Federalism as a Style of Combat

Traditional federalism concerns procedures and norms. As the Trump administration and red states engage in asymmetrical war, it’s become a necessary means for consolidating power.

- By Arkadi Gerney & Sarah Knight

Over the past year, President Trump and his allies have enriched themselves and entrenched their power—all while locking out (or seeking to lock up) their political opponents. Anyone paying attention recognizes that the institutional landscape of the United States has shifted in ways that make 20th-century assumptions about national-level guardrails increasingly obsolete.

Those outmoded assumptions include a misplaced confidence that the separation of powers baked into our federal structure will prevent one branch from dominating the others. In the past year it has become clear that the traditional horizontal checks and balances that might have constrained an autocratic executive branch are failing.

While lower federal courts have often acted as a temporary halt on Trump initiatives, their decisions are regularly being overruled by a mostly compliant Supreme Court—a stratum of the judiciary that has concentrated its own power at the expense of district and circuit courts via its shadow docket and a recent barring of most nationwide injunctions.

Meanwhile, on Capitol Hill, Republicans have shown themselves eager to cede power, including Congress’s constitutional spending power, to an executive bent on hoarding it. So far, Democrats in Congress have struggled to remain unified enough to leverage what little power they have to mount a durable challenge, even as they have tried with last November’s shutdown and more recently the effort to rein in ICE by withholding funding for DHS.

These limp horizontal checks underscore the importance of the vertical checks of federalism and state power on an increasingly autocratic president. Over the past decade, growing ranks of scholars have revived an old idea: namely, that federalism can be a bulwark for democracy.

As its name conveys, the United States is an invention of states: Thirteen newly independent states created our country and our constitution. In Federalist No. 51, Madison proposed state governments as a “double security” against a potential autocratic federal government—a concept that lives on in our constitutional structure.

At one level, state power has been at the heart of some of the greatest rifts to threaten our democracy: the Civil War, and a century of Southern state defiance of civil rights. But, if the centuries-old tensions among states and between states and the federal government are a source of our deepest national scars, we contend that the distinct features of federalism also explain much about the useful redundancies, resilience, and durability of American democracy.

In our view, state power is an essential asset—and the most important strategy—in the effort to counter autocracy in the United States. Our case draws from the academic literature, comparative research, political rhetoric, and what we’ve seen from the track record of state government leaders to date. But we believe that the challenges of the present moment require a more expansive, flexible, and aggressive articulation of the connection between federalism and democratic resilience than the current literature typically provides.

The academic argument often proceeds cautiously. The story goes something like this: Federalism can help resist national autocrats under certain conditions; decentralization creates redundancy, which may slow democratic backsliding; and the democratic experimentation that happens at the state level can contribute to overall democratic resilience.

All true. But none of that fully captures how federalism can and must function in a country where political coalitions are sharply divided across states and where the effort to centralize power at the national level has never been greater.

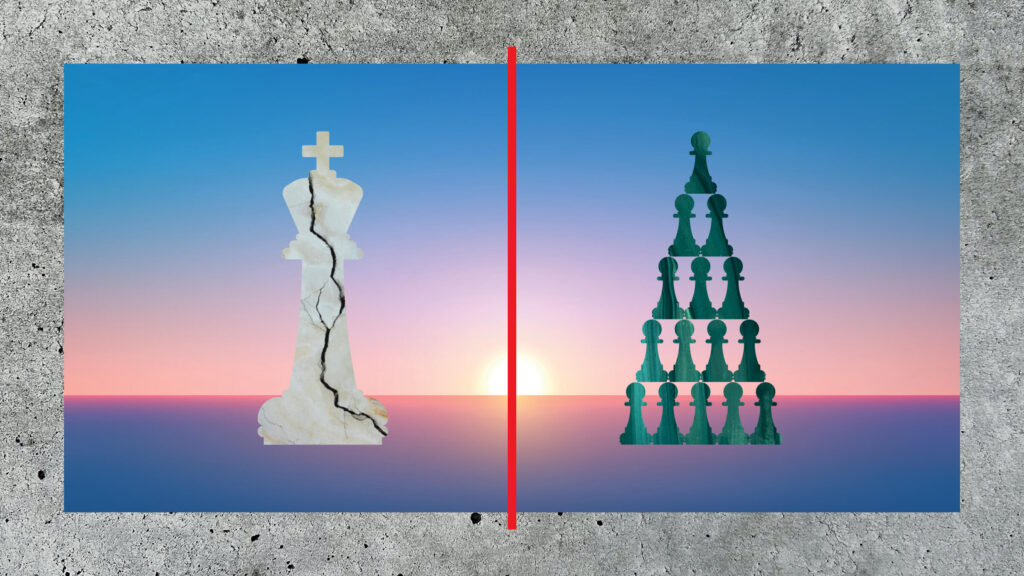

Our conception of federalism as a bulwark for democracy expands on and departs from the traditional literature in two ways. First, we see federalism as a style of anti-authoritarian combat rather than merely a set of rules and veto points; second, the health of a democracy that a federalism strategy might preserve is best measured by the accumulation and deployment of countervailing power, not by the preservation of a procedural checklist.

