The States’ Secret Weapon: Reclaiming the Authority to Limit Corporate Power

Healing American politics is as simple as dusting off a resource hiding in plain sight in our constitutional toolbox

- By Tom Moore

American democracy has taken a beating in recent years, and it’s no longer clear that our institutions can withstand the forces pressing against them. On the question of money in politics, many Americans have come to believe there is no remedy for Citizens United other than waiting it out—waiting for a constitutional amendment or a change of heart at the Supreme Court.

Yet even in moments when national institutions feel paralyzed or overmatched, American democracy retains one of its most durable structural strengths: the capacity of states to act. Federalism was designed not only as a division of the workload but as a safeguard—a way for states to preserve democratic self-rule when the national system strains under pressure.

One way American democracy has prevailed over time is by adapting rather than merely enduring. In moments of strain, we have reached into our constitutional toolbox and dusted off long-neglected powers. The Civil Rights Movement is the clearest example. Through years of organizing, sacrifice, and sustained legal pressure, it revived the long-neglected and long-suppressed powers of the Reconstruction Amendments to dismantle Jim Crow. The authority had always been there; it took extraordinary effort during a prolonged democratic crisis to bring it back into force.

We could use some of that spirit of revival in this moment, when Americans’ confidence in their democracy has been beaten down by 16 years of Citizens United and the adverse effects of corporate and dark political money. Although there are real differences in scale between our present circumstances and the moral stakes of the Civil Rights Movement, the underlying pattern remains instructive: American democracy can regain its footing by utilizing a resource that was always there.

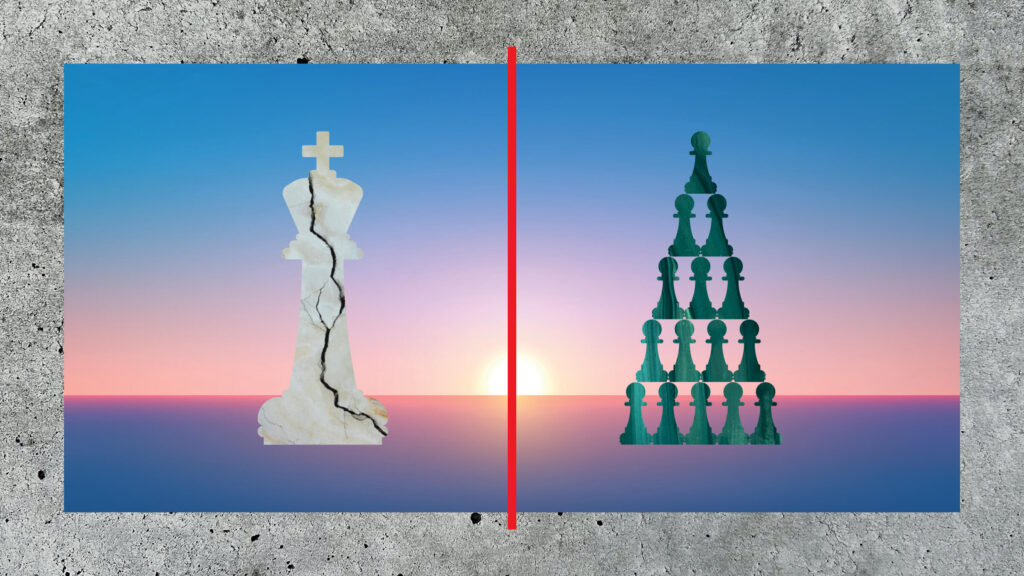

The tool coming back into view today is almost embarrassingly straightforward: the unchallenged, absolute authority of states to define their corporations. This authority can be wielded to sideline Citizens United altogether and banish corporate and dark money from every level of American politics. It’s not regulation. It’s redefinition, a return to asking and answering the fundamental question of what powers a corporation should have in the first place.

And even before any state acts, the simple gesture of pulling this tool out of the toolbox—of examining it, naming it, and swinging it around a little—has begun to give people something they haven’t felt in a long time: a sense that they still have a hand in shaping the system that governs them.

The reemergence of this dusty but still impressively powerful weapon affirms to Americans that they are not powerless in their own political system, and that the capacity to reclaim their democracy has been in their reach all along.

Countering the destructive force of Citizens United

Since Citizens United took a wrecking ball to campaign-finance law in 2010, unlimited outside spending has swamped local, state, and federal elections; distorted primaries and fueled polarization; and deepened the sense that democracy responds to wealth rather than to voters.

