Firebreak Federalism

The U.S. Constitution gives states the responsibility—and the tools—to counteract federal overreach

- By Harrison Stark

In January, the Century Foundation published the United States Democracy Meter, a new tool for assessing the health of our democratic system. Comparing the state of our institutions between 2024 and 2025, the report explained that “democratic collapse has already occurred” in the United States, finding a precipitous 28% year-over-year drop in democratic practices. This “sharp unraveling,” the authors concluded, has pushed the country “well into authoritarianism.”

Whether or not one agrees with that final assessment, there are mounting collective concerns over the health of our constitutional order. For the drafters of the Constitution, keeping tyranny at bay was an overriding imperative—so much so that scholars once lamented our founding document’s preoccupation with despotism as unhelpful or irrational “tyrannophobia.”

But at a time when both Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court have shown limited interest in reining in the executive, it is natural to wonder whether the Constitution’s structure is meeting the moment. In our era of hyperpartisan national politics, where there is often more separation of parties than separation of powers, are there still meaningful checks on federal overreach?

There are, and it is not too late to rely on them.

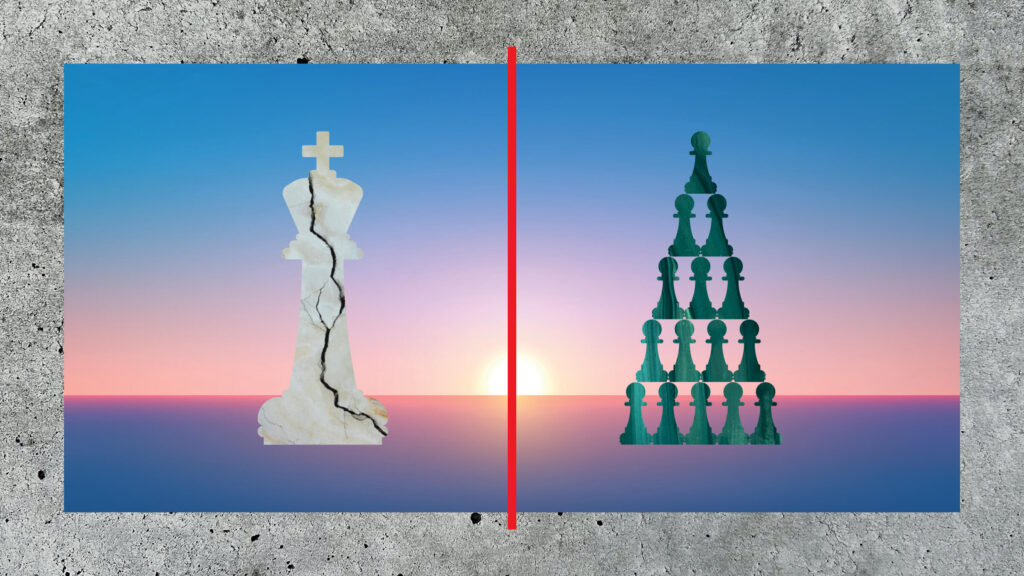

Horizontal, interbranch competition is only one species of checks and balances. Especially in moments of politically consolidated federal power, the Constitution’s structure offers another, potentially more meaningful safeguard: the states.

An antidespotic system

Academics, historians, and judges often opine on the liberty-protecting properties of federalism. But these aren’t just platitudes. Our vertical constitutional structure was designed to be antidespotic. Federalism’s premise is not just that power is less threatening when divvied up (though that’s true). Equally, the idea is that by diffusing lawful power between the state and national levels, our bifurcated system creates space for—and actively encourages—contestation between sovereigns that may not adequately self-police. One of federalism’s foundational goals is to empower the people to harness each level of government to push back on abuses by the other.

This is what James Madison meant when he referred to the nation’s “compound republic” as offering “a double security … to the rights of the people[:] The different governments will control each other, at the same time that each will be controlled by itself.”

Alexander Hamilton put it even more pointedly. Just as “the general government will at all times stand ready to check the usurpations of the state governments, [states] will have the same disposition towards the general government…. If [the people’s] rights are invaded by either, they can make use of the other as the instrument of redress.” Hamilton saw it “as an axiom in our political system that the State governments will … afford complete security against invasions of the public liberty by the national authority.”

In 2026, this premise—states as bulwarks of liberty—may sit uneasily with some. For many, any assertion of robust state authority vis-à-vis the federal government immediately comes up against the long shadow of unsavory historical episodes like “the Southern Manifesto” and coordinated state attempts to undermine racial equality in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education.

But rights-protective federalism has always been a two-way street. Just as the federal government stepped in to enforce the Constitution and dismantle Jim Crow apartheid—a form of domestic authoritarianism—states have played a critical role in ensuring their residents enjoy the rights guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution when the federal government overreaches or abdicates its responsibilities. In fact, for much of American history, when federal officials overstepped their legal authority, it was state law that provided a remedy for the constitutional violation.