If the first point of departure imagines federalism as a more aggressive, dynamic means for democracy defense, the second offers a revised conception of the democratic ends federalism might successfully preserve.

We believe that the dispersion of power and the maintenance of the potential for political competition is more important to the survival of democracy than the presence or absence of particular rules and norms. And we believe that, with an autocratic takeover of Washington at hand, that power to preserve democracy necessarily resides in the states.

1. Harnessing federalism as a style of anti-authoritarian combat

If one compares the battle for power in the United States today to armed conflict, the traditional case for federalism might be analogous to the Geneva Conventions: a legal framework to constrain combatants.

We think it’s more useful to think of federalism as a style of combat. Like insurgency or asymmetric warfare, a democracy defense strategy grounded in federalism is best understood as an attempt to leverage a range of decentralized, adaptive, unconventional tactics to challenge an opponent that controls the traditional levers of national government power.

The federalism literature tends to emphasize decentralization’s protective redundancy: If one level of government is captured, others remain. Academics have made this case in the context of U.S. elections, for example, noting that their decentralized nature makes it very difficult for a federal autocrat to seize total control of election administration. As we look at ways the 2026 elections might be manipulated for the purposes of consolidating power by an autocrat in the White House, there’s some comfort in the fact that an estimated 10,000 different state, county, and local officials administer the polls under a patchwork of federal, state, and local rules and requirements.

But this formulation implies a passive, reactive form of democracy resilience. A more muscular vision of federalism is one that embraces states’ ability to generate political friction, not merely absorb it. Put another way, democracy is not defended through state veto points alone; it is defended through state initiative.

Individually and collectively, the states represent an enormous reserve of power. States are where a substantial share of decisions about education, health, and safety are made. Collectively, state budgets totaled just over $3 trillion in revenue in 2023—only about a trillion less than the federal government’s. While federal debt exceeds $30 trillion, states collectively operate in the black, holding more than $4 trillion in investment assets (including in excess of $1 trillion of the federal government’s debt).

Much of that fiscal and political power is currently in the hands of united Democratic governments. Thirty-nine of the 50 states are currently controlled by one party via a “trifecta” (i.e., both houses of the state legislature and the governor’s office). Of these, 23 states are under unified Republican control and 16 are under unified Democratic control. While there are fewer blue trifectas, those 16 states have a disproportionate share of economic and government spending power: They collectively represent 46% of the nation’s GDP, compared with just 37% in the red trifecta states; and the collective budgets of blue trifecta states represent 49% of total state government spending, compared with just 31% in the red trifectas.

Why focus on the red-state/blue-state divide? For one thing, red trifecta governance is a fairly neat predictor for the specific style of authoritarianism we’re seeing emerge in the United States. In his 2022 book, Laboratories Against Democracy: How National Parties Transformed State Politics, political science professor Jacob Grumbach analyzed state performance along 51 indicators of democratic health. His analysis showed that states in which Republicans have dominated state government since 2000 have seen significant democratic decline—declines not seen in states with Democratic or divided control.

To understand the potential of state power to thwart federal power, one need only look to the times, places, and methods by which red states stymied the Biden administration.

The primary engine of the Biden backlash was red states leveraging their legislative, executive, legal, political, and fiscal power. Take Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s migrant busing strategy, which effectively nationalized the immigration debate and upended the politics of blue states. Red states also unleashed a wave of financial coercions that targeted Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives, pressuring corporations to back off commitments; this set the tone for the Trump administration’s campaign of corporate capitulation. And red-state attorneys general coordinated lawsuits attacking virtually every Biden policy, on every possible front, substantially undercutting many of the administration’s major initiatives.

We should pay close attention to how red states activated their powers to advance their policy agendas and, more important, power-enhancing goals. First, they emphasized collective action and extraterritorial aggression. From abortion travel bans to the “anti-woke” corporate pressure bills and migrant busing operations, a great number of red-state initiatives have been explicitly designed to coerce and compel activity beyond the borders of the origin states and disrupt the governability of blue states.

While there are nascent efforts by blue states to operate more aggressively, they don’t yet match the bold, multifaceted, well-resourced, kinetic intensity of their red-state counterparts. Blue states have, for the most part, used federalism to mount a defense of a prior status quo, arguing for it in the context of protecting their own state’s sovereignty. But the asymmetric and power-consolidating nature of red-state federalism suggests the potential of a blue-state counteroffensive that explicitly seeks leverage in the contest for national power. That counterattack could be a critical source of power to fight authoritarianism.

