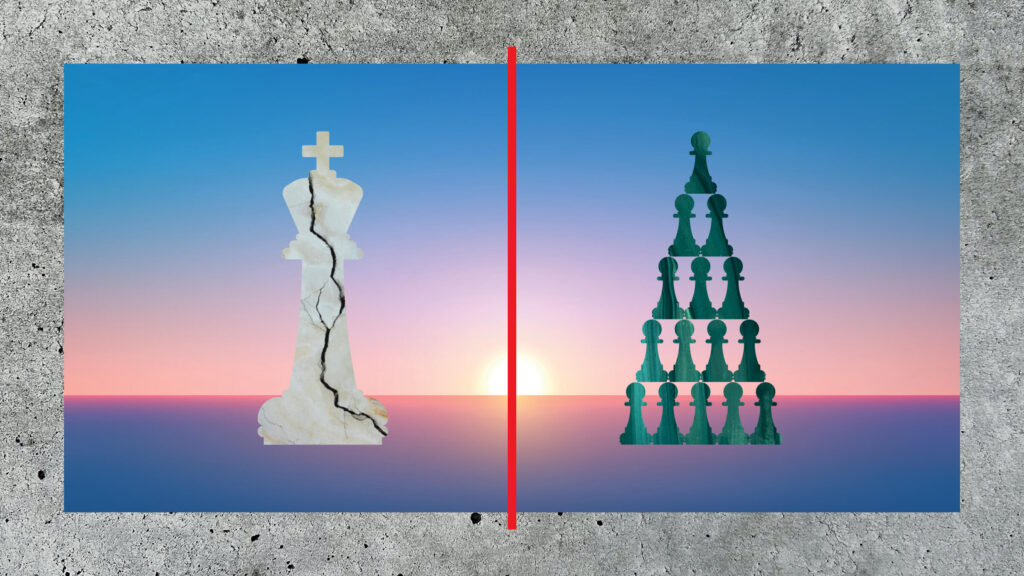

A Service Program Made for these Fragmented Times

Why states should lead the effort of enlisting young workers with a Civic Job Guarantee.

- By Andrew Doty

America turns 250 this year, and the state of our union is bleak.

Trust in the federal government has flatlined at just above 20% for decades. Partisan polarization has hardened into mutual disgust. Pride in being American has fallen to near-record lows, especially among the young.

For young adults, this disconnection is visceral. The average twentysomething has experienced national life as a long string of crises and disappointments: 9/11, the Iraq War, the Great Recession, COVID, and countless hashtag movements that have rarely produced real-world change. It’s no wonder that nearly half of them chose to roll the dice on President Trump’s tear-it-down populism in 2024.

The establishment response has been predictable: National service will fix this. Figures such as retired General Stanley McChrystal, Senator Chris Coons, and former Secretary Pete Buttigieg have all argued that shared service can restore trust and civic cohesion. As California Governor Gavin Newsom recently put it, “We’re all exhausted, polarized, traumatized…. That’s why I believe in national service. It should be compulsory.”

But this logic is backwards. The very conditions driving elite enthusiasm for service—polarization, collapsing trust, declining patriotism—are precisely what make traditional service policy politically fragile. In a low-trust society, asking young people to sacrifice for abstract national ideals at poverty wages isn’t inspiring. It’s tone-deaf.

AmeriCorps’ quiet near-gutting in 2025 proves the point: Under polarized, low-trust conditions, traditional federal service models just cannot muster the political capital needed to defend themselves.

A new era of national service that fits the national condition is likely to begin not in Washington, but in state capitals, with a model closer to a guaranteed civic jobs program than a traditional service fellowship.

A (theoretically) beloved institution under fire

For three decades, AmeriCorps has been the flagship of domestic national service. Born in 1993 during a period of post–Cold War optimism and signed into law by President Bill Clinton, it expanded steadily under Republican and Democratic presidents alike. Its inaugural class of roughly 20,000 participants has grown into more than 1.25 million alumni who have served in all 50 states.

The program’s purpose is captured simply enough in the AmeriCorps Pledge: to mobilize young people to “get things done for America—to make our people safer, smarter, and healthier,” to “bring Americans together to strengthen our communities,” and not just during their time of service but for years to come.

On paper, the idea remains popular. Nearly 90% of Americans say they support voluntary national service, and a majority say they believe a more robust national service program would help bridge political divisions. AmeriCorps should be a rare bright spot in American public life, as cherished as the military or the National Park Service.

