Leveraging State Balance Sheets

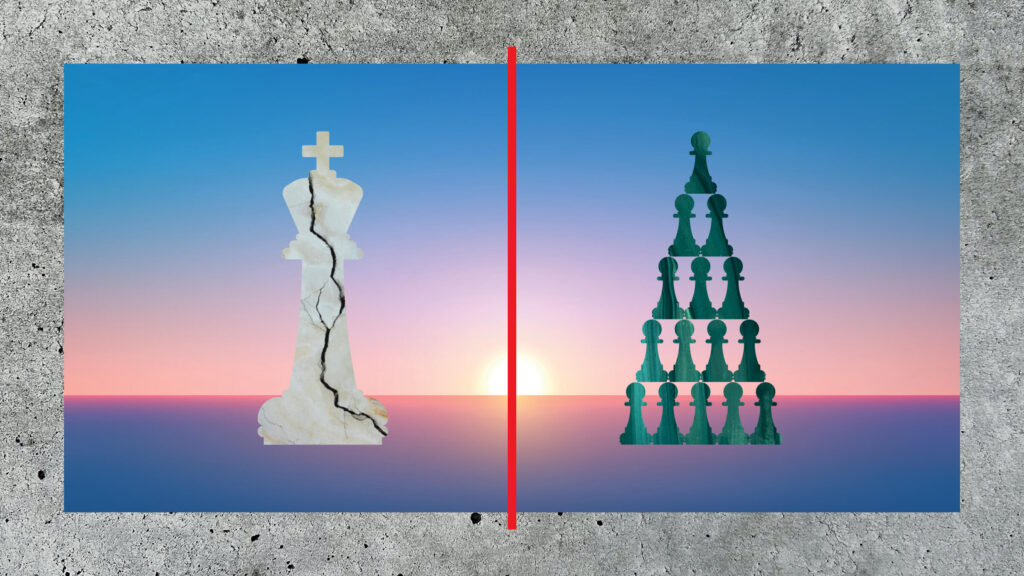

In the age of federal downsizing

- By Eric A. Scorsone

Since early 2025, federal policy has sought to downsize the overall federal workforce, cutting federal programs and significantly reducing federal discretionary spending in the process. Much of that spending comes in the form of transfers to state governments, which in fiscal year 2024 amounted to $1.1 trillion, accounting, on average, for more than 35 percent of state budgets.

These changes pose a serious threat to state and local governments’ fiscal health and key programs. In this time of uncertainty, states must begin to consider new ideas and strategies.

For 25 years, I have served in academic and government positions with a focus on state and local government finance. In the 2010’s I served as deputy state treasurer in the Michigan Department of Treasury.

During that time, I monitored the fiscal health of Michigan’s municipalities and managed debt. As the state confronted a looming crisis of underfunded pensions and spiraling retiree healthcare costs, we implemented new tools for the treasury to identify distress before it reached emergency levels. In the aftermath of Detroit’s bankruptcy, as we worked on the city’s long-term budgeting, I realized that even in the midst of financial crises, states have tools at their disposal to maintain stability.

Even so, one shouldn’t underestimate the risks federal cuts pose to states. For example, nearly two-thirds of federal transfers to states fund the joint Medicaid program. House Resolution 1, passed in July 2025, is projected to cut Medicaid spending by more than 10 percent annually over the next 10 years. This cut, plus cuts to many other grant programs—from justice and public safety to environment, energy, public health, and housing—are causing angst among state elected officials and forcing them to rethink service provision, tax policy, and regulatory actions.

In such a moment, state governments must consider all of the potential tools and strategies available to bolster their own local economies. State governments will need to use their sovereign authority and state-held assets—in the form of liquid and capital assets and state wealth funds—to reprioritize funding and redirect resources. As a complement or alternative to tax increases, which will be challenging in the current climate, states can access, invest, and manage funds to generate new nontax revenues that can help pay for key public service priorities.

State treasurers and comptrollers have already started using such innovations to leverage dollars. However, these are generally limited and are often done through federal and state exemptions, using money other than the state’s, such as college savings plans. New approaches to leveraging state balance sheets will call for a much more aggressive set of policies and a shift away from traditional money management.

States have the capacity to use their financial and capital assets more strategically and must use the tools at their disposal creatively in an era of federal downsizing.

State balance sheets

State governments hold liquid assets and capital assets, both of which can be leveraged to ensure priorities are met in the face of federal downsizing.

Liquid assets include cash and various forms of financial investments. Capital assets include buildings, roads, bridges, software subscriptions, leases, vehicles, land, buildings, and even cultural assets such as art collections. Taken in sum, U.S. state and local governments hold over $4 trillion in total assets, split between $2.2 trillion in liquid and $1.6 trillion in capital assets.

There are a variety of legal and political restrictions on some of these asset classes, making it difficult to redirect the funds; that said, in this new era of federal downsizing, state governments have to push and expand the policy boundary and seek legal recourse to ensure they can fund key policy priorities.

Cash and short-term investments. Historically, by law, cash and short-term investments are held in stable options with relatively low yield. These would typically be U.S. Treasury securities, U.S. agency securities and money market funds, for example. State treasurers and comptrollers are generally the officials charged by the state legislatures and state constitutions to manage these funds and pay the state’s bills.

