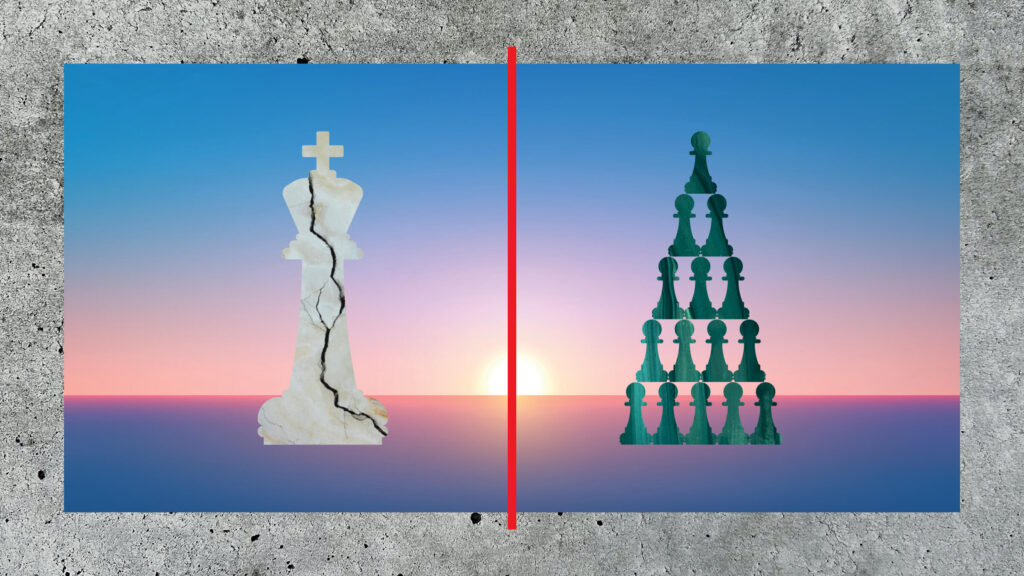

Liberalism and Patriotism

For decades, liberals have conceded “love of country” to conservatives. It’s time to align their values with a renewed sense of national pride and unity.

- By David Greenberg

It is hard to convince people to vote for you when they believe you don’t love your country.

Fair or not, the perception that liberals are insufficiently patriotic is damaging their standing today. “I really believe they hate our country,” President Trump said, referring to Democrats, in his Fourth of July speech last year. The criticism was more than just another eruption of Trump’s usual nastiness. His disparagement expressed a sentiment shared by the MAGA base—and, alas, many others. A 2025 YouGov poll found that only 21% of Americans consider Democrats “very patriotic,” and 25% judged them “not patriotic at all.”

A significant number of Democrats don’t even contest the claim. According to the Republican polling firm National Research Inc., only 50% of Democrats today label themselves as patriotic, compared to 91% of Republicans who self-describe that way. These figures mark the nadir of a roughly 10-year-long slide.

Liberals and progressives would find it easier to rebut aspersions on their patriotism if the problem were purely rhetorical. But too often they equip their opponents with ammunition. Well-to-do professionals talk about fleeing to Canada or obtaining citizenship in Europe as if America today resembled Weimar Germany. One CNN report about fairweather patriots profiled a screenwriter/novelist bound for Italy (where the governing party was not long ago decried as fascist) and a pair of teachers from the liberal haven of Asheville, North Carolina, who bolted for the freedom-loving bastion of Morocco.

Privately, some politicians acknowledge the problem, and a few reform-minded leaders have done so publicly. In a much-touted speech last spring calling out wishy-washiness on the left, Michigan senator Elissa Slotkin urged liberals to “fucking retake the flag” with unfeigned displays of national pride. John Fetterman of Pennsylvania insisted, “I’m unapologetically grateful for our nation and the American way of life—today, and always.” But these scattered declarations haven’t been followed by any wholesale shift in rhetoric, attitudes, and policy positions.

Poll numbers showing muted national pride among liberals no doubt reflect legitimate concern, despair, or anger about the right-wing dominance of the federal government and the nation’s current leadership and course. Still, it should be possible to divorce one’s feelings about this particular moment from a fundamental belief in America as a nation of noble values and great achievements.

The drift away from putting country first

The reluctance to identify proudly with America has been building for years. As Samuel Huntington diagnosed in his 2004 treatise about American identity, Who Are We?, written as the Democratic party was shedding its Clinton-era working-class appeal, the attachment liberals once felt to the country as a whole was being replaced with loyalties to “sub-national” and “supra-national” groups.

By sub-national, Huntington meant demographic clusters that constitute contemporary identity politics: groups united by race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and so on. Supra-national refers to the affiliations of global elites: business leaders relocating company headquarters or factories abroad, or cosmopolitan intellectuals who consider themselves citizens of the world.