Yet last April, the Trump administration nearly succeeded in gutting it. The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) ordered the cancellation of roughly $400 million in AmeriCorps grants—over 40 percent of the agency’s annual grant funding—affecting more than 1,000 organizations and over 32,000 members and volunteers. More than two dozen Democratic-led states sued to block the cuts, and a federal district court ordered the restoration of defunded grants in those states.

What is striking is not only how close AmeriCorps came to collapsing, but that it was saved only through partisan legal efforts. Despite 30 years of bipartisan rhetoric and favorable polling, the attempted defunding of the nation’s primary nonmilitary service program generated little broad-based public backlash.

The explanation lies less in AmeriCorps’ quality than in its fit with contemporary America. In a country shaped by polarization, low public trust, declining patriotism, and a large cultural gap between progressive institutional culture and the public, AmeriCorps is structurally ill-equipped to survive.

The conditions any service model must confront

Any viable service policy today must survive four conditions that now define American public life.

1. Polarization

Americans increasingly view their partisan opponents as dishonest, unintelligent, and immoral. Policies and institutions that once garnered bipartisan support now come under scrutiny from one side or the other as they are coded “red” or “blue”.

AmeriCorps began as a bipartisan experiment but gradually came to be coded as left-leaning. The 2017 Trump budget proposal to eliminate the Corporation for National and Community Service signaled the shift outright. Although Congress then rejected the cuts, it was only a matter of time before AmeriCorps was back in the crosshairs—an expendable symbol of “big government” rather than a shared civic institution worth defending.

Polarization doesn’t just make it impossible to pass new federal service legislation. It makes defending existing service institutions contingent on who holds power. If a program lives in Washington and is coded as blue, it is always just one election away from an existential threat.

2. Collapse in public trust

Americans’ trust in the federal government has been in a slump for decades and is especially low among the young adults AmeriCorps has tried to engage since its founding.

AmeriCorps’ structure exacerbates the trust problem. Its funding structure is complex and multilayered: Money flows from Congress to a federal agency, then to state service commissions, then to nonprofit intermediaries, and finally to individual host sites and members. Its work, while valuable, is largely invisible to the average American: tutoring struggling students, serving seniors, helping food banks, doing casework after disasters. In an age of federal distrust, this complexity kills its credibility.

3. Declining patriotism

National service programs presume a level of attachment to a national “We” that is far weaker today than it used to be. The share of adults who describe themselves as “extremely” proud of being an American is at near record lows. And young adults are the least likely age group to describe themselves as “very patriotic.”

Americorps is designed to draw on a spirit of national volunteerism: Rather than being paid a competitive salary, service members receive a modest stipend, an education award, and the moral satisfaction of service. But young adults today—especially working-class young adults—are more skeptical of calls to sacrifice for abstract ideals. “Serve your country” is not the motivator it was in the early 1990s.

4. Progressive cultural disconnect

Finally, there is a cultural disconnect. Frequently, the bureaucratized institutions that manage service programs and nonprofits that deliver services reflect highly educated, progressive, urban-professional norms. This culture, with its own language, values, and aesthetic, not only attracts a limited range of participants but can also alienate the people it claims to be committed to serving.

AmeriCorps’ selectivity compounds the problem. With an estimated three to five applicants for every AmeriCorps service opening in the 2010s, there are far more young people interested in a year of serving others than there are available AmeriCorps slots. The result is a semi-elite corps of “service people,” drawn disproportionately from collegiate and civically engaged circles, serving populations who are often quite unlike them.

These four conditions mean that a complex, federally administered, nonprofit, service-forward model is poorly matched to the country as it exists today.

If national service is to survive and matter in 2026 and beyond, it must be rebuilt from institutions that are closer to people’s lives, more culturally flexible, and more trusted than the bureaucracies of Washington, D.C.

All of this points to the states.

States as the stewards of a new service era

In contrast to the top-down model of AmeriCorps, states are in a position to lead the next era of American service policy from the ground up on every issue identified above.

Polarization. Relative to national service, state-level programs can be more readily framed around concrete, less ideologically freighted needs—wildfire mitigation, remediating abandoned properties, or helping neighbors to navigate government paperwork at the public library.

Public trust. Americans consistently express more confidence in state and local government than in federal institutions. States also administer the systems where labor shortages are most acute and where people interact most regularly and directly with the government: public health, education, infrastructure, and more.

