- Cost of Living

De-Gouging the Economy

By Rohit Chopra, Former Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and former Commissioner of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission

The idea

Since the pandemic, families are angry about the increasing costs of everyday essentials and monthly bills. Given the lack of meaningful rationale for rising prices, many consumers feel gouged with few options to fight back.

Policymakers and political leaders often respond with band-aid solutions that rarely attack the root problem. For example, states pour subsidies into the private sector or provide financial support for struggling families, but these approaches typically don’t do much to address rising costs.

Of course, policies set at the federal level, like on trade and housing finance, play an enormous role in the cost-of-living crisis. However, states have powerful—and often overlooked—tools at their disposal to actually drive down the costs that families face. Importantly, the benefits come much sooner than traditional solutions that take years to implement.

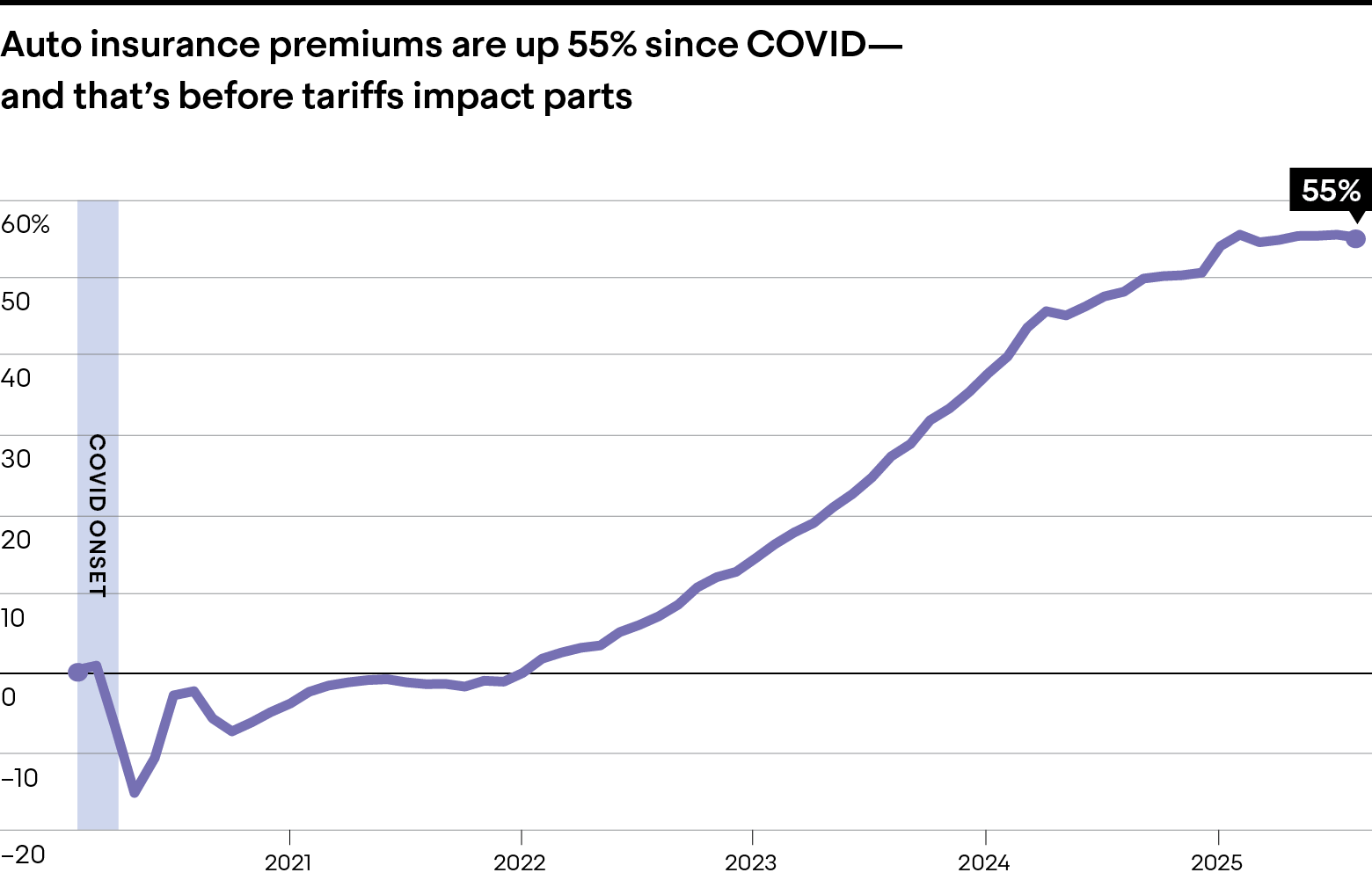

First, states can use existing laws on the books to reboot their state regulators. These regulators often have existing authorities to limit price increases, or drive price cuts on major monthly bills. For decades, states have enacted statutes that give state agencies, commissions, and other regulators the power to accept or reject pricing changes on a range of monthly bills, like auto insurance and electricity. As these costs surge, states must now scrutinize these prices for opportunities to find savings.

Second, states can charter a new competitor to foster more affordable pricing. Public competitors are state-established enterprises or procurement efforts by existing agencies that either sell directly to consumers or serve critical functions that lower costs for retailers or distributors. For many decades, public competitors have provided key infrastructure to lower prices and support competitive markets. Whether it’s the state-owned Bank of North Dakota established in 1919, or the more recent launch of California’s insulin distributor, public competitors have real power to lower costs.

Third, states can directly establish price protections. This can take the form of banning fees or even, in appropriate instances, capping prices. When done right, this can increase affordability, promote competition, and minimize shortages and disruptions. While governments have regularly pursued price floors for certain goods and services, price ceilings can also play a role to block price gouging and ripoffs. States can legislate these changes or negotiate these anti-gouging measures when providing state support to private sector businesses. Simple, well-designed price ceilings, like interest rate and fee caps, can similarly provide needed relief and reduce the need for complex and confusing regulations.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen eye-popping increases in the value of assets, especially residential real estate.1 This means that the entry cost for homeownership surged. For example, in the years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, the average age of a first-time homebuyer was 30 years old. Today it is 40.2 In almost every one of the top 50 metropolitan areas, median earners cannot afford a home.3