Given states’ total liquid and near-liquid assets, the use of 10% of these funds could generate over $200 billion in available resources. These excess funds could be placed in a social fund where the investments would have to be justified based on a social cost-benefit analysis. Private philanthropy dollars could be paired with state investments to increase their impact in strategic areas, maximizing the benefits. By taking this approach, the state and municipalities are able to utilize existing investments to advance a public priority while also generating positive returns.

While states need to maintain adequate reserves in the case of an economic downturn or other emergency, there’s also a risk associated with doing nothing with those funds in the face of federal downsizing. State officials are guided by state laws in assessing what they can and cannot do with these funds. While the primary objective for state treasurers and comptrollers is to always ensure adequate cash flow to pay bills as they come due, states often hold cash far in excess of what they need in the short or even medium term; this money could be leveraged to generate returns to pay for other priorities.

Pension funds. Pension assets are another potential source of revenue. State governments collectively hold nearly $6 trillion in pension assets as cash, short-term financial investments, and long-term investments (depending on their specific portfolio). Although these assets must earn a financial yield to ensure payments are available to retirees, they can also be deployed to fund other state priorities, including economically targeted investments (ETIs). As the legal scholar Paul Rose has argued, viewing the fiduciary duty of public pension funds as solely supporting individual beneficiaries is misplaced; instead, a broader fiduciary standard should govern investments. If such funds were unlocked, they could provide a significant new source of revenue to states.

Capital assets—land and more. State governments hold over $1.6 trillion in capital assets; these can in part be repurposed to meet policy priorities or to yield a higher return to help increase state funding. Such ideas have been implemented in Asia and Europe, where publicly owned land is repurposed for commercial use and generates financial returns while still being publicly owned. For example, Copenhagen used a publicly owned but privately run waterfront company to engage in large-scale redevelopment and provide for a new citywide transit system without imposing new taxes. The improved commercial value of the region generates financial yields that can be used to invest in city priorities. The public/private company benefits from access to low-cost capital, due to its government relationship; at the same time, it stays focused on efficient, long-term management.

State wealth funds. Another tool is the widespread adoption of state wealth funds (SWF), also known as public wealth funds. These funds are similar to sovereign wealth funds; they invest in financial and physical capital and generate yields that can be used to fund government priorities. Some states have already created these funds, such as the Alaska Permanent Fund, the Texas Permanent School and University Fund, and the New Mexico State Investment Council Permanent Funds. These are almost all based on revenue generated by natural commodities, such as petroleum, and were created with the idea that revenue from nonrenewable resources should be banked and invested for future generations.

SWFs could be generated from other fees as well, including from toll roads and bridges, buildings and museums, art collections, natural resources, and minerals. The key here is that the private sector can be brought in to manage state assets, earning greater yield, while still maintaining public ownership and oversight. The state will have to give up some of the newfound yield to pay for the public/private partnerships. Assets generated from these sources could be placed in a SWF and benefit from financial expertise and large-scale efficiencies that are not possible for individually managed funds.

In the United Kingdom, the sovereign public sector property fund includes publicly owned real-estate assets managed by private-sector experts. The wedding of public ownership and private expertise has proved to be a powerful combination. The fund generates stable long-term returns, which help fund key state priorities such as housing, community neighborhood projects, transportation projects, and other priorities. Sweden, Denmark, Singapore, and Hong Kong have also successfully used the public wealth fund model.

The operation of any public/private partnership rightly demands proper oversight and transparency to allay potential public concerns. Well-designed oversight boards that incorporate outside neutral experts should be an essential element of any state wealth fund.

State emergency relief. If the Trump administration continues to dismantle the Federal Emergency Management Association, states will also need to begin building a resiliency fund. States could invest excess cash or appropriate new monies into the fund, which could also be fed by private philanthropy. When certain emergency conditions are met, as objectively determined by a third party, the fund would immediately begin to pay out. This would avoid the problem of slower response times from the presidential administration and congress. The fund would not eliminate the need for federal monies in the event of large and widespread emergencies.

By themselves, states can set up individual funds, and many have already done so. A more radical solution would be for states to work together to create emergency relief funds through multistate compacts. One potential hurdle is that interstate compacts typically must be approved by Congress, but states have found ways to work around this proviso (the Advanced Practice Registered Nurses Compact, for example, allows nurses to receive multistate licenses, but did not require congressional approval).

The risk of inaction

In an age of federal downsizing, state governments must step up to act on policy priorities, and treasurers must lean into a more aggressive set of tactics.

State governments are already acting in the public interest to harness individual savings and excess cash to advance policy interests through instruments like 529s and baby bonds. State treasurers and comptrollers have generally proved themselves capable stewards of these funds and could extend these practices to other investments. In partnership with private-sector financial institutions, states can leverage public and private dollars to extend social support policies that the federal government is unable or unwilling to continue.

Some will argue that states have a fiduciary responsibility to manage their excess cash in prescribed ways. Doing nothing, however, may create far greater risk than expanding the boundaries for using state government’s held funds would.

About The Author

Eric Scorsone is an expert in public finance who has worked in government in Colorado and Michigan, including serving as Michigan deputy state treasurer and in academic outreach roles working with state and local government to build financial capacity and analysis. He has published widely on state and local government finance, and is the co-editor of the Handbook of Local Government Fiscal Health.