators who were able to help people negotiate the often confusing bureaucratic requirements that stood in the way of their accessing services.

Studying Maine’s implementation of this pilot program, my collaborators and I found that it helped facilitate access to UI benefits among communities that had historically low take-up rates. These partner organizations helped their clients receive benefits faster, with fewer delays, and their clients reported less stress in the application process compared to similar workers who were not served by navigator partners. The navigators also helped raise issues and problems experienced by their clients to the state UI agency so that agency staff could address them—such as broken websites or the need for particular translations. Equally important, working with experienced intermediaries enhanced participants’ sense of their own efficacy. As a result, benefit recipients served by the navigators in Maine were more interested in joining worker organizations and undertaking collective action at their jobs when re-employed. What we saw was a virtuous cycle: Worker organizations, including unions, helped workers access much-needed economic assistance; those workers became more likely to see the role of government in their lives; and, by interacting with worker organizations, assisted workers became more interested in joining those groups to build collective economic and political clout.

Looking beyond Maine, I found evidence in my national survey of unemployed workers that those who received assistance from worker organizations or legal-aid clinics were similarly more interested in collective action. The relationship between assistance from worker groups and interest in workplace collective action held up across partisan and ideological lines: Democrats, Republicans, Independents, and workers with no partisan leaning were all more likely to be interested in collective action when they received help from worker organizations. These efforts, if scaled, can help promote a virtuous cycle of trust, engagement, political power, and voice: Greater worker political voice can help improve the UI system (and other state labor policies), which in turn supports further organizing to build collective worker voice and organization, crossing traditional partisan lines and scrambling traditional partisan allegiances.

The lack of participant engagement in UI is not an exception in the American safety net. Parallel research I have done on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides food assistance to low-income families, documents that only a small minority of SNAP applicants had ever been asked about their experiences with the program by government agency staff. Fewer still have reached out to agencies to share feedback. Only 20% of SNAP applicants in a survey I conducted in 2024 reported sharing their opinions or experiences with government staff. That same survey identified the importance of community-based organizations in facilitating such contact: SNAP applicants who reported being part of a local organization working on food-assistance issues were over 40% more likely to report contacting government agencies to share their experiences compared to SNAP applicants who did not report membership in a community-based organization.

Baking more opportunities for feedback and consultation into the design and implementation of policies doesn’t just help them function better. Such strategies also help make hard-won policy enactments visible and tangible to voters while building collective voice and power. My own research suggests that the lack of such organizing opportunities is one important reason that the Biden-Harris administration failed to register with voters. Voters went to the polls without feeling a personal investment and connection to the extensive set of policies the administration had enacted, or worse yet, attributed the benefits of Biden-Harris policies to others.

That’s consistent with other work tracking how voters experienced the Biden-Harris economic agenda. For example, important research by David Madland has shown that workers who were directly benefiting from historic investments that the Biden-Harris administration made in supporting electric vehicle (EV) battery manufacturing at the Blue Oval facility credited private-sector companies, not the administration, for their high-quality new jobs. Unlike on a construction project, the tax credits, loans, and subsidies that benefit private-sector companies are often invisible to voters unless trusted community intermediaries like unions or other worker organizations can help voters connect their own life circumstances back to government decisions.

The assumption that most people readily draw connections between policy and outcomes was one of the fatal flaws of the Biden administration’s approach to policymaking. In a chaotic information environment exacerbated by deep political polarization, citizens’ ability to make sense of government actions and draw conclusions about how they themselves are benefiting has only become more difficult. In this challenging political climate, the earned trust of civic organizations is a powerful currency that state governments have the opportunity to spend.

State legislators should build on models like the UI program navigators, and consider similar approaches to formally partner with community-based organizations to help their residents access social programs and, critically, build their collective economic and political voice through creative “hooks and levers” that engage intermediary groups. Such programs could include the model used in Maine, where the state gave funding and access to local organizations to help enroll individuals in social services and training opportunities, identifying and addressing barriers to accessing UI, and collecting relevant data on UI issues.

There are other promising models that states might explore as well. For example, states could create standing task forces or councils that include members of civic organizations with experience interacting with different government programs to incorporate their perspectives on an ongoing basis into policy development and program implementation. To be effective, however, these task forces or councils cannot simply be ceremonial or window-dressing; they need to commit to addressing the issues their members face, demonstrating clearly how feedback was used, and ensuring that members and their organizations are compensated for their time (as Washington state has done). States must also make sure they are tapping groups that have meaningful bases of members in the populations that policymakers want to engage.

Another alternative involves using agreements around government contracts or procurement to build ongoing community input and voice. Community benefits agreements are an important tool that organizations can use to negotiate legally binding agreements with contractors and government agencies who are funding those contractors. These agreements can be used by local communities to ensure that large development projects support their priorities—such as commitments to hire local workers for the project, setting wages and benefits to ensure quality jobs, and requiring certain uses of projects. They can also be a powerful tool for organizing communities and building an ongoing collective economic and political voice. State governments can support such agreements by encouraging or incentivizing their use.

A final model involves not just financing community-based organizations or encouraging their growth, but also supporting the development of expertise within those organizations to organize their members and engage with government agencies. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency’s Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers Program, launched under the Biden-Harris administration and defunded under the Trump-Vance administration, sought to support the development of technical capacities to engage with government in communities most affected by environmental justice concerns (such as persistent pollution or poor air or water quality). A similar approach was piloted by the Department of Energy through its RAMP fellowship program, which sought to support the development of local leadership and expertise to negotiate benefit and workforce agreements around federal energy investments. Although the federal government is no longer funding these efforts, they could be modified, scaled, and replicated at the state level.

No single model on its own is likely to be sufficient to build community voice and foster greater trust in government and democracy. But by experimenting over time, state legislators can build a base of evidence about the strategies that work best for specific policies and communities.

As state lawmakers experiment with these strategies, it will be essential for them to ensure that they are prioritizing support for organizations that represent a real base of members—and not just proliferating the mass of “bodiless heads” that characterizes so many interest-group formations on the political left. Constructing the kind of power-building effects that I describe in this piece will require organizations to have genuine connections to their bases, ideally through meaningful membership. Groups that merely engage people online with one-way emails or texts, or other cursory interactions, are unlikely to do a good job of communicating to the public what the government is doing, let alone building durable relationships that can engage people in politics and build collective power. Unions have, at their best, provided such structures to workers through a meaningfully democratic internal structure. But given labor’s current weakness, we need to experiment with more models of mass-membership organizations—and state governments could help jump-start that experimentation.

Incorporating and strengthening the voices of workers and groups that represent them in authentic, mass-rooted organizations will be especially important now as states step up to address the devastating cuts the Trump-Vance administration is making to the safety net and consumer, labor, financial, and environmental protections. Given the deepening crisis of democracy that we face, the stakes for rebuilding collective power and trust in government could not be higher for state legislatures.

About The Author

Alexander Hertel-Fernandez is the Herbert H. Lehman Professor of Government at Columbia University. He studies the politics of policy design, labor policy, and American political economy. He previously served in the Biden-Harris Department of Labor and Office of Management and Budget.