And it isn’t just housing. In the aftermath of COVID-19’s economic interruptions, margins (the markup that companies charge consumers above their costs) grew substantially.4 While temporary supply chain disruptions during COVID-19 did increase input costs, many manufacturers maintained high prices even after supply chains recovered. New tariffs have introduced new pricing pressure for manufacturers, distributors, and retailers. Even sellers that are not exposed to tariffs are strategically raising prices, since they expect less individual blowback from consumers experiencing high prices across all categories of their purchases.5

In many cases, states already have laws on the books they could use to provide relief. For example, regulators of specific sectors, like utilities and insurance, already had the power to protect against monopolistic price increases. Others passed laws to directly block junk fees that push up prices when a consumer is captive or “provide” a worthless service that a consumer does not want.6 California launched an effort to secure a reliable supply of insulin, which would be distributed at-cost to pharmacies that agree to cap their profit margin. Each of these approaches is likely to bring relief to the cost-of-living crisis faster than simply relying on subsidies.

Iterations of the idea

Reboot State Regulators

Too often, state policymakers have allowed lesser known state agencies to operate with little scrutiny even when residents and businesses are struggling. In reality, these state agencies—usually regulating a particular economic sector—have specific licensing, registration, and pricing oversight responsibilities that they have broad power to administer pursuant to state statutes. For example, state regulators are typically required to sign off on price increases for electricity and gas utilities. Other agencies are charged with licensing firms that offer financial products and services, to which consumers routinely report anticompetitive rates and fees. In the case of state insurance commissioners, these regulators adjudicate applications for rate hikes on insurance products, including from companies that offer auto, property, and health insurance.

There are many other examples, including state higher education agencies, which oversee private colleges and universities and can review planned tuition increases, and state health agencies, which sometimes have power to block mergers of regional hospitals and acquisitions of physicians’ practices that would drive prices up.71 Depending on the state, these regulators can block private sector firms from price increases or even demand reductions. Some can even give consumers the ability to switch service providers more easily.8

But in many states across the country, state regulators typically acquiesce to price increases without robust analysis or public input. State policymakers must reboot these state regulators to find ways to lower costs for families, rather than simply serving as a rubber-stamp. In ten states, public utility commissioners are directly elected; after six rate increases over two years, Georgia voters defeated both incumbent commissioners on the statewide ballot, rebooting the regulatory body themselves.