Viewed in this wider historical lens, the idea of states checking the federal government takes on greater structural, as opposed to purely partisan, significance.

When states seek to keep the federal government within its constitutional bounds—acting, in Hamilton’s words, as “suspicious and jealous guardians of the rights of the citizens against encroachments from the federal government”—they are not necessarily just being obstructionist or unlawfully “resisting” federal authority. Often, they are embodying one of the oldest, and proudest, traditions of American federalism: guarding against the possibility of despotism.

States retain this power and responsibility today. Although the federal government often asserts that federal operations are “supreme” over state power, the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution is not a blank check for the federal government; in fact, it’s not “an independent grant” of authority at all.

Instead, the Supremacy Clause “simply provides ‘a rule of decision’” in instances of incompatibility: Where “federal law … conflict[s] with state law,” federal law wins out. But nothing in the Supremacy Clause authorizes the federal government to violate the Constitution nor diminishes states’ historical role in ensuring constitutional fidelity.

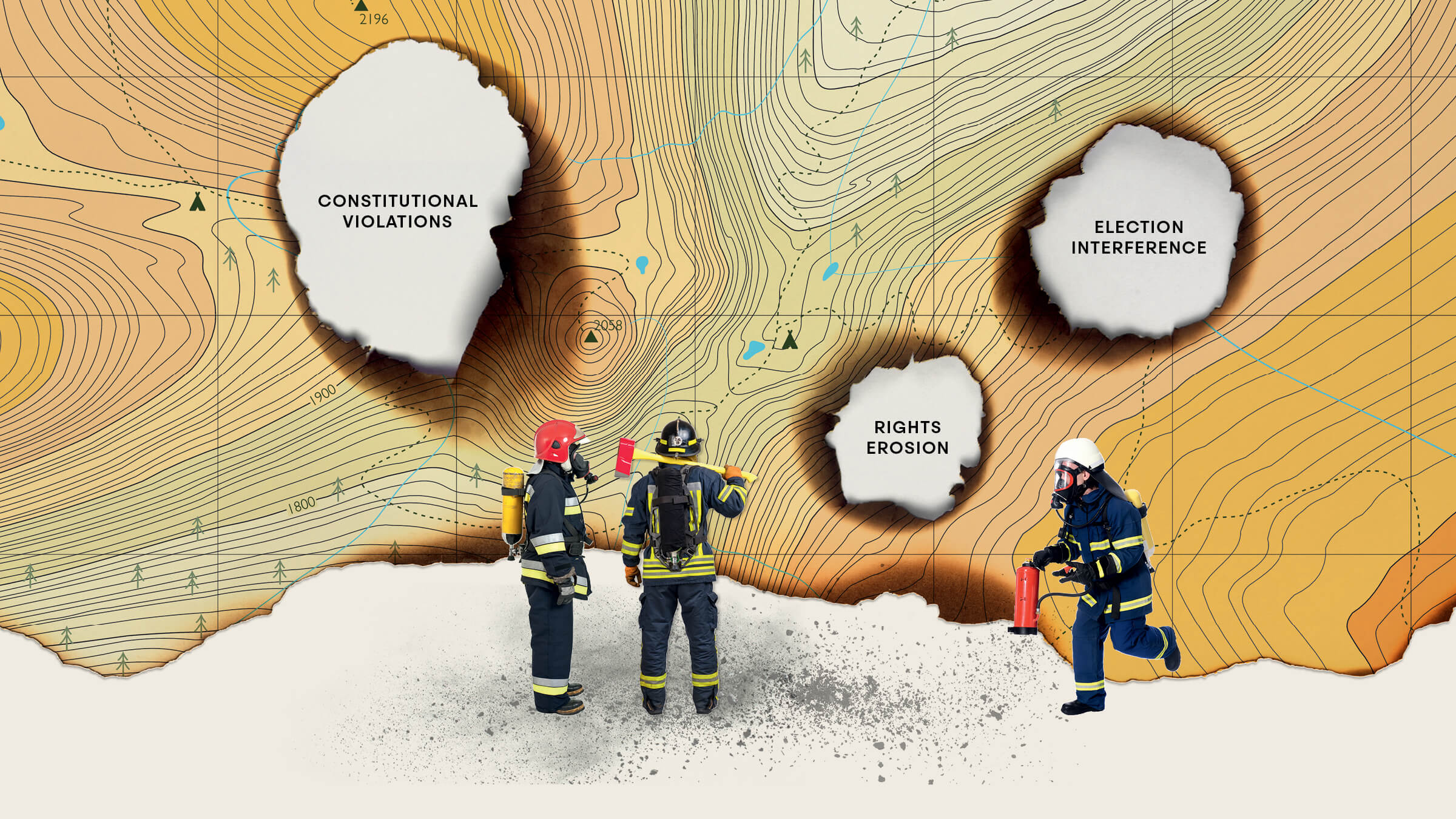

Today, state lawmakers and officials have powerful tools to fulfill their structural mandate and counteract constitutional violations by the federal government. In particular, there are at least four ways that states—and only states—can meet this moment and further federalism’s liberty-enhancing aims.

