Why We Need a New Working-Class Movement, Not Just Another Political Campaign

Not Just Another Political Campaign

- By Matt Morrison

During the many hours I spent talking to swing voters during the 2024 election, one interaction has come to illustrate the dynamic that I believe ultimately sunk Democrats. It also holds the key to mounting a strategic resistance to Trump at this moment.

During the many hours I spent talking to swing voters during the 2024 election, one interaction has come to illustrate the dynamic that I believe ultimately sunk Democrats. It also holds the key to mounting a strategic resistance to Trump at this moment.

I was speaking with a Black woman in her mid-30s in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. Her hands were full, literally, with a 10-month-old infant while a shirtless, energetic 3-year-old darted around her legs, football in hand. She had the harried, exhausted look I have seen many times on the faces of parents of young children—she needed help.

As I was there to make a case for Kamala Harris and the Democratic ticket, I talked to her about the expanded child tax credit that Biden had created for parents like her, and about the childcare policies and subsidies Harris was proposing. I contrasted that with the lack of any meaningful support for parents being offered by the Trump campaign.

It wasn’t just that this young mother had never heard about any of these policies (by that point in the campaign, this was sadly unsurprising). It was that even after I told her about them, it seemed to have very little impact on her vote. She just shook her head and said she would vote for Harris, with a sad lack of enthusiasm or certainty. Young, Black, female, and living in a city, she was exactly the kind of voter that pundits assumed were in the bag for Kamala Harris. But she wasn’t. In her mind, there was no reason to believe that Democrats, or anyone else, had her back.

The problem was not just one of communication or messaging. It was about a fundamental lack of trust that was built on a disconnect between her own lived experiences and the kinds of policies and programs that national politics presents as “solutions.” Those policies, even if they were aimed at solving her problems, were born from a different universe of experiences, and she knew it.

The data shows that many of the Democratic messages did get through. But it’s also clear that the other side of the debate was not hampered by the same disconnects that our side was. We may have built a good campaign. But the other side had built a movement.

Nothing we could have done would have matched the intensity and belief of Trump’s core voters. But even more dangerously, in the long run, Trump’s campaign captured many less-political voters, because these voters start off with fundamentally different foundational narratives about the political system. The starting point for political persuasion has not just moved to the right; for many voters, it has jumped off the right-vs.-left axis entirely. It has instead shifted to a debate that is more dangerous for those of us who hope to use the power of government to strengthen equality and justice. It’s now a debate over whether government is relevant at all.

That’s the debate I wound up in with the woman from Pittsburgh. It’s the debate we lost last fall. But there is new data emerging that Trump’s particularly virulent brand of chaos may provide the foundation we need to turn the corner on this argument—especially in the places where it matters most to electoral fortunes.

Where the vote moved

Our analysis of the 2024 election is built on the three million conversations (meaning both speaking and listening) we had with voters at their doorsteps in the swing states of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. It’s an operation that took roughly a million person-hours of work and Lord knows how many miles tirelessly walked by our 5,600 canvassers. That’s the core of what we do at Working America, which is the community-organizing affiliate of the AFL-CIO, the nation’s largest labor federation. We are fortunate to be able to conduct canvassing at such a scale, which was largely unmatched in Democratic politics, and it gives us a unique insight into what is on the minds of regular voters—even the disengaged ones who don’t answer the phone for pollsters. We also maintain a robust survey operation, tracking the responses of the same voters over years.

No election involving nearly 160 million people can be attributed to any single, simple trend. Yet the data combine to tell us that, contrary to the dominant narrative, “vote switching”—where large swaths of voters defected from Democrats to back Trump—was not the largest factor in the election’s outcome.

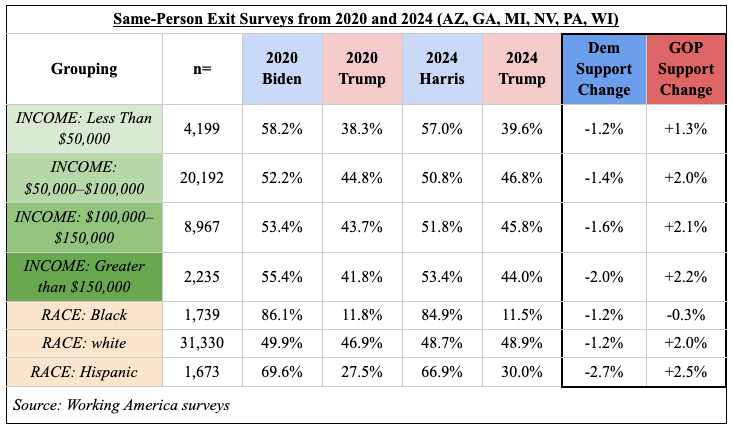

That is not to say vote switching was nonexistent. According to our tracking poll of the

same 36,000 battleground-state voters from 2020 to 2024, Democrats didn’t lose much of their base after 2020, even after Biden’s much-discussed debate performance. Of those who were lost, white, Hispanic, and high-income voters were most likely to switch to Trump or a third-party candidate.