2. How to measure the success of a federalism strategy

In recent decades, democracy advocates have developed what we might call the democracy checklist: a well-intentioned catalog of procedural norms that supposedly signify a functioning democracy: independent redistricting commissions; nonpartisan election administration; judicial restraint; the depoliticization of state courts.

These indices of norms and safeguards may make sense as a framework to measure the relative health of democracy on a country-by-country basis, or the changes within a particular country over time. But as a prescription for how to safeguard democracy through federalism, such procedural checklists can point democracy advocates at exactly the wrong strategy: An unswerving preference for applying universal norms across a range of states may lead to unilateral disarmament.

For many years, universal aspirations like these were not just noble, they were plausible. The second half of the 20th century aligned generally with an era in which both parties accepted (rhetorically, if imperfectly in practice) that political power should be structured through largely neutral institutions, and that each side’s long-term interest was best served by mutual restraint. But checklists like these only make sense in environments where all actors agree to play the same game.

The summer of 2025 delivered an object lesson in the risks of asymmetrical attachment to the rules. At the insistence of President Trump, Texas Republican state lawmakers took the extraordinary step of redrawing election district lines mid-cycle to add five seats to the narrow GOP advantage in the U.S. House of Representatives. Rather than roll over, Texas’s Democratic lawmakers fled the state to deny a quorum and delay the adoption of new maps. They then took their case to Illinois and California, arguing that the redistricting shenanigans in Texas threatened the balance of power everywhere. In response, California Governor Gavin Newsom spearheaded a successful ballot measure to temporarily pause California’s independent redistricting process and approve maps that offset Texas’s gains. As more red states move to redraw their lines, more blue states like Virginia are countering.

In the redistricting fight that exploded last summer, Democratic leaders finally coalesced around a strategy of fighting fire with fire. That put enormous pressure on organizations with a mission to protect small-d democracy. Take, for example, Common Cause, a venerable watchdog group that has advocated for independent redistricting commissions and other reforms aimed at ensuring that nonpartisan goals inform districting. Their efforts succeeded in enshrining “safeguards” in some blue and purple states but left red states largely unconstrained. This meant the independent-commission states were especially vulnerable to Donald Trump and Texas’s 2026 redistricting scheme. Weakness invited aggression. Even as Governor Newsom began sharpening his sword, Common Cause continued to advocate for a strict adherence to process that would have had California waving a white flag—that is, until a wave of board resignations and financial pressure forced the organization to backtrack and adopt a neutral stance on the counterattack.

California’s redistricting counterpunch was not an abandonment of democratic values. It was the protection of democratic viability. It was the recognition that in a world of asymmetric hardball, restraint by one side alone is not a virtue—it is surrender.

In late 2025, when a group of Republicans in Indiana’s legislature defied President Trump and voted down a plan to gerrymander the state mid-cycle, it was properly read as a profile in courage and a step back from complete “nuclear” escalation of the redistricting wars. But we also read that episode as a marker of success for blue-state counteraggression and deterrence. California’s demonstrated capacity for retaliation—and the credible threats from other states to join suit—created the condition where Indiana’s defiance of Trump became more possible and more likely. In short, if the end goal is national nonpartisan districting, the only reasonable way to currently achieve that is through deterrence with the threat of mutually assured electoral destruction. Exercising countervailing power is the necessary prerequisite for creating the conditions for compromise.

In the redistricting context, and in many other contexts, too, the federalism lens clarifies that democratic resilience is not about preserving neutral processes; it’s about building sufficient countervailing power to deter, constrain, or neutralize antidemocratic aggression. This mindset means a shift away from assessing the health of our democracy based on the purity of its processes today, and toward an analysis that asks how likely those processes are to contribute to a plausible, competitive, pluralistic, contestable democracy tomorrow.

This represents a culture shift for both big-D and small-d democrats. Liberal elites have only episodically and half-heartedly embraced muscular visions of federalism. They’ve poured greater energy into securing rights, freedoms, empowerment, and a decent life for all Americans; a states-first strategy is antithetical to some of those noble universal values. But a growing cadre of academics—Erwin Chemerinsky, Aziz Huq, Jacob Grumbach, Miriam Seifter, Richard Hasen, David Pozen, Joseph Fishkin, and Jessica Bulman-Pozen—are eschewing simple proceduralism and, to varying degrees, embracing once-heterodox muscular visions of federalism. More importantly, 2025 saw more state leaders, like Illinois Governor JB Pritzker, adopt a pugilistic style of counteraggression to challenge federal overreach and assert state power in realms beyond redistricting.