Safeguarding free and fair elections

Perhaps the most foundational element of liberal democracy is the people’s opportunity—through their votes—to choose an alternative political path. It is not an exaggeration to say that free, fair, and competitive elections are the backbone of a functioning democracy. For our constitutional system to work, elections must remain a viable—and trusted—mechanism for ascertaining popular will and ensuring that government truly operates by the consent of the governed. This is partially what political scientist Adam Przeworski was referring to when he memorably described democracy as “a system in which parties lose elections.”

Under the U.S. Constitution, responsibility for the weighty task of running elections falls chiefly to the states. Article 1, Section 4 of the Constitution dictates that states determine the “Time, Places and Manner” for federal elections, and while Congress has the ability to “make or alter” such rules, it has largely left the nuts and bolts of election administration to the states. This is by design: As Hamilton wrote at the time of the founding, “the regulation of elections for the federal government” falls “in the first instance to the local administrations” which, he predicted, “may be both more convenient and more satisfactory.”

Even though the Constitution vests states—not the president—with the responsibility of election administration, federal officials have sought to extend federal control over the machinery of democracy. The administration has issued an expansive executive order targeting state voting procedures; reportedly explored ways to prosecute local election officials; and even proclaimed—wrongly—that states are the “agents” of the federal government when it comes to voting.

Since the spring of 2025, the U.S. Department of Justice has also demanded access to at least 40 states’ complete voter registration lists—and sued more than half that number—under rationales that fail to justify a need for complete, unredacted voter rolls. In the wake of 2020, when President Trump and numerous elected officials falsely claimed that widespread voter fraud tainted the results, some have suggested that DOJ’s demands are part of a larger federal effort to sow mistrust about the 2026 and 2028 elections.

It is therefore critical for state lawmakers and officials to withstand federal pressure and insist on lawfully fulfilling their constitutionally assigned role of ensuring free and fair elections.

States are already pushing back on DOJ’s demands for comprehensive voting data, including by invoking state laws that safeguard the confidentiality of voters’ private information. And while we don’t know exactly what form federal overreach might take as we near election day, states can act now to prepare for future federal interference. For example, President Trump has speculated that he might try to deploy federal forces to polling places—something prohibited by state and federal law. States can plan now for how they might respond—and should communicate those plans, in detail, to the communities targeted by intimidation efforts.

As the midterm and presidential elections draw closer, federal pressure is likely to increase; absent valid congressional legislation fundamentally changing the balance between state and federal power, states retain the constitutional authority—and obligation—to ensure that our elections remain free and fair.

Providing meaningful remedies for violations of constitutional rights

In communities across the United States, residents have recorded videos and images of federal officers aggressively using force against civilians, breaking windows and damaging property, or seizing individuals who claim to be U.S. citizens or lawful residents. At least upon first impression, many of these acts raise grave constitutional concerns.

It may surprise some to learn that today there is often no viable federal mechanism to recover damages from federal officers who violate constitutional rights. While there is a path to sue state and local officials for identical conduct—the landmark federal statute 42 U.S.C. § 1983—that law does not apply to federal officials.

Until recently, individuals could have sued federal actors under Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, a Supreme Court case that authorized damages suits when federal officials commit constitutional violations. But today the Supreme Court has made that court-created remedy, in the words of one scholar, “essentially nonexistent.” And while the Federal Torts Claims Act offers some recourse, it comes with significant hurdles and limitations that may make recovery difficult or even impossible in many cases. The result is that many victims of unconstitutional federal action lack a meaningful path to compensation.

This is where states can step in. As the State Democracy Research Initiative details in a recent publication, the possible solution of state-created damages remedies for federal constitutional violations is gaining traction. Often dubbed “Converse-1983,” the basic idea is simple: States can enact (or amend existing) civil rights statutes to allow damages suits against any person—including a federal officer—who violates federal constitutional rights. While there are some unanswered questions and possible hurdles, the historical pedigree and legal footing for such state-created remedies is perhaps stronger than some skeptics might assume: As we argued on behalf of a group of scholars in the Ninth Circuit, state-level causes of action historically were the primary way for individuals to recover for injuries caused by federal actors.

Today, several states—including California, Maine, Massachusetts, and New Jersey—already have such laws on the books. Illinois just passed a version, and New York could soon follow. Lawmakers in other states can do the same, ensuring that residents victimized by unconstitutional federal action have meaningful redress.