Charter a New Competitor

State policymakers know that public infrastructure is essential for economic development. While we typically think about this infrastructure as physical (like roads and bridges) or human (like schools and colleges), states have a history of providing public infrastructure to support economic activity and lower prices. A public entity can serve as an important catalyst.

We have seen this in action at different times in history. In 1919, frustrated by how moneyed interests in New York were treating local banks and farmers, North Dakota chartered the Bank of North Dakota. Rather than compete with local banks, the Bank of North Dakota provides infrastructure and support for private sector local banks to meet the credit needs of the communities they serve. By participating in loans and offering liquidity for local banks, this state bank reduces costs for both local banks and for borrowers.

Importantly, states do not need to, nor should they, compete at every step of the process. States can intervene at particular stages, like financing, manufacturing, distribution, or even retail, where they see a failure. Small businesses have faced more serious challenges with rising input costs, since they are often dependent on a narrow set of suppliers. States should engage small businesses to understand where they face rising costs and excessive price hikes on essential inputs. Since many of these small businesses would benefit from obtaining reliable access to affordable supplies, states can determine whether existing agencies have the ability to supply inputs that lead to lower prices. This is especially important when parts of the supply chain have been hijacked or monopolized by entrenched incumbents.

States may not even need to charter a new corporate entity or public enterprise. In certain sectors, such as health care and higher education, legal authorities already exist to procure goods and services to meet a public mission.

(Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Case study: California’s CalRX insulin program Just recently, California chartered a public competitor to distribute insulin. Insulin has long been dominated by three companies that have repeatedly raised prices. According to some estimates, the cost to produce a vial of insulin is less than $5, but insulin makers have been charging up to $700 per vial9—which drives up health insurance costs even if it is not passed in full to the consumer.

The new CalRx program will partner with two manufacturers to produce insulin pens. Pharmacies can participate in the program by obtaining an affordable supply of insulin pens for their patients. Under this program, pharmacies are still allowed to mark up the insulin pens, but up to a maximum cost to patients of $11 per pen.

The pharmaceutical nonprofit Civica, one of the suppliers for CalRx, points out the program will be much simpler to navigate than other discounted insulin offerings, with no rebates, no coupons, no program to enroll in to get the CalRx price.10

Establish Price Protections

The United States has long been accustomed to policy that sets price floors or targets. The Federal Reserve Board’s Federal Open Market Committee meets every six weeks to adjust the price and supply of money. Congress authorizes the U.S. Department of Agriculture to ensure that certain crops command minimum prices in the marketplace. The U.S. Department of Energy holds a Strategic Petroleum Reserve, a stockpile of crude oil, where supply can be released into global markets to protect against price spikes.

As mentioned above, states are responsible for ensuring that critical industries that are not subject to normal competition are scrutinized for the prices they charge the public. Increasingly, states are finding that anticompetitive fees, markups, and prices have plagued many sectors of the economy.

Take the example of mysterious junk fees. Patients across the country now see “facility fees” pop up in unexpected places in health care, including for visiting an outpatient clinic or doctor’s office. This has caused confusion and hardship, even for patients with insurance. Eleven states have enacted or seriously considered reforms, with several banning facility fees altogether for many health care settings.

In some cases, price protections can help states prevent problematic practices and price gouging. Almost all states have statutes with some type of limit on interest rates charged for consumer loans. In the last decade, ballot measures have imposed greater limits. South Dakota enacted a new limit with 76 percent of voters in support, and Nebraska’s ballot initiative received support from 83 percent of voters.

Typically, the best state intervention for a cap on fees, markups, or prices is when the ordinary forces of competition cannot address high costs or limit profiteering in the short term. Limitations can also be time-limited, depending on the nature of the market failure.

For example, many states suffer from very high broadband costs. While new competitors can enter, they can’t enter quickly. Many states are exploring whether they might expand upon New York’s requirement that larger internet service providers must offer a plan as low as $15 per month to lower-income households.