A practical, actionable path forward

So, what does all this portend for 2026, and how should state leaders who care about democracy use state power to defend it?

If 2025 revealed the contours of asymmetric constitutional combat, 2026 must be the year of counterattacks in favor of democracy. The question is no longer whether federalism can serve as a bulwark; it’s how aggressively, creatively, and collaboratively states are willing to wield state power to disrupt and destabilize in defense of democracy itself. Below, we outline three concrete areas where state leaders who care about democracy should seize the initiative this year.

1. Use state economic power as a strategic lever

In 2025, we saw President Trump leverage federal spending power to coerce capitulation from universities, businesses, countries, and states. But with several trillion dollars in aggregate pension fund and investment assets and hundreds of billions in annual procurement contracts, blue trifecta states have enormous countervailing power. They should use it and be creative in identifying other economic leverage points in their arsenals, such as state insurance regulation. In all major lines of insurance—life, property, health—actuarial risks are concentrated in red states.

Consider life expectancy: Blue-state residents can expect to live an average of 77.8 years, compared with the 74.7-year expectancies for red-state residents. Despite these differences, insurers tend to smooth differing risk profiles across state lines. More active state insurance regulation can help blue states stop subsidizing red-state risks, particularly where those risks are driven by red-state policies, such as the failure to expand Medicaid. There is no reason blue states should allow premiums paid by their citizens to subsidize payouts for early deaths driven by red-state policy failures, like weak gun laws that give criminals and the mentally ill easy access to firearms, or the failure to expand Medicaid access. Forcing red-state insurance premiums to account for state-based risks like those would create an additional financial incentive to address them.

2. Create state-level protections for contestable democracy

Redistricting has shown us how fighting fire with fire can protect the contestability of elections. But Trump’s efforts to leverage federal power to rig the 2026 elections go far beyond redistricting. His March 2025 executive order purporting to protect election integrity seeks to interfere in state processes by imposing federal requirements on voter-roll verification, election machinery, and valid time frames for accepting ballots.

In the fall of 2025, Trump’s DOJ sent election monitors to California and New Jersey, raising concerns that he may send law enforcement or military “observers” to oversee the 2026 elections. More recently, the president has spoken of “federalizing” elections, suggesting he envisions further intrusions into what is explicitly a state and local prerogative. With these threats in mind, states should adopt “democracy shield” laws that trigger automatic responses to federal and state manipulation of elections or certification—including new state-level civil rights causes of action for voters who find themselves targeted by federal actors, and emergency election administration authorities that can be vested in governors or secretaries of state. These mechanisms can both harden states against possible federal interference and create deterrence against aggressive state-level manipulation elsewhere.

3. Expand state investigatory and enforcement capacity for federal abuse and corruption

In 2025, state attorneys general were highly coordinated, filing more than 100 challenges to the Trump administration and notching significant preliminary wins that constrained the administration’s unlawful actions, including those relating to withholding money from states.

In 2026, the best defense might be a good offense. While a federal court has dismissed the Trump administration’s indictment of New York Attorney General Letitia James, state attorneys general and local prosecutors should explore how to hold rogue federal officials accountable for state law crimes. With masked ICE and CBP agents grabbing people (including, increasingly, misidentified American citizens) off the streets; with corporations and administration insiders engaged in bribery schemes to negotiate favorable deals with federal regulators in violation of federal and state antitrust and consumer-protection laws; and with financial fraudsters unpoliced by a compliant SEC and a disemboweled Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, states need to leverage their criminal and civil authorities to fill the gap and backstop the rule of law.

This includes taking intermediate steps toward legal action, like Minnesota’s criminal investigation of ICE and CBP’s two killings in that state in January and Illinois’s Accountability Commission, established last fall to create a record of abuses during the federal occupation of Chicago. These records could be used to prosecute individual wrongdoers in the future. The specter of liability tomorrow can create a measure of deterrence today.

There is no silver bullet, but an insurgency of state power can deliver autocrats a political death by a thousand cuts. Each of these actions rests on the same insight: Democracy must be defended with state power—accumulated at the state level, deployed aggressively, and coordinated across borders.

In 2026, if state leaders truly believe we are in an existential battle for the fate of democracy, they need to fight like it.

About The Authors

Arkadi Gerney is a strategist who advises state leaders on democracy resilience. He founded and led The Hub Project, managed the advocacy arm of the Center for American Progress, and served under New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg managing the Mayors Against Illegal Guns coalition.

Sarah Knight helps state leaders and organizations develop strategies for democratic resilience. She previously directed the U.S. Democracy Program at Open Society Foundations and led the field program at the American Constitution Society.