Holding federal actors accountable through criminal law

States also retain another familiar, and powerful, tool for checking federal abuses: criminal prosecution.

As my colleague Bryna Godar has explained, when federal officers exceed their federal legal authority or operate in an unreasonable manner, they are not shielded by federal immunity and can therefore be subject to state criminal prosecutions. In fact, such prosecutions have a long history in the United States, and we may see more soon: Multiple state and local elected officials have recently threatened criminal enforcement against federal actors who violate residents’ fundamental freedoms.

To be sure, federal officials have recently claimed sweeping immunity for any on-the-job actions. The Department of Justice’s Todd Blanche warned that the U.S. Constitution’s Supremacy Clause “precludes a federal officer from being held on a state criminal charge where the alleged crime arose during the performance of his federal duties.”

Meanwhile, presidential advisor Stephen Miller addressed ICE officers on TV: “You have federal immunity in the conduct of your duties,” and “anybody who lays a hand on you or tries to stop you or tries to obstruct you is committing a felony.”

But blanket immunity from state prosecutions is not the law. Rather, in deciding whether immunity applies, courts conduct a case-by-case inquiry that considers both the scope of the federal officer’s authorized duties and whether the officer’s actions were necessary and proper.

While this immunity inquiry will sometimes come out in the officer’s favor, there are numerous examples of state prosecutions of federal officials that have moved forward. As Godar notes, these include:

a manslaughter charge against a postal worker who hit and killed someone while delivering mail, murder charges against military members who shot and killed a man they believed was stealing copper fixtures, and murder charges against federal officers who killed a passenger when shooting their guns at a departing car they alleged was illegally transporting whiskey.

States have also initiated prosecutions against federal officers who use excessive force.

Where federal actors violate the constitution or act outside the bounds of their lawful duties—as Minnesota argued in the aftermath of ICE’s deadly immigration enforcement in Minneapolis—state criminal prosecution is potentially an important and effective tool for seeking accountability. State officials and offices with criminal jurisdiction should explore it.

Nurturing the seeds of genuine, pluralistic democracy

Finally, there is another foundational way that states can support democracy in the face of rising threats and dissatisfaction: by embodying a genuinely democratic alternative.

It is no secret that our national democracy faces significant, possibly intractable, challenges. Recent years have witnessed assaults on voting and core democratic rights; distortions of representative institutions through practices like extreme gerrymandering; and attempts to seize or consolidate power during moments of political transition. The U.S. Supreme Court appears skeptical of, if not outright hostile to, the inclusionary project of multiracial democracy embodied by the Voting Rights Act. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many report deep pessimism about the state of American democracy.

At least for now, top-down reforms appear unlikely. Troublingly, the federal Constitution itself creates headwinds to national-level majority rule through the structure of the Senate, Electoral College, and federal court system, as well as the difficulty of constitutional amendment. Some have speculated that the undemocratic nature of our national political structures has contributed to—if not directly caused—the rise of illiberalism here at home.

For all of these reasons, it has rarely been more important to envision alternative, generative forms of more genuine American democracy. Thankfully, we need not look far for models. As Miriam Seifter and Jessica Bulman-Pozen have explained, state constitutions embody a commitment to democracy that surpasses our national document. In text, structure, and history, state constitutions privilege popular sovereignty, majority rule, and political equality: a constellation the authors refer to as “the democracy principle.”

These commitments mean states are well-positioned to continue—even deepen—their tradition of experimenting with novel democratic reforms. Through ranked-choice voting, truly nonpartisan districting commissions, public financing of elections, and beyond, states have the chance to offer new solutions to old democratic problems.

Local reforms can also impact our national imagination. In their embrace of positive rights and affirmative visions of accountable institutions governing in the genuine public interest, state constitutions offer fundamentally different ways of thinking about the relationship between American communities and the officials who act in their name. And, by providing avenues for popular majorities to rule in ways that the federal Constitution thwarts, states also offer “democratic opportunities” that may even forestall further democratic decline at the national level.

At a time when many are desperate for an alternative vision of our political structures, states can already help us imagine what a more robust democratic future might look like.

Dual sovereignty

Many of us came of age in a legal culture that saw the federal government as the primary enforcer of federal constitutional rights. But under our constitutional system, the federal government does not have a monopoly on the U.S. Constitution.

Instead, our federalist structure of dual sovereignty exists precisely because there is always a possibility that a government may fail to self-correct on the road to tyranny.

When states use their lawful powers to counter federal overreach, they aren’t subverting our constitutional system or contributing to lawless obstructionism. They’re operating exactly as designed.

About The Author

Harrison Stark is senior counsel, director of special projects at the State Democracy Research Initiative at the University of Wisconsin Law School, where he focuses on civil rights and remedies, state and federal relations, and democratic rights.