The numbers tell the story: Before Citizens United, outside spending in federal elections totaled $574 million in 2008. By 2012, that figure had more than doubled to about $1.3 billion, and by 2024 outside spending had ballooned to roughly $4.5 billion. Super PACs alone have poured nearly $3 billion into federal races over the past decade. Dark-money groups, whose donors are not disclosed, have grown from virtually nothing into hundreds of millions per cycle, with more than $300 million spent in 2012 alone. In the 2024 election, just 100 billionaire donors contributed roughly $2.6 billion, underscoring how concentrated political spending has become in the post-Citizens United era.

The idea for a different path through the Citizens United thicket did not spring from the Capitol or the courts or the usual channels of constitutional change. It grew out of a decision 10 years ago at the Federal Election Commission to take a hammer to Citizens United and see what, if anything, could be beaten out of it.

It was a ripe target: Citizens United is a poorly reasoned, results-oriented decision that distorted both First Amendment doctrine and corporate law; while it would not be overturned anytime soon, perhaps it could be outflanked. That line of inquiry produced two early projects: The first provided a legal foundation for foreign-influenced corporation laws; the second questioned whether corporations’ political-spending authority actually flowed through their boards.

As the study of power went back to the source, a different picture—and a third major project—emerged. What matters most, it turns out, is not what Citizens United said about speech, but what it assumed about the powers the states had given their corporations.

States create corporations. Every power corporations possess begins with a state’s choice to grant it through its corporation laws. But a century ago, when competing against other states for corporate-charter revenues, the states gave away the store, granting every corporation the power to do anything legal—the same powers as a natural person. Citizens United (the decision) treated Virginia’s broad statutory grant of “the powers of a natural person” to Citizens United (the nonprofit corporation), including the power to spend in elections. Because it had the power, the Court reasoned, it had the right.

The decision was instantly applied to nonprofit and for-profit corporations in every state, suddenly allowing them to spend independently in elections at every level.

And that, thought many people, was that. The Supreme Court went on to knock down state laws regulating corporate political expenditures; it killed Montana’s century-old Corrupt Practices Act with a one-page decision.

But in all this litigation, the Court never said any state had to grant political-spending power to corporations in the first place. That is the crucial point: The way to beat Citizens United does not require attacking the First Amendment (or even attacking Citizens United); it turns instead on harnessing the authority states have to confer powers on the artificial persons they create, because states never relinquished their ability to define and redefine (or even eliminate) the corporations that operate within their borders. The Supreme Court has long treated that authority as virtually absolute.

The authority to define—and redefine—corporations

Though states have always held the authority to define their corporations, over time that authority fell into disuse. People forgot they had it. For more than a century, that authority was obscured by the smooth, uniform surface of modern corporate law. As states steadily broadened corporate-purpose clauses, they functioned almost identically, and corporations came to operate across the national economy with little regard for the specifics of any one state’s statutory choices.

The power to revise and revoke is still there, fully intact and available, and all a state needs to do is the legislative equivalent of tapping its heels to invoke it.

Here’s one way to think about it: If you live in a house with hardwood floors and cover up every inch with wall-to-wall carpeting for long enough, you eventually forget what lies beneath. You know the floors are there, but there is no good reason to talk about them, because everything important happens on the surface.

This is what happened with corporate powers. The broad-purpose clauses adopted during the interstate chartering race at the beginning of the 20th century created a kind of legal carpet—a uniform, undifferentiated layer that made it easy to forget that underneath it all are 50 separate bodies of state law, each one creating its own corporations and extending reciprocity to every other state’s corporations.

In the earliest years of the Republic, those 50 bodies of law mattered. Corporations were not created to be general-purpose economic actors. They existed because states saw specific public needs—bridges, canals, banks, ferries—and created narrow vehicles to meet them. Charters were tailored instruments: limited in time, limited in scope, and justified only when the project served the community. A corporation existed because the people, through their legislature, decided it should, and it possessed only the tools necessary to complete its assigned task. Its powers were limited, its lifespans short, and its activities closely tied to the public interest.

This process was terribly time-consuming—each special charter was a separate private bill passed by the legislature—and terribly corrupt. States shifted in the mid-19th century to general charters that could simply be applied for and paid for. This was not done to liberate corporations but to eliminate the inefficiency and favoritism of special-charter politics. Industrialization changed the stakes. As railroads and national commerce expanded, states discovered they could attract incorporations—and lucrative fees—by offering broader powers. New Jersey liberalized its statutes first; Delaware soon followed; by the early 20th century, states were competing to grant the most permissive charters. Within a generation, “any lawful purpose” clauses had become the national norm, and the dominance of national corporations carpeted over the states’ underlying power.

Frankenstein’s monster vs. the townspeople

By the early 20th century, this shift carried real political consequences. Corporations were no longer small, time-limited enterprises tied to local purposes; they had become national institutions with wealth, scale, and permanence whose power no individual citizen could match.