Patriotism. If national belonging feels distant to young adults, they may be more ready to engage in service close to home, where friends, family, and former and future classmates live. At the state level, the call sounds less like “serve your country” than “fix your community.”

Progressive disconnect. States can design, brand, and administer service programs to match local culture and avoid unhelpful ideological coding. Utah Governor Spencer Cox, for example, has emphasized that he was able to build support for service policy in a very conservative state by not “left-coding” it, unlike the Biden administration’s now-defunct American Climate Corps.

Several states have begun experimenting with state-level service models in recent years. From Maryland’s first-in-the-nation, full-time paid Service Year Option now enrolling hundreds of high school grads annually, to Utah’s One Utah Service Fellowship, which combines state, private, and federal resources to offer young adults a stipend to complete up to 1,700 hours of community service at a fraction of the typical state investment, their models differ in philosophy and design. Still, these programs remain small relative to the scale of need. Each enrolls hundreds or thousands, not tens of thousands. None has yet created a constituency capable of defending the programs should it later face DOGE-level cuts.

If states are going to meet their service potential, their policies need a bolder design.

The case for a Civic Job Guarantee

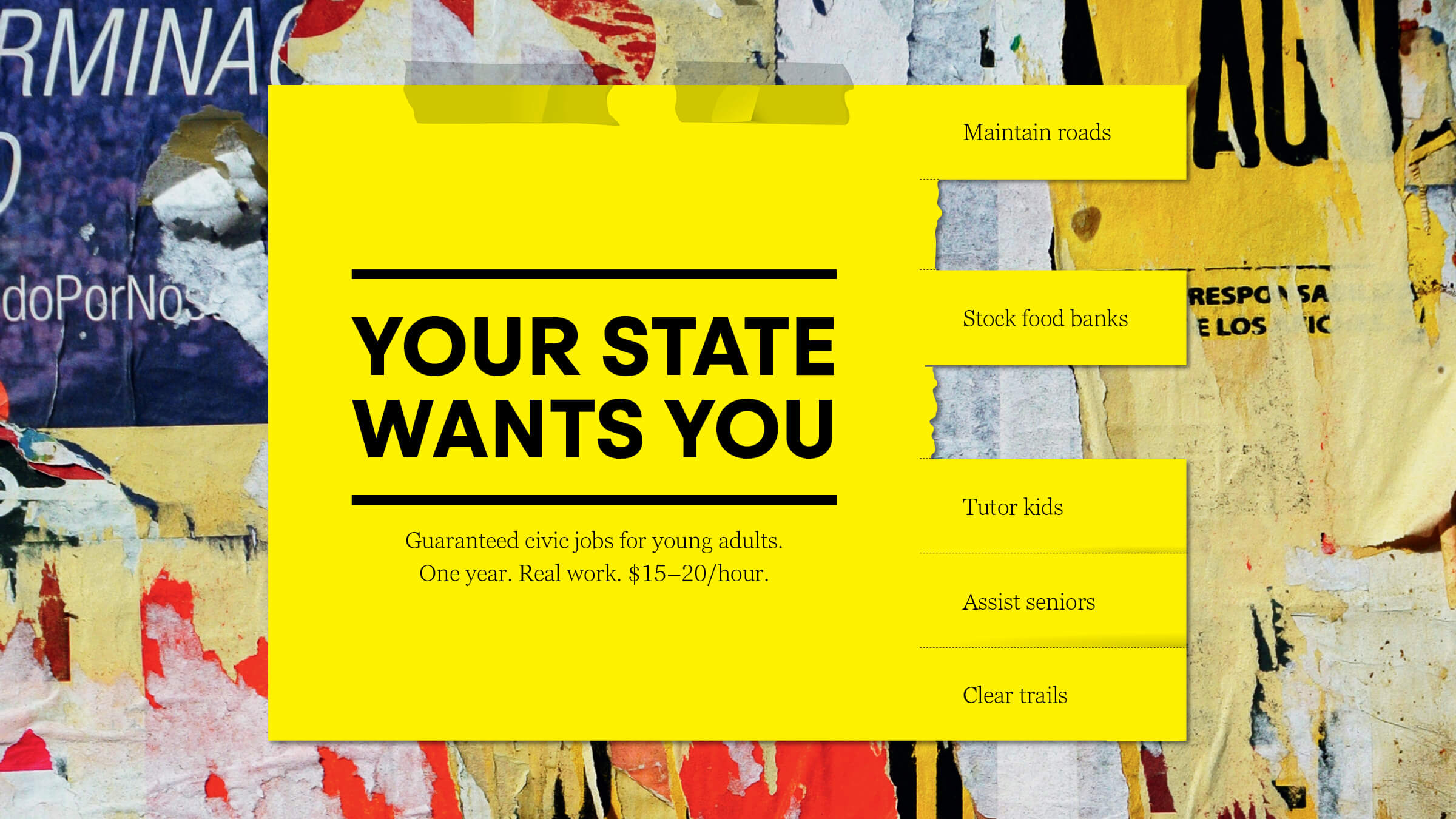

An ambitious state could go further: Guarantee that any young adult who wants one year of full-time civic work can have it—at a fair wage, doing visible, productive, nonpartisan work as a state employee.

Call it a Civic Job Guarantee: national service translated into the social contract for our times, not a call to sacrifice for some abstract nation, but an offer of dignified work that benefits both workers and their communities.

Every piece of this offer is intentionally crafted to meet the public where they are, not where service advocates wish they were.

Young adults would fill only straightforward needs the public broadly recognizes as legitimate: conservation crews cleaning up mountain trails, support teams listening to the elderly in retirement homes, construction crews hammering away on public infrastructure projects, and free after-school tutoring to any child who wants it. To ensure the work has broad buy-in, the oversight board should include bipartisan representation from labor, civil society, and private-sector stakeholders.

A “state hires you directly” approach would ensure accountability to the state’s voters, reduce the needless administrative overhead of various intermediaries, ensure consistent public branding, and avoid entanglement with the cultural norms of nonprofit organizations.

Many young adults who feel that they owe their country little are open to work that pays at least the state’s minimum wage (or ideally a living wage) and offers on-ramps to future employment in well-paid fields like healthcare, the skilled trades, and the military. This is a more broadly accessible and reciprocal offer than the traditional moralized call to serve for a stipend. And as AI automates entry-level private sector jobs, the value of structured public work experience will only grow.