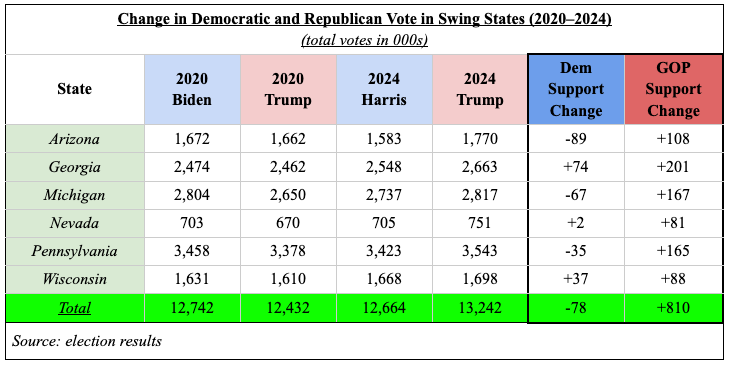

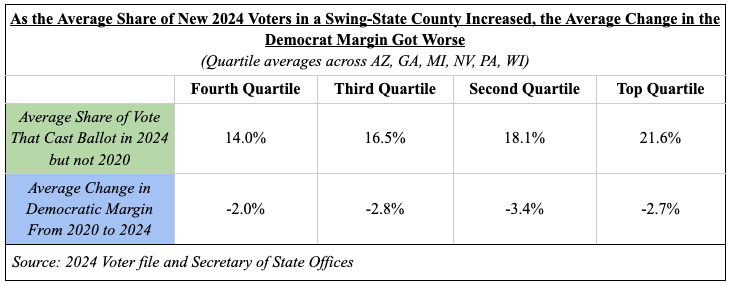

Rather, the change in the popular vote from 2020 to 2024, at least in the critical swing states, largely reflected Trump’s ability to attract new voters, as many Biden voters stayed home. While Harris was 80,000 votes behind Biden’s 2020 totals in the battleground states, Trump added 10 times that many to his total. Even if Harris had been able to win exactly the same number of voters that Biden did in 2020, Trump added enough new voters that Democrats still would have lost Georgia, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—and therefore the presidency.

While we do not know how every individual voted, one strong indicator of a voter’s preference is geography. A new voter from the middle of Philadelphia (which Democrats won by 58 points in 2024) is statistically likely to be a Democrat. A new voter from the rural Pennsylvania county of McKean (which Republicans won by 47 points) is statistically likely to be a Republican.

Across Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, we have enough data on individual voters to see that where more voters were new to the electorate in 2024, the shift in margin towards Republicans was larger.

It wasn’t just the vibes

Why didn’t new voters respond to the Democrats? We got a preview way back in February 2024 when we had a series of in-depth conversations with 11,000 voters at their doors. At the time, we sought to understand why popular polling on the economy was at such odds with the macroeconomic data that showed a strong economy. Why were “the vibes,” as many commentators took to calling them, so negative on Biden’s economy?

This was where talking to folks at the doors made a real difference—we learned that the messages of economic success coming from the then-Biden campaign were often deeply disconnected from the lived experience of those same voters he was counting on.

Despite a labor market called “sizzling” and “shockingly good,” just under half of the people we spoke with had personally experienced an increase in pay over the previous year. Meanwhile, everyone had experienced cost-of-living increases. Only white workers were more likely than not to have seen an increase in pay. Among the voters who were crucial to Biden’s 2020 coalition—people of color, women, and young people—a majority told us they had not had a raise in the last few years.

We found that a person’s direct experience with stagnant wages correlated with their view on the state of the economy. It didn’t matter what the Dow Jones was doing or how much the GDP was growing. They were seeing the price of groceries go up and their pay stay flat.

You see the results on Election Day—the biggest drop-off in voter participation from 2020 to 2024 was concentrated among voters from households earning less than $50,000 per year. The benefits of the Biden economy did not reach those voters, and they stayed home.

Confidence in delivering

Contrast this with the certainty of Trump voters that their candidate would deliver.

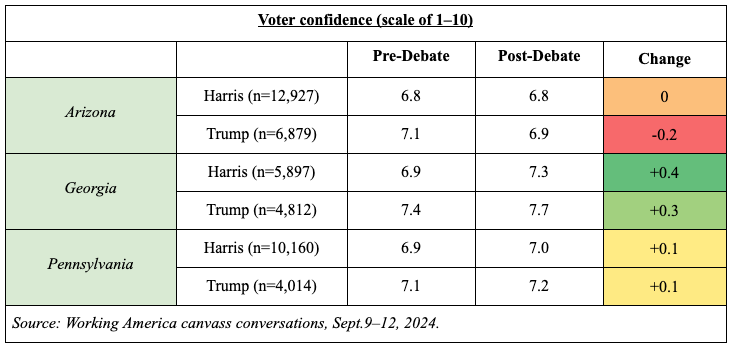

In September 2024, we asked 44,689 voters in Arizona, Georgia, and Pennsylvania to rate on a scale of 1 to 10 how confident they were that the candidate of their choice could deliver on the issue most important to them. Trump voters averaged 7.2 while Harris voters averaged 6.9. Harris’s lopsided dominance during the debate (we spoke to voters both before and after) didn’t close the gap.