There were several misguided aspects of Who Are We?, which flirted with a revanchist, exclusionary vision of national identity by arguing for a reassertion of the country’s original Anglo-Protestant heritage as its enduring essence. But for all his proto-Trumpian stylings, Huntington presciently identified an emergent problem that, a decade later, fueled grievances that right-wing populists seized upon.

A melting pot through assimilation

Most damaging of all, the waning national pride on the left is not simply atmospheric; it’s manifesting in policy. To address the patriotism gap, liberals will need to better articulate their love of country. But, as importantly, they can also demonstrate their love of country by seeking to improve people’s lives at the state and local level and pivoting, even subtly, on specific policy issues where they’re vulnerable.

There are lots of positions that have made the public doubtful about the left’s love of country: the instinctive aversion to even justified uses of military force abroad; failing to frame their energy policy in terms of what’s good for Americans. But probably none has hurt them more than immigration. The left lost the public’s trust on immigration in part because leaders dodged the fact that entering the country illegally is in fact illegal and should be curtailed. Few party spokespeople seemed ready to argue that upholding the rule of law is compatible with welcoming and even celebrating legal immigration, support of which has always had a patriotic (though perhaps not nationalistic) ring to it. After all, it has been America’s greatness—its freedoms, opportunity, cultural richness, and pluralism—that has lured people from all over the world. No gathering exudes a purer love of the United States than a roomful of newly naturalized citizens. No nation has been adopted by as many foreigners as ours.

Contrary to the recent nativistic rhetoric of MAGA leaders like Vice President JD Vance, America has never particularly prized a conception of citizenship rooted in blood and soil. As Hector St. John de Crevecoeur wrote 250 years ago, Americans from the beginning understood themselves as a “mixture” of peoples from diverse points of origin, “individuals of all nations … melted into a new race of men,” united not by a single ethnic lineage but by values and habits.

Immigration supporters have had trouble capitalizing on this history because, in addition to minimizing concerns about border and visa violations, the left has dropped a crucial word from its vocabulary—assimilation.

For generations, assimilation was a magic thread stitching together our multicultural tapestry. No matter where they hailed from, immigrants embraced American culture and identity—and in turn influenced it. Assimilation was never a one-way arrow; it never required the complete surrender of ethnic heritage. But somewhere along the line, many on the left came to conceive of assimilation as coercive, a cultural border control that forced newcomers to relinquish old-country traditions. The idea of encouraging all citizens to partake in common values became coded as oppressive and culturally imperialistic. Reaffirming that immigrants can be proud Americans while remaining comfortable in their ethnic identities would go a long way toward forging a patriotic rhetoric and policy around one of our most contentious issues.

The history wars

The patriotism gap can also be seen in fights over how American history is represented—in textbooks, classrooms, museums, the naming of institutions, and other forms of commemoration. The persistent sense that liberals and progressives, holding power in academia, Hollywood, the media, and other influential cultural institutions, have abandoned a shared understanding of American history in favor of an unremittingly negative one has tainted much of the public’s perception of the left.

The result has been an ugly backlash. Starting with his first term and accelerating in his second, Trump has sought to impose a crude, triumphalist account of the American story to the point of interfering with ostensibly nonpartisan institutions such as the National Archives, the Smithsonian Institution, and the National Park Service. More than politicizing formerly nonideological agencies, Trump and the right are enshrining a tendentious, distorted version of history that omits context, whitewashes shameful moments, and in crucial ways misrepresents the past.

These efforts have been widely denounced. But the right’s revisionism would not have resonated with the public in the first place if it hadn’t contained a grain of truth. Since the 1960s, historical scholarship and other public accounts of our past have—admirably—been expanded and revised to pay more attention to the experiences of Blacks, Latinos, and other minorities, to the role of ordinary citizens as well as heroic figures, and to shameful episodes and features in America’s development that dull some of the luster of older, more celebratory narratives. And although many, even most, historians and educators have tried responsibly to impart this newly complex understanding of the past to students and the public, it’s also the case that the far left has gained an outsized voice in promoting its own account of history: a mirror image of the right’s chauvinism that sees America’s past as a chronicle of unremitting oppression, exclusion, and exploitation at home, and imperialism abroad.

In the past decade, such skewed and sometimes factually dubious narratives have permeated even institutions once trusted for their impartiality and moderation, from the New York Times (with its “1619 Project”) to high school curricula. In their most politicized versions, these accounts ignore how the American project has been revolutionary—for example, the radical egalitarianism of its founding ideals (no monarchy, no aristocracy), the endurance of its constitution, or even the ethnic and religious pluralism of its citizenry. Some accounts minimize the success of Americans in overcoming discriminatory and repressive practices; others fail to recognize that slavery, racism, sexism, and subjugation were never uniquely American (or European) sins in the first place. Yet many progressives have often endorsed these lopsided accounts or acquiesced uncritically in promoting them.