States will need to look closely at the sectors of their economy where consumers and businesses are suffering from high prices, but where meaningful competition can’t drive down prices quickly.

Importantly, these tools can be used individually or in combination with one another to de-gouge sectors of the economy that have seen astronomical price increases and profiteering.

Here’s a few examples of how state policymakers can use these approaches to lower prices on key goods and services:

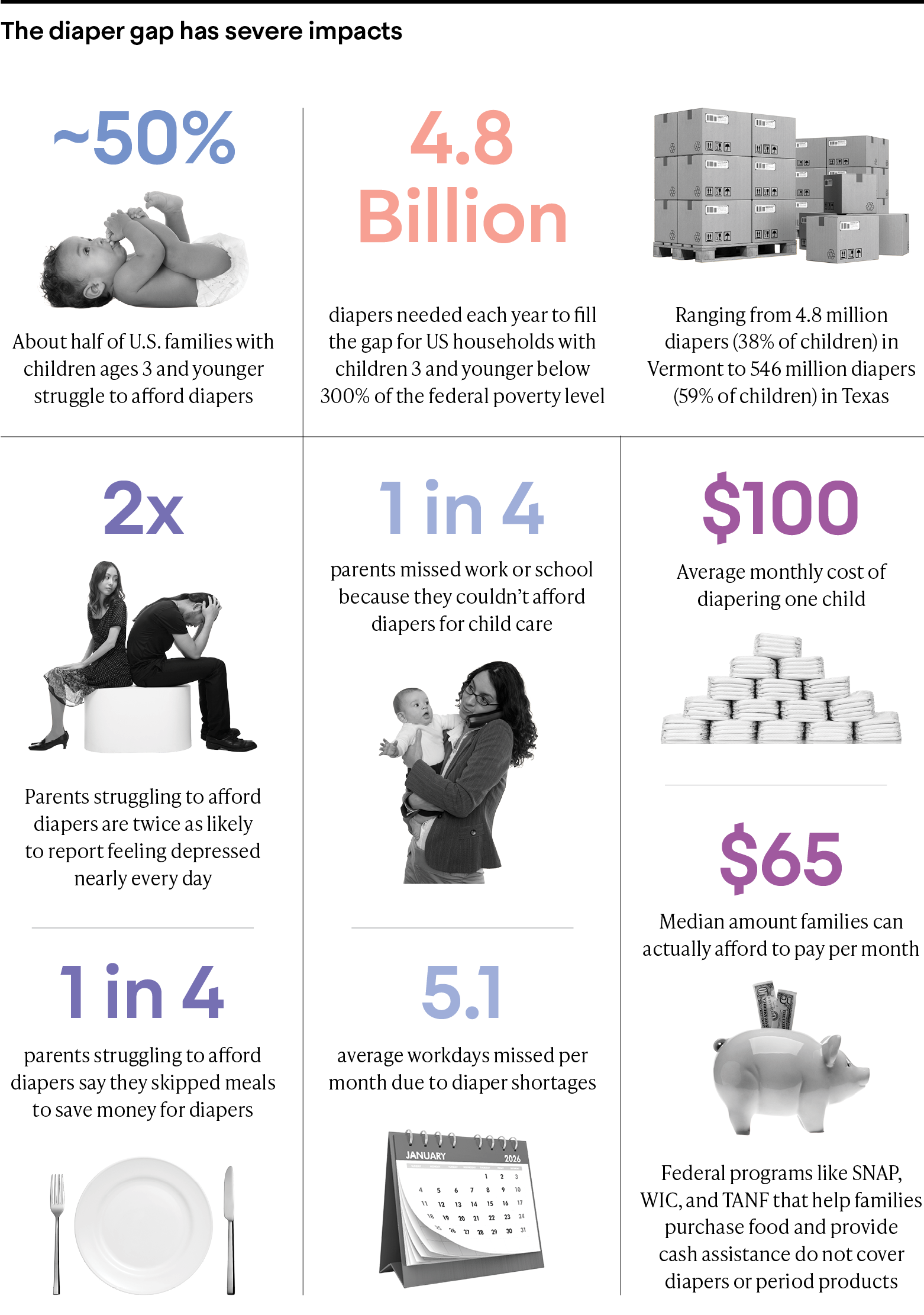

- Create a Strategic Diaper Reserve

According to the National Diaper Bank Network, roughly half of families with young children struggle to afford diapers. While many families with children are eligible for assistance for food, the spiraling cost of diapers has been a major source of stress for parents. Since the pandemic, the cost of diapers has increased by approximately 48 percent. While it was true that input costs for diapers went up, the dominant paper product conglomerates were also able to increase their profits given the little competition they face in the market. Other essential baby products such as formula have also seen steep price increases, which has led some families to make difficult sacrifices.States have a strong interest in stopping price gouging in markets for baby products. One way of reducing the likelihood of gouging is to develop a state stockpile of essential baby products. States could strategically procure critical supplies at competitive rates from manufacturers. When retail prices for these supplies exceed an affordability benchmark set by the state, the stockpile could release inventory to retailers for resale to consumers at reasonable rates.

Like other strategic reserves for minerals, oil, and food, a stockpile of baby products would also serve to protect against shortages and other disruptions that can sometimes create panic buying by parents fearing a lack of supply.

Urban Institute, Closing the Gap on Diaper Insecurity in the US, September 9, 2025. Photo elements: lostinbids, scanrail, elkor, keithferrisphoto, Laboko, studiocasper, spawns, clu (iStock)

- Lower the Cost of Insurance by Reducing Corporate Waste

State laws require insurance regulators to closely scrutinize the premiums charged by insurance companies, including for auto insurance, property insurance, health insurance, workers compensation insurance, business liability insurance, and renters insurance. Typically, rates are approved when insurance companies can demonstrate they cover the expected costs of administering and paying out claims, as well as a reasonable profit. Unfortunately, this disincentivizes insurance companies from being efficient, since they can pass back wasteful spending onto ratepayers and even earn a higher profit for doing so.State policymakers have already identified wasteful spending by regulated entities where costs are passed on to consumers. For example, some regulated entities expend resources on luxury private jets, massive advertising campaigns, and lobbying and political contributions. State lawmakers can enact policies that exclude certain types of expenses from being considered in the rate-setting process, unless the company can show that the expense leads to public benefits.