Justice Louis Brandeis saw the danger early. In Liggett v. Lee (1933), he warned that states, by steadily enlarging corporate powers, had enabled a system in which “200 non-banking corporations … control directly about one-fourth of all our national wealth,” and are run by a few hundred “persons,” a structure he described as “the negation of industrial democracy.” “Such,” he concluded, “is the Frankenstein monster which States have created by their corporation laws.” The larger and more interconnected corporations became, the more easily they could concentrate economic power, influence legislation, and shape public life.

In some areas, the imbalance is obvious. Under California’s Proposition 13, for example, property taxes reset when ownership changes hands—something that happens to people but not to corporations, whose perpetual existence allows them to retain artificially low assessments for decades.

The same dynamic plays out in politics. Corporations can route money through layers of entities, funding ballot measures, issue campaigns, and independent expenditures in ways that ordinary citizens cannot. The cumulative effect is a political environment shaped by institutions whose economic power gives them a reach far beyond the scale of any individual citizen’s voice.

Against that backdrop, the rediscovery of state authority over corporate powers lands with unusual force. It offers a democratic remedy that does not depend on Congress, the federal courts, or the shifting preferences of national actors, but on something far closer to home: the ability of states to decide how to empower the corporations they create. The same authority that once constrained corporate size, scope, and influence has not vanished; it has merely gone unused. And unlike so many proposed ends to the Citizens United era, this one does not require a constitutional amendment or a national consensus. It requires only that a state remember its role in shaping the artificial “persons” that operate within its borders—and choose to exercise that role again.

That rediscovery also has the rare quality of helping both political parties at once. Corporate and dark-money networks aggressively distort both parties’ primaries. Each party has its own experience of being swamped by spending from organizations with no ties to the voters who must live with the consequences of a skewed election. In a political era defined by hyper-partisan conflict, this is a reform that does not tilt the playing field toward either side. It simply restores the basic premise that state politics should reflect the will of the people who live there, not the preferences of corporations (including those from other parts of the country) empowered to spend without limit.

Power to the people

At its core, this is a reminder about the relationship between the public and the corporate form. Corporations are not independent political actors with inherent claims on democratic space; they are artificial persons created to serve the communities in which they operate. Their powers exist to facilitate productive activity, not to overshadow the political voices of citizens.

When states revisit those powers, they are not punishing corporations but clarifying a relationship that has drifted out of balance—and revealing that the balance has always tilted more toward the public than many realized. The people, acting through their states and using authority reserved long ago by corporation-wary lawmakers, remain in charge. This reform simply reaffirms a proposition earlier generations took for granted: Corporations are built to serve people, not the other way around.

Once that relationship is made clear, the path for states becomes surprisingly straightforward. A legislature can revisit its corporate statutes, identify the broad-purpose clauses that, decades later, turned out to authorize political spending, and draw a cleaner line between the powers corporations need for ordinary business and the powers that belong only to citizens. A state need not alter tax law, rewrite campaign-finance codes, or create new enforcement agencies. It need only specify that the artificial persons it creates are authorized to engage in commerce, not politics.

And because states also choose whether and on what terms to recognize artificial persons chartered elsewhere (“foreign corporations”), the effect is not confined to corporations within state lines. When a state sets the list of powers its artificial persons possess, that is also the list of powers possessed by the out-of-state corporations doing business within its borders. The result is a uniform rule: No corporation, whether domestic or foreign, may claim a political-spending power the state has chosen not to grant.

A state that passes this reform disempowers every type of artificial person, no matter where chartered, from spending on ballot issues within the state and on the local, state, and federal elections within that state. Because of the Supremacy Clause, this almost never happens—that a state-law change can affect political behavior at the federal level—but, as we know, artificial persons get every one of their powers from the state, including the power to spend in federal elections.

This is not a complicated reform, and it lies entirely within the authority states have exercised since the beginning of the Republic.

When a state chooses to draw that line, the effects reach far beyond matters of campaign finance. The act itself restores a measure of democratic agency to the people who live there by reminding them that the institutions shaping their political lives are not forces of nature but creations of their own laws.

In an era when many Americans feel voiceless in their own democracy, the rediscovery of this long-neglected power offers a quiet but genuine reassurance: We can roll up our sleeves, pick up the tools, and repair our democracy. State by state, we can peel back the carpet and see the hardwood floors again—and see that the foundations of democratic self-government are still sturdy, still available, and still ours.

About The Author

Tom Moore is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. Previously, he served as chief of staff to former FEC Chair Ellen L. Weintraub, was elected to the Rockville, Md., city council, and wrote and edited for Congressional Quarterly and CNN.