Debates over “The 1619 Project” or explanatory placards in museum exhibits are usually not in and of themselves voting issues. You don’t see “interpretations of American history” in the exit polls that list the issues voters prioritize on Election Day. But these issues matter nonetheless, because they tap into primordial feelings about American identity. If progressives are seen as describing the United States as mainly a malignant actor in world history and scoffing at (or simply failing to recognize) the extraordinary levels of freedom, equality, opportunity, and prosperity it has offered, many people won’t trust them to be stewards of our national story. (By the same token, when the right is seen as promoting a whitewashed or racially exclusionary account of the American past, its leaders become distrusted by many others.)

In states across the country, battles rage in school boards over high school curricula and what version of history they depict. Protesters and counterprotesters gather to take down or defend historical monuments. We see how understandings of the past have the power to mobilize people in the present.

The answer is not to ignore decades of scholarship casting a critical light on the American past; it is to incorporate that self-criticism without going full-bore Howard Zinn. It’s not that America needs a single common story, a noble lie to keep the masses at peace. Finding ways to express patriotism in the public arena doesn’t require engaging in hollow gestures of obeisance, like voting (as Congress has in the past) to keep the constitutionally suspect phrase “One nation under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance.

On the contrary, a nuanced version of history should be promoted because it’s intellectually honest. It also carries political benefits when liberals demonstrate their respect for the public’s ability to see the complexity in history. Showing an appreciation for America’s achievements, while also acknowledging the internal conflicts of the past, might also go some way toward overcoming today’s poisonous polarization.

The tranquil and steady dedication of a lifetime

Establishing patriotic bona fides is an old and familiar challenge for the left. In the 1960s, strident, extreme forms of opposition to the Vietnam War and a highly visible radical critique of America (as a fascistic state called “Amerika”) saddled liberals with a credibility gap on civic devotion that Richard Nixon exploited.

This dynamic endured for decades and has never been totally dispelled. In the 1988 presidential election, George Bush, Sr. assailed his Greek-American rival, Michael Dukakis, as un-American, belittling the governor’s alleged view of the United States as (in Bush’s words) just “another pleasant country on the U.N. roll call, somewhere between Albania and Zimbabwe.”

Four years later, Bush tried and failed to use the same playbook against Bill Clinton, accusing him of opposing the Vietnam War from “foreign soil” (Clinton was at the time a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford). Barack Obama also endured constant slurs on his national identity: Videos circulated showing him without his hand on his heart during the national anthem, and radio hosts spun conspiracy theories out of his foreign parentage and a childhood spent overseas.

Beyond the right’s political exploitation of it, one reason this liability endures is philosophical. There’s an inherent tension between devotion to country, at least as it’s naively conceived, and certain tenets of liberalism—a tension that, while hardly insoluble, resurfaces in fraught times.

Unlike liberalism, conservatism rests on principles of duty, reverence for tradition, and deference to authority, all of which make it easier for the right to embrace an uncomplicated—or even jingoistic—attachment to country. Conservatives tend to brandish their nationalism through a muscular military posture and an appeal to old-fashioned values. They favor an unhesitant participation in collective rituals like waving the flag, reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, and engaging in public prayer.

A classic statement of this conservative patriotism was Ronald Reagan’s farewell address in January 1989. Surveying his two terms, the president, long partial to chauvinistic bombast, boasted of having “rebuilt our defenses,” facing down the Soviet Union, and winning the Cold War. This led, he argued, to the “the resurgence of national pride that I called the new patriotism … one of the things I’m proudest of in the past eight years.”

Reagan cautioned that such liberal doctrines as relativism and self-criticism threatened this revived morale. Although he called for an “informed patriotism,” what he prescribed was the opposite. “Younger parents aren’t sure that an unambivalent appreciation of America is the right thing to teach modern children,” he fretted, calling for a return to a time when “we absorbed, almost in the air, a love of country and an appreciation of its institutions.”

Liberalism need not lead to moral relativism. But it does prize individualism, dissent, and the questioning of authority. Cherishing these values makes liberals inherently suspicious of calls for the unambivalent acceptance of any official position. For good reason, liberals question patriotic pageantry, enforced conformity, and hero worship. They find it hard to see mass displays of flag-waving without recalling the cynical and invidious ways in which Nixon, Reagan, the Bushes, and others have exploited the symbol.