Calling it a “job” also signifies that it is real work: valuable and strenuous. The program’s legitimacy depends on whether the public considers these positions “voluntourism,” “make-work,” or, rather, as a means of addressing critical public needs in a way that earns its pay. Because the offer is less a handout than a hand up, it’s less likely to trigger right-of-center voters and harder for populists to oppose while staying on message.

A guarantee turns a beneficial program into a durable one. If any young adult can opt into a one-year paid civic job, the program creates a constituency ready to defend it, enlists a network of indirect stakeholders from parents to universities, and has the chance to become a near-universal cultural rite, like learning to drive a car.

But is it affordable? A better question is whether states can afford the current fragmentation of spending on unemployment, workforce training, service policy intermediaries, and programming for disengaged young adults. One 2020 analysis cited by AmeriCorps found that every dollar of federal taxes invested in national service returns $17 in benefits through increased lifetime earnings, higher tax revenues, reduced crime, better health, and improved educational outcomes. A state-run model could capture many of these benefits with lower overhead.

The greater risk is timidity. As we have seen from President Trump’s unfulfilled promise to get Mexico to pay for a border wall and Mayor Mamdani’s unrealistic policy commitments, voters are forgiving of elected officials they view as being “wrong” in the right direction. What they punish is the absence of ambition.

Declaring a Civic Job Guarantee, even as an aspiration, reframes service from a nice-to-have program for select moral do-gooders, to paying young Americans to do valuable work for their communities.

Repairing the national fabric from the state level up

Political divides narrow when people from different backgrounds work side by side on shared projects under conditions of relative equality. A year spent clearing floodplains or tutoring elementary schoolers alongside someone who voted differently does more to humanize disagreement than any exhortation from an elected official. Public trust grows when residents see their states hire young people, deploy them competently, and leave visible improvements in parks, schools, and streets.

National service has always been compelling in the abstract. The challenge now is to build a version that fits the country we have. States are best positioned to do that.

A Civic Job Guarantee—state-run, nonpartisan, strenuous, universal, and fairly compensated—would align the moral promise of service with the contemporary economic and cultural realities of the young adults it is designed to engage. It would create a durable constituency, visible public benefits, and a generation of Americans more ready and willing to contribute to their country.

States should give their people the chance—and the job—to build that future.

About The Author

Andrew Doty is a Washington, D.C.–based consultant focused on civic reform and democratic governance. He advises the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation & Institute’s Center on Civility and Democracy and has worked with numerous democracy-focused nonprofits, including Democracy Notes and Protect Democracy.