- Reduce the Price of Drugs through a State Pharmacy Benefits Manager

Many Americans lack affordable access to prescription drugs, especially those who need drugs not covered by insurance. States often have authorities to reduce this hardship.Pharmacy benefits managers are companies that serve as middlemen between pharmacies, drug companies, and patients. While drugmakers have been accused of exploiting patients, the pharmacy benefits managers industry has also been plagued by allegations of improper kickbacks and collusion, harming patients and independent pharmacies alike

States have already started to enact legislation to improve transparency, and some have established a single pharmacy benefits manager to reduce costs for state-administered Medicaid programs and for state employee and retiree benefits. These efforts also seek to ensure that any rebates benefit the public, patients, and pharmacists, rather than middlemen.

States can leverage the state pharmacy benefits manager to provide competitive pricing that could be made available to all state residents, including for private insurance plans approved by state regulators. Such an arrangement could give more bargaining leverage for state residents and dramatically cut costs for patients who would otherwise pay hyperinflated rates. In addition, it would address concerns about popular drug discount programs misusing sensitive health data, including by selling data to major tech companies for targeted advertising.11

State policymakers should closely audit existing grants of authority to state agencies and related entities to identify dormant authorities to better utilize state regulators, charter a competitor, and establish price protections.

Why act?

State policymakers often face two major constraints when seeking to help families make ends meet: budgeting and legislating. However, the policies using the framework above don’t require annual subsidies from state budgets. Even better, many states already have existing statutes that agencies can use to lower costs.

Take health care spending. Many states must already manage the costs for beneficiaries of Medicaid and other state-administered health programs. The strategies described above can help reduce expenditures for their state program and lower costs for consumers and patients outside of the program.

Or consider property insurance. States already have legal authority to approve and deny rate increases. Many states already have a state-administered property insurance plan. It’s critical they find ways to reduce costs to help control public spending and provide relief to ratepayers.