Most liberals, of course, do love their country; it’s just that their version of patriotism is more nuanced than Reagan’s and, politically, a harder sell. The liberal understanding of patriotism calls for candidly identifying what’s wrong with America in order to improve it. It tends to regard rote collective gestures like the Pledge of Allegiance as somewhat hollow, tokenistic, and potentially coercive—antithetical to the individualism that lets free thought flourish. But liberalism still takes pride in the American traditions of democracy, liberty, and the pursuit of equality, and in American achievements in culture, science, industry, and social progress.

A liberal counterpart to Reagan’s farewell speech can be found in a 1952 speech delivered to the American Legion by Adlai Stevenson. Stevenson, who at the time was running for president as the Democratic nominee, contrasted what he considered “true patriotism” with the McCarthyite right’s “intolerance and public irresponsibility … cloaked in the shining armor of rectitude and righteousness.” He argued that “in its large and wholesome meaning,” patriotism “is not the hatred of Russia; it is the love of this republic and of the ideal of liberty of man and mind … not short, frenzied outbursts of emotion, but the tranquil and steady dedication of a lifetime.”

In its liberal conception, patriotism entails “tolerance,” “humility,” and respect for dissenting opinions, because, as Stevenson put it, “our capacity for change [and] our cultural, scientific and industrial achievements, all derive from free inquiry, from the free mind.”

Stevenson’s patriotism (and liberal variations on it) have often, though not always, proven too high-minded or subtle to be widely appreciated. But the merits are real: It allows for an honest reckoning with the country’s troubled past and current divisions, upholds the value of freedom of speech and thought, and appeals to our better angels.

And it’s not necessarily unpopular. A 2025 YouGov poll showed that twice as many Americans define patriotism as “acknowledging problems in your country and seeking solutions” (62%) than as “supporting your country unconditionally” (28%). Large majorities said it can be patriotic to engage in activities like participating in peaceful protests, criticizing the president, and criticizing aspects of the American past.

It’s fine for liberals to hoist the flag when the occasion calls for it, but flag-waving and wearing lapel pins can also come across as right-wing forms of virtue signaling, and proud Americans can legitimately stand apart from such gestures. The thing is, if you’re going to stand apart, you also need to make clear where and how you and your fellow citizens stand together.

Liberal patriotism redefined

Skillful liberal politicians have found ways to reclaim patriotism.

After the deadly 1995 bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City, Bill Clinton reached for Reaganesque (but not jingoistic) language in comforting local citizens, speaking of the victims as people you would see “at church or the PTA meetings, at the civic clubs, at the ballpark.” He rebuked the militia groups and domestic terrorists who had appropriated the “patriot” label for their violent, reactionary agenda.

“How dare you call yourselves patriots and heroes!” he said in a subsequent commencement address. “There is nothing patriotic about hating your country or pretending that you can love your country but despise your government.” Positioning himself as a voice of national unity, he framed the attack not in partisan terms but as an assault on the American community, fusing love of country with respect for democratic institutions.

Obama likewise found a patriotic register that allowed him to blunt attacks on his Americanness. Like Stevenson, he celebrated “the idea…that we can say what we think, write what we think, without hearing a sudden knock on the door…that we can participate in the political process without fear of retribution,” as he said in his 2004 convention speech.

Obama called out America’s diversity as a key to its glory. “We are a nation of strong and varied convictions and beliefs. We argue and debate our differences vigorously and often,” while maintaining that those differences existed within a context of shared underlying values. Time and again, he recounted a historical narrative that spotlighted reformers from “Seneca Falls and Selma and Stonewall,” as he once put it, who loved the United States enough to extend its blessings to ever-widening circles of Americans. He even cast his own success as a referendum on America’s admirable ability to overcome the racism that pervaded its past.

Emerging national leaders can also point to their experiences at the state level, where they have been able to display a quieter and more constructive form of patriotism—one demonstrated through governing rather than grandstanding. When governors or other state politicians talk about strengthening public education, or making housing, healthcare, and college affordable, or safeguarding civil liberties, they can do so in the language of upholding American values. Indeed, state-level governance provides tangible ways that liberals can attest persuasively to their love of country without succumbing to blustery chauvinism.

The rhetoric of patriotism is hardly unavailable to liberals and progressives. Nor are policy positions that would signal clearly to the public that they see America, in the main, not as a committer of sins but as a force for good. In contrast, failing to rediscover a proudly patriotic idiom will likely further alienate growing swaths of the electorate and relegate them to a marginal position, as occurred in the post-Vietnam years.

Ironically, today, as so many of the things that have made the United States a beloved country and beacon to the world stand imperiled—our respect for law, our success and achieving great freedom alongside equality for all, our ability to work across political differences—many liberals are being reminded of the reasons they do indeed love their country. The challenge is then to put this rekindled patriotism into practice.

About The Author

David Greenberg is distinguished professor of history at Rutgers University. He is the author or editor of several books on American history and politics. His latest book, John Lewis: A Life, was a 2025 finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Biography.