There was also ample anecdotal evidence from our canvassers that Trump supporters in the swing neighborhoods that we targeted felt emboldened while Harris supporters felt nervous. Many Harris supporters were reluctant to come out from behind their doors or asked us to keep their support secret from their neighbors. Meanwhile, most of our canvassers came to expect that at least one Trump supporter would accost them or harass them on the street every day.

The worm turns

But feelings have shifted since Trump took office. Now it is Trump’s own base expressing a sense of disconnect between what’s happening in Washington and their own lives

In April 2025, we conducted a Front Porch Focus Group, holding 5,306 in-depth phone conversations and 2,756 online-survey interviews with voters in 19 of the most competitive Congressional districts and five of the most competitive 2026 U.S. Senate states. Republicans are currently holding office in 13 of those 19 competitive districts and all five of the Senate seats—they are the only targets both vulnerable to political pressure and with power in this moment to stop Trump’s legislative agenda.

Except for the hardest-core GOP voters, the strong majority were disapproving and worried about their financial standing. The committed Republican voters in these districts, a key constituency for these members of Congress, remain deeply approving of Donald Trump on everything from the economy to foreign policy, which is not surprising. But what’s interesting is where the data starts to get messy—the policies of the Trump administration are far less popular than Trump himself.

Once again, this seems to be because the arguments coming out of Washington make no sense to the lived experience of voters in these districts. In Trump’s case, both his tariff regime and his spree of government service cuts have landed badly with his most loyal voters.

“This tariff stuff is crushing me,” said a voter in North Carolina named Caleb, a loyal Republican who called himself “one of the biggest MAGA people around.” “The billionaires don’t care. They don’t need the money…. Make sure to put down that this tariff stuff is outrageous.” Right after telling us this, we asked Caleb to rate Trump’s job performance on the economy. His answer? “Strongly approve.”

That dichotomy was everywhere in these competitive districts. While 66% of these “strong Republican” voters said the economy was on the right track, only 36% of them said they felt positive (“confident” or “excited”) about their own financial future, while another 29% said they felt “hopeful.” Only 32% of strong Republicans said their own financial situation had improved since the start of the year, with the remainder saying it was worse or they were not sure.

Given the sky-high levels of confidence that Trump’s base had last fall that he would deliver for them, the fact that only one-third of them have had any positive experience in their own personal prospects should concern the Republican supporters of Trump’s agenda in Congress.

We saw a similar disconnect with the government cuts. While most Republican voters approved of Trump’s job performance on federal spending, far fewer specifically approved of the implementation of those cuts through DOGE. Many Republicans told us they were worried about the cuts and the way they were being implemented, especially the potential for cuts to Social Security or Medicare. A full 90% of these voters told us in our online survey that they thought the government should spend the same amount of money or more on these two programs.

The path forward

Trump’s chaos provides an opening—but it’s hardly a guarantee. The polls that are showing plummeting approval rates for Trump nationally are showing that Democrats are doing even worse. Right now, many of these voters trust nobody.

How to win their trust?

Part of it comes down to, as many good coaches tell their team, just “doing the work.” Continuing to have conversations with voters in these communities about what matters to them, and doing more listening than speaking, are imperatives. This is not a noble declaration for grassroots engagement, but rather an observation that the evidence is clear that maintaining communication with voters outside of elections adds a meaningful advantage in winning more votes in elections.

But simply speaking to voters without also addressing the government to the needs of people with flat wages and rising costs ensures a recurring cycle of the types of losses seen in 2024. Democrats cannot rely on Republicans being vulnerable in 2026 based solely on Trump’s declining popularity. As we can see in the data above, the coalition of voters who may oppose Republicans is far from certain. These folks are asking for answers, and the party needs to have some at the ready. Democrats did not have credibility on an emotional, gut level with the working-class voters they needed to win. And just as important, it cannot wait until 2026 to create political pressure on Republicans; their deeply harmful agenda needs to be stopped right now.

So if we know that Democrats must engage meaningfully with working-class voters and advance policies that meet their needs, and if that also seems unlikely in a GOP-dominated Washington, that leaves the state and local governments among the key actors. By proposing and enacting programs that create real change in unfair systems and provide real relief to the everyday problems faced by these voters, Democrats can demonstrate an alternative vision of what government can be.

Those of us seeking to create a working-class coalition need to keep people’s needs and concerns front and center, but we have to infuse our organizing with a level of political education and cross-racial class solidarity that our movement has often lacked. We can’t shy away from explicitly thinking and talking about class, because the billionaires certainly aren’t afraid to think that way. And a true working-class movement, independent of any political party, will be a far more effective messenger to voters than any candidate about who is and is not on the side of working people.

Building a working-class movement is key to the future success of Democratic candidates. But more important, it may be the only hope we have of countering the rise of authoritarian Trumpism in our country and preserving the multiracial democracy that guarantees rights for us all.

About The Author

Matt Morrison is the executive director of Working America, an organization for working people without a union on the job. He is a nationally recognized political practitioner, with experience working in more than 700 elections over his career.