Incumbents often wield significant power over the market and within the political system. Many of these corporate players are direct beneficiaries of—and even contributors to—today’s cost-of-living crisis. Shining a light on the issue can help balance the scales in this power dynamic.

Small and medium-sized businesses need the help, too. Even though there will be pushback from entrenched special interests, many others in the business community, especially small businesses, have much to gain from state action. For example, many independent pharmacists strongly support efforts to address concerns with pharmacy benefits managers. Many regional businesses are sharing similar struggles as families to deal with the high cost of insurance. Franchised businesses suffer from price-gouging by franchisor-affiliated vendors. A wide range of businesses face severe challenges to address the rising cost of energy and utilities. When identifying a cost-of-living concern, state policymakers should determine where businesses face similar challenges to broaden the constituency for reform and the economic benefits to the state.

Point out historic precedents and bipartisan support. As noted above, state and federal policy has long sought to support economic growth and price stability in banking, agriculture, and so many other sectors. However, those advancing these policies need to be prepared for pushback from entrenched special interests, including accusations of “government takeover.” In reality, these policies typically work alongside and encourage private market competition. When legislative efforts also yield meaningful benefits for small businesses, they have also been bipartisan. For example, states like Kentucky and Louisiana have enacted bipartisan reforms on pharmacy benefit managers. Several states have taken action to protect small businesses from excessive fees.

Near-term economic security and growth are job one. When addressing these concerns, state leaders need to clearly communicate how these high costs are creating problems for economic security and growth, and for making ends meet each month. Americans are tired of hearing about so-called solutions that don’t seem to help them in the near term. But taking steps to de-gouge the economy in the short term is something that the public is ready to support. And policies to specifically ban outrageous fees would have support from broad swaths of the public.

End Notes

- While outside the scope of this chapter, the decision by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors to dramatically increase the size of its balance sheet in response to COVID-19 clearly had a significant impact on asset prices, including real estate, equities, and fixed income. Even while there was less income inequality, wealth inequality dramatically increased, as those with assets benefitted significantly from the intervention.

- Highlights From the Profile of Home Buyers and Sellers. National Association of REALTORS®, 4 Nov. 2025, https://www.nar.realtor/research-and-statistics/research-reports/highlights-from-the-profile-of-home-buyers-and-sellers

- Jones, Hannah. “Is 30% Rule Impossible in 2025? 47 of the 50 Largest U.S. Metros Now Require More.” Realtor.com Research, 25 Jun. 2025, https://www.realtor.com/research/may-2025-affordability-benchmark/

- Marto, Ricardo. “What’s Driving the Surge in U.S. Corporate Profits?” On the Economy, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 21 Apr. 2025, https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2025/apr/whats-driving-surge-us-corporate-profits

- Peck, Emily, and Courtenay Brown. “Businesses Are Raising Prices After Tariffs — Even on Unaffected Goods.” Axios, 4 June 2025, https://www.axios.com/2025/06/04/trump-tariffs-prices

- Chopra, Rohit. “Why States Must End Junk-Fee Creep”, The States Forum Journal, July 2025, https://www.statesforum.org/journal/issue-1/why-states-must-end-junk-fee-creep/

- Cooper, Zack, et al. Are Hospital Acquisitions of Physician Practices Anticompetitive? NBER Working Paper Series no. 34039, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w34039/w34039.pdf

- The Telecommunications Act of 1996 required mobile carriers to allow subscribers to keep their phone number, which reduced hurdles for switching and benefitted consumers. For example, some state agencies can require regulated entities to facilitate more seamless product or service switching.

- A lawsuit filed by the University of Pennsylvania outlines some of these concerns.

- Hwang, Kristen, and Ana B. Ibarra. “Gavin Newsom Launches Affordable Insulin for California Diabetics.” CalMatters, 16 Oct. 2025, https://calmatters.org/health/2025/10/insulin-california-announcement/

- Federal Trade Commission. “FTC Enforcement Action to Bar GoodRx from Sharing Consumers’ Sensitive Health Info for Advertising.” Federal Trade Commission, 1 Feb. 2023, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/02/ftc-enforcement-action-bar-goodrx-sharing-consumers-sensitive-